Edinburgh art reviews: Muirhead Bone | John Keane | Orson Welles | John Bellany | Victoria Crowe

Muirhead Bone Collection, Summerhall, Edinburgh ***

John Keane: Life During Wartime, Summerhall, Edinburgh ****

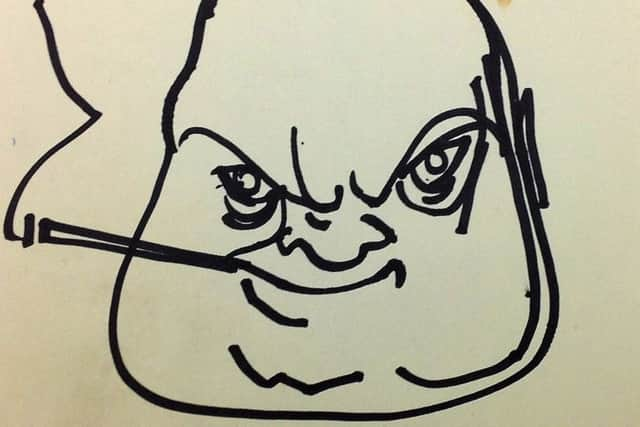

The Drawings and Paintings of Orson Welles, Summerhall, Edinburgh ***

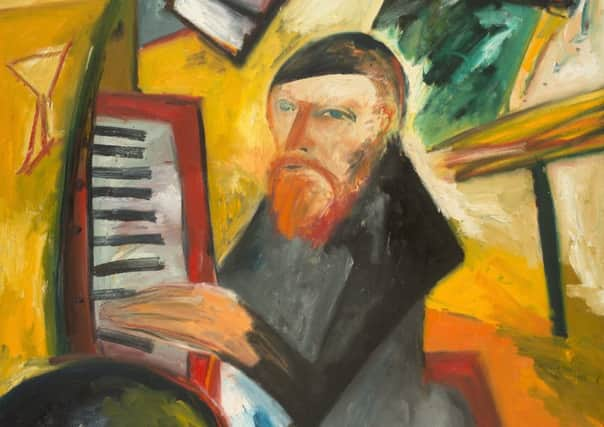

John Bellany: The Wild Days, Open Eye, Edinburgh *****

Victoria Crowe: A Certain Light, Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh *****

Advertisement

Hide AdThis is the centenary of the end of the Great War, a war so awful that the only thing that could make its memory bearable was the belief that it was the War to End All Wars. Sadly that belief was misplaced. Human nature did not change and now we look back across an intervening century of constant wars, great and small.

In that time, too, art and war have had an uneasy relationship. In 1916 Muirhead Bone was appointed as Britain’s first official war artist. His Western Front lithographs are on display at Summerhall. They seem at first low-key, but Bone’s job was not to be a Goya. He was an official artist. What he did do, however, was reject the heroics and misplaced glamour that had been the principal iconography of war hitherto, but the reality was perhaps also too dreadful to portray directly. He seems to have felt able only to record the violation of the landscape itself, its terrible denaturing, rather than the violence that brought it about.

When you compare Bone’s drawings to Goya, or the shrill horror of the war images of Otto Dix, for instance, his restraint may seem faint-hearted, but really it is a way of conveying the grim, enduring, human consequences of war, rather than its drama.

John Keane is also showing at Summerhall. He too has been a war artist and he too is generally restrained in his responses, focussing on the human cost of war, and indeed also of its offshoot, terrorism, rather than the immediate drama. Indeed, aptly, in pictures of the people caught up in the Dubrovka theatre siege in Moscow in 2002, it is literally the audience, the hostages seated in the theatre as though still at a play, who are the drama.

Keane’s pictures here range in date from 1991 and the first Gulf War to, rather surprisingly on the printed sheet of titles at least, 2019. Technically these works are mostly painted, but he also uses inkjet printed photographs which he then paints over.

The effect blends the neutrality of photography with the tactile directness of painting in a way that is reminiscent of Rauschenberg’s use of newsprint images.

Advertisement

Hide AdMine, described as “oil and inkjet on jute”, is a good example. It is a picture of an African woman seen from behind carrying two children across a landscape burnt black by fire. It represents perhaps “mine” as in the woman’s children, “mine” as in her property – was this desolation once her livelihood? – and “mine” as in is this desolate landscape also “mined”? We do not know which, but her courage is clear.

Another eloquent work here, If You Knew Me/If You Knew Yourself, is a life-size collage of a woman’s costume, but the woman herself is lost in blackness.

Advertisement

Hide AdThroughout, Keane’s responses to his subject matter are diverse. Alien Landscape from 1991, for instance, is arranged like an altarpiece with subsidiary scenes of war around a central landscape. There are vapour trails in a blue sky and the central scene is framed with US and Kuwaiti dollars and the whole thing with pages from a book.

In Distillation of Terror, Keane’s need for restraint in dealing with something as horrific as an Isis public execution reduces his image to interlocking rectangles of flat colour, yellow for sand, orange for a hostage’s jumpsuit and black for his Isis murderer. Muirhead Bone would have understood.

While you are at Summerhall, the drawings of Orson Welles make a surprising exhibition, a first apparently, though of interest more for its author than the art he produced. His Christmas cards, mostly of Father Christmas, occasionally drunk, were his principal artistic endeavour, but he was not a bad artist at all. There are quite competent adolescent drawings and others relating to his films and stage plays clearly have documentary interest.

Across town at the Open Eye, John Bellany was certainly not a war artist, unless you count the war he waged with himself for much of his life. This show brings together a really striking group of his work from the early 80s, a period of near meltdown for the artist. His marriage had broken down, his second wife Juliet committed suicide and he himself was well on the way to doing the same with drink.

Unsurprisingly, reflecting this, his painting from these years sometimes verges on the chaotic, but by judicious selection and careful hanging this show reveals how powerful an artist he could be even in extremis.

His astonishing draughtsmanship, the key to his achievement, clearly never wavered. A drawing here, for instance, titled the Skate Man Cometh, dated 1983, and for all its summariness a recognisable self-portrait with the familiar haunting fish, is defined by a few sweeping lines of charcoal with an assurance worthy of Matisse. There are other drawings with the same command and watercolours too. Beautifully painted, Bounteous Sea, for instance, seems to be a self-portrait with a paintbrush for a head.

Advertisement

Hide AdBut this is not simply a show of drawings, watercolours or small works. Far from it. One room is dominated by an explosive triptych, nine feet across, called The Skate Odyssey. The central panel is a gigantic, eviscerated fish. The birds that are the artist’s other sinister familiars are in the panels on either side. All are barely legible in the storm of his brush. The tension is palpable as he skirts the abyss of incoherence, but steering so close to danger only adds to the power of this remarkable work. Equally impressive is Mizpah, a big painting of the single figure of a cockerel perched on the prow of a fishing boat against a light sky and with written beneath it, “Mizpah”, the biblical name of an Eyemouth fishing boat. In its simplicity, the picture has a defiant, almost tragic grandeur. Fair Maid of Perth nearby is similar in composition, scale and impact. Altogether this is a remarkable group of works.

Victoria Crowe is also a master draughtsman and she currently has two major shows. As well as an exhibition of her portraits at the SNPG (see Scotsman.com for our review), she is now also showing at the Scottish Gallery. The show’s title, A Certain Light, reflects a preoccupation with light, not so much simple daylight as the crepuscular moment between light and dark. She paints trees in evening light and Venice, too, in similar mood. She also paints flowers, not as simple still life, but in pictures in which the complexity of the light makes them openings on to a landscape of reflection. This is a truly poetic show. An antidote to John Keane’s war and Bellany’s angst, but rich and serious painting all the same.

Muirhead Bone, John Keane and Orson Welles until 23 September; John Bellany until 27 August; Victoria Crowe until 1 September