Art reviews: The German Revolution at the Hunterian | Rosalind Lawless & Hetty Haxworth at Glasgow Print Studio

The German Revolution: Expressionst Prints, The Hunterian, Glasgow *****

Rosalind Lawless and Hetty Haxworth: New Work, Glasgow Print Studio ****

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe first decades of the last century saw revolutions in painting and music. In Britain, however, with a few brave exceptions – JD Fergusson in Scotland, or Wyndham Lewis in England, for instance – the response to new ideas was cautious at best. The status quo held. In England, at least, revolution was for foreigners. In the Kaiser’s Germany, as in the Czar’s Russia, however, the response to new ideas was at once artistic and deeply political. Indeed, as events unfolded, it was, to an extent, the passion of politics manifest in their art that earned the artists their name “expressionists.” If art and politics were inextricably intertwined, however, nice paintings in bourgeois drawing rooms were never going to make a revolution. But prints and graphic magazines were different. They were cheap and could circulate. In Germany they became the artists’ favoured medium and are now the subject of The German Revolution: Expressionist Prints at the Hunterian, marking the centenary of the failed German revolution of 1919.

The show is drawn largely from the Hunterian’s own great collection of prints. That in itself is remarkable. It was pretty well unthinkable to buy or even consider German art after the end of either war. In 1950, however, the Society of Scottish Artists courageously pioneered reconciliation with a show of German expressionist art which included Max Beckmann, Emile Nolde, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Max Pechstein and others in this present exhibition. Then in Glasgow, Andrew McLaren Young began to buy German prints for the Hunterian. Later, Douglas Hall bought for the National Gallery of Scotland Max Beckmann’s print series Hell, made in 1919. Thirty-two years after the SSA’s initiative, the purchase still seemed bold although Beckmann had become topical because of his influence on John Bellany. This dramatic series of 12 large lithographs is one of several important loans to the Hunterian show.

The young German radicals consciously looked back to the Renaissance printmakers Dürer and Schongauer, and so they are represented here. A print from Goya’s Disasters of War demonstrates how powerful his example was for artists faced with the horror of the trenches. A late 19th century etching by Franz von Stuck of a naked woman embracing an enormous serpent anticipates the sexual ambivalence and anxiety that these artists frequently expressed, reflecting, as Freud did at the same time, the personal side of a revolution in ideas and behaviour.

Gauguin was also a key figure. His vision of a paradise of sexual liberation, represented here by a single print, led at least two of these artists, Emile Nolde and Erich Heckel, to follow him to the South Seas. A woodcut by Heckl is a wistful erotic dream of two naked women on a Polynesian beach. Nolde has a very different print of women in a storm, but also Scribes, a horrid piece of anti-Semitic caricature. (Nolde joined the Nazi party early on and, though they rejected him, he remained a member throughout the war. The division between left and right was not straightforward.)

Edvard Munch worked in Berlin for a number of years and was also part of this story. Sex, though melancholy, not liberated, joyful, or even wistful, was his constant theme too. It is illustrated here, quite literally, in a woodcut of a man with a naked woman swimming through his head in an expanded thought balloon. Technically Munch’s way of using woodcut showing the grain and texture of the wood was widely influential. You see it in Max Pechstein’s In the Water, a rather simpler variation of Munch’s favourite theme, as a young man falls back overawed by a naked girl rising out of the water, and also in his strange print of the One-Eyed Mother. (Representing people full-face with one eye was an anti-classical trope with a long history.)

Picasso was of course the undisputed leader of the revolution in art and his Cubist dislocation of space provided the framework without which expressionism might simply dissolved into incoherence. Beckmann’s Hell series, a 12-part vision of urban dystopia with the artist as witness, is an essay in cubism as an expressionist vehicle, although its ultimate inspiration was Hogarth.

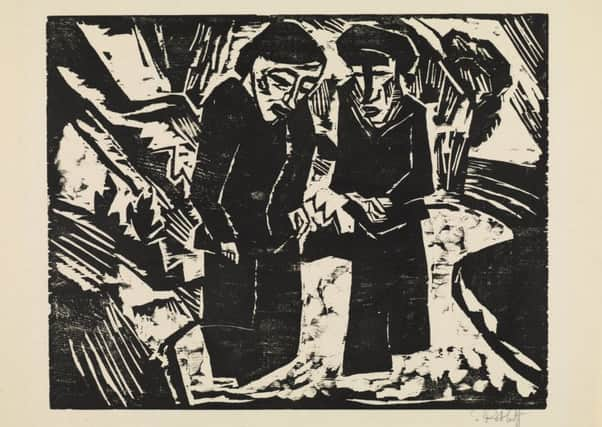

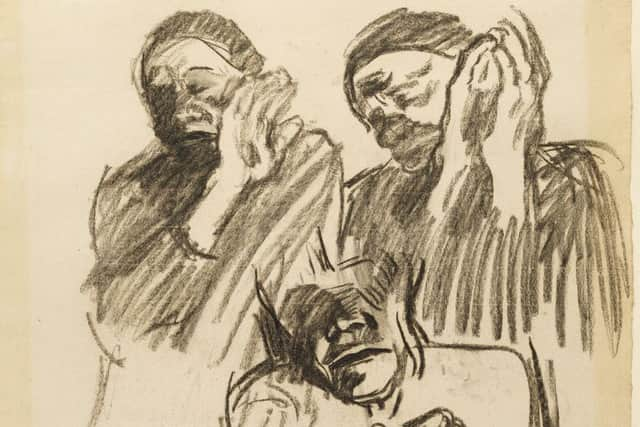

Before Cubism, too, Picasso’s example was important. It is wonderful to see his beautiful, early etching, The Frugal Meal, and nearby Egon Schiele’s magnificent drypoint, Sorrow, a woman crouching, head bowed, which echoes Picasso’s print directly. Schiele’s forms are cubist, however, and the tautness of his composition shows how expressionism is a language of control, not abandon: how it depends on the tension of navigating the giddy edge of chaos without slipping into dissolution. We see the same thing in Beckmann’s Adam and Eve, also in drypoint, and in Otto Dix’s print of Acrobats. George Grosz’s Attack is a lithograph of a bomb exploding in a crowded street. The composition literally explodes, but a jigsaw puzzle of cubist drawing keeps it coherent, if only just. The jagged lines and brutal simplification of roughly-handled woodcut are held together by the same visual logic in Karl Schmidt Rottluff’s Mourning Women on the Beach, for instance, or in his Man and Wife.

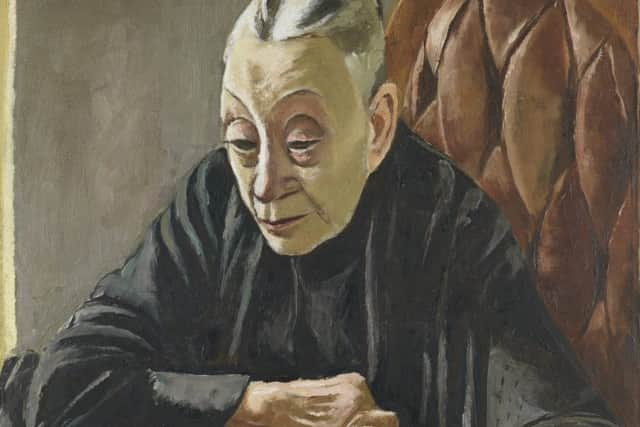

As early as 1901, Kathe Kollwitz made La Carmagnole. An image of revolution in the raw, it is a large etching of women dancing barefoot around a guillotine to the beating of a drum. There is blood flowing from the foot of the guillotine and La Carmagnole was a French revolutionary song. The medieval streets beyond the guillotine show this is Germany, however, a country still stuck in the past. Led by the women, the people are about to break free. Kollwitz also describes the oppression and suffering against which she hoped to inspire revolt in such images as Working Woman in Profile, just the weary face and powerful hands of a woman seen against darkness, or in a wonderful drawing of a woman and child. Kollwitz was a true radical and a great pioneer printmaker. It is fitting that she has the last word here with the latest work in the show, a self-portrait in profile made around 1938. Condemned by the Nazis and banned from exhibiting, in 1936 she and her husband were threatened by the Gestapo with deportation to a concentration camp, but she lived on through the horror of war to die just days before its end. Stark, implacable and defiant, untouched by any hint of self-pity, her self-portrait speaks at once of her indomitable strength and the bitterness of a life that went from dreams of revolution to Nazi persecution. It is surely one of the greatest witnesses of its time as indeed was she.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMeanwhile at Glasgow Print Studio, two contemporary printmakers, Rosalind Lawless and Hetty Haxworth, seem very decorous in contrast to all this. As though the spirit of Philip Reeves still presides over the Print Studio, both artists explore the line between balance and instability in compositions of abstract shape and colour. Haxworth favours floating rectangular shapes using monotype to achieve a satisfying resolution occasionally reminiscent of Ben Nicholson. Lawless’s geometry is freer and her colour a little more intense, though the results are equally satisfying. Both artists also experiment with materials in intriguing ways, cutting out and collaging them to create compounds that manage to be at once image and object. - Duncan Macmillan

The German Revolution until 25 August; Rosalind Lawless and Hetty Haxworth until 31 March