Art reviews: Helen Flockhart | Rabiya Choudhry | Paul Noble & Patrick Geddes

Helen Flockhart: Linger Awhile, Arusha Gallery, Edinburgh ****

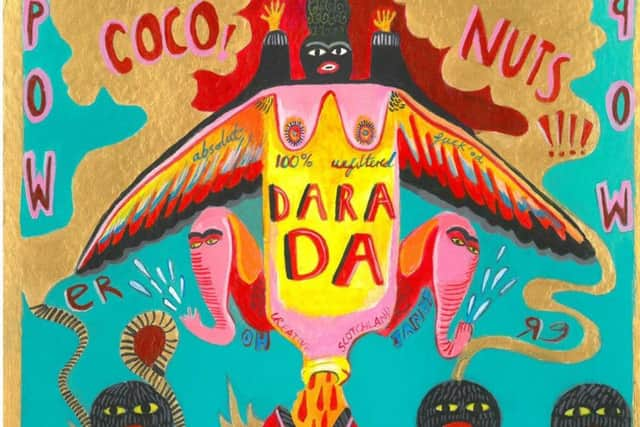

Rabiya Choudhry: COCO!NUTS!, Transmission, Glasgow ***

Paul Noble and Patrick Geddes: Politics of Small Places, Cooper Gallery, Dundee ****

Advertisement

Hide AdHad she been born in a different century, one feels Helen Flockhart might have been a miniature painter, fashioning keepsakes of secret lovers and lost children. While her strange, sad portraits and mythical vignettes belong almost entirely to our own time, her highly finished, immaculate style would not be out of place in an earlier age. Perhaps this is why, in her latest body of work which is inspired by Mary, Queen of Scots, she seems so perfectly at home.

The bloody, romantic fairytale of Mary’s life seems ideally suited to Flockhart’s style, her mysterious, sad-eyed souls adrift in circumstances beyond their control. Mary, of course, is one of them, a woman of royal birth who, on account of her gender and her youth, became a pawn in other people’s dramas, shunted from marriage to marriage, from country to country, spending the last 20 years of her life as a prisoner.

This major sequence of paintings will transfer to Linlithgow Burgh Halls from 12 October to 20 January, near the palace where Mary was born. Flockhart paints her in portrait after portrait, complex expressions flitting over her pale face. She stands against Rousseau-esque dense foliage, with backgrounds full of symbolism: a split fig, a peeled lemon, eyes which glint among the leaves and – in one painting – a hand which seems to reach for her from behind. Mary was always watched and, one suspects, always watching.

Flockhart also paints imagined scenes from her life. The title painting of the show has Mary and her first husband, the Dauphin of France, married when they were respectively 15 and 14, lying together in a bed strewn with flowers, wed but still in childhood innocence and – one guesses, one hopes – happiness. In Rizzio, the Queen’s friend/lover is painted as the god Pan, while Mary flies, carefree, on a swing, and menacing dogs gather in the bushes. In Suffer or strike, Mary, just before her execution, waits in a darkened room in front of a blazing fire, prefiguring the bonfire used to destroy her belongings to stop them becoming political props in the hands of her supporters.

Flockhart clothes her in symbolism, too, sometimes in period ruffs and gowns textured with tiny brushstrokes, sometimes in fabric on which is printed scenes from her life or lines from her writings. In O Elizabeth, her hair is down and she wears a loose wrap-around dress, suspended between her time and ours. Clothes display her grandeur and restrict her movement, a woman whose supposed royal power meant she had no freedom of her own.

Rabiya Choudhry is a very different painter, though she too weaves a rich seam of symbolism through her work. COCO!NUTS! is her first solo show, and an important chance to see a body of her work and tease out the disparate strands she brings together. Her work is comedic and poignant, personal and political, playful and serious, all at the same time. A graphic style, bold colours and visual jokes run through paintings which comment on war, mental health and personal loss.

Advertisement

Hide AdLike Flockhart’s work, the more you linger the more you see: symbols in the details, words and sentences woven into the paint. Images from contemporary culture, advertising and her Scots-Asian background are brought together to form a highly personal visual language.

Terrorvision shows a grinning bat-shape atop a pair of human legs, one hand clutching a passport, the other a paintbrush. Dream Baby Dream is a cross-section of a head, in which little bearded minion-like figures run departments for ears, eyes and mouths; the word “suicide” is spelled out on the jagged teeth. Prayers for Moona is full of love: “cancer returns” and “keep the faith” are written into the colours. Car Crash, January 25th is named for the day when a number of organisations, Tranmission included, lost their regular Creative Scotland funding.

Advertisement

Hide AdJust as Flockhart paints elements of Mary’s story on to the fabric of her dress, so Choudhry takes colourful motifs from her paintings and uses them to make a range of printed textiles, which are made into dresses, purses and ties, a small homage to the fashion shops her dad ran in Glasgow in the 1980s and 90s. It’s a promising show, and affirms Choudhry as a distinctive voice in Scottish art.

Turner Prize nominated artist Paul Noble has spent 15 years making detailed drawings of Nobson Newton, a fictional new town dystopia. At Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design’s Cooper Gallery, curator Sophia Hao makes an inspired pairing of his work with drawings by Patrick Geddes, 19th-century town planner, polymath and one-time resident of the city. As Dundee reflects on cities and design, in the spotlight of the newly opened V&A, it makes a quirky and profound addition to the discourse.

The major work here is Nest (2004), an eight-panel marquetry screen featuring an embroidered scene of futuristic housing units made from egg boxes and a dead tree. Eggs recur in Noble’s work, here in Black Egg and the film Eggface, so Noble and Hao were astonished to discover, in the Geddes archive held by Strathclyde University, a drawing titled The Earth as a Floating Egg.

It is included here along with seven other Geddes drawings which he refered to as “thinking machines” – mind maps, perhaps, a century before the term came into use. Drawn in blue and red crayon, they burst with energy and ideas as his erratic, polymathic mind grapples with the interconnectedness of economic and social systems, philosophy, religion, Kant and karma. “Life?” he writes at the top of one sheet. And “Life?” is his subject.

So the works, produced 150 years apart, sit together, Geddes’ energy-fuelled mind-maps and Noble’s immaculately realised drawings, the Victorian trying to make sense of the world and mould it into something better, and the 21st century artist who has seen the other end of too many failed utopias. Both reflect on the design of the city (Geddes invented the word “conurbation”) which continues to bring us the best and the worst of humanity and, like it or loathe it, dictates how the majority of us live. n

Helen Flockhart until 7 October; Rabiya Choudhry until 20 October; Paul Noble and Patrick Geddes until 6 October