2018: The Year in Visual Art

Stephen Campbell: Love

Tramway, Glasgow, January to March

The year began with Love, a show of Steven Campbell’s collages at Tramway. There were 12 of them, all made in a single period of work in the late 1980s. The collages had not been seen for 25 years and never before all together. They were the product of a profound personal crisis which nearly stopped Campbell making art. It was typical of him though, and of his belief in painting, that he sought to resolve this crisis in a self-conscious dialogue with the great masters, remaking his art from the ground up. The complexity of these collages and the sheer effort involved in making them were a measure of his determination to meet the challenge he had set himself. There are references to Matisse throughout, and he quotes from Picasso, Max Ernst, Mondrian and others among the greats of Modernism. Very few contemporary artists could conduct such a dialogue and not simply emerge looking diminished by the grandeur of the company they had chosen. He did, and from there went on from strength to strength until his untimely death in 2007, aged just 54. DM

NOW | Jenny Saville, Sara Barker, Christine Borland, Robin Rhode, Markus Schinwald, Catherine Street

Advertisement

Hide AdScottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, March to September

In the NOW exhibitions, the National Galleries of Scotland have developed a superb idea for showcasing contemporary art. Each show – there will be six over three years – centres on a significant body of work by one artist, and draws in others through a network of aesthetic or thematic connections. The result is a series of shows which introduce us to new artists as well as reminding us why familiar ones are important.

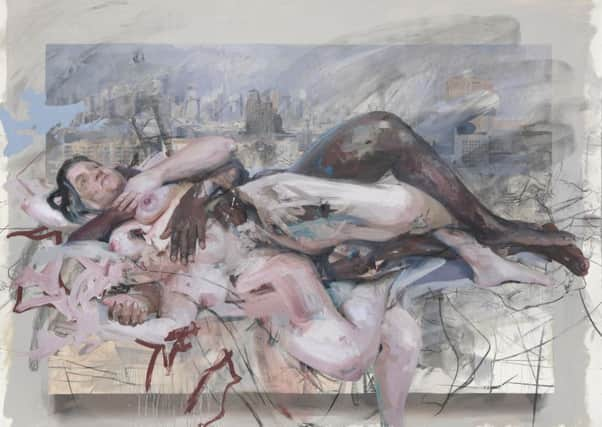

The third NOW exhibition featured a body of work by Jenny Saville, whose paintings have been little shown in Scotland since her degree show at GSA was bought by Charles Saatchi 26 years ago. It was a chance to see why she has been so celebrated, and how her work has developed in that time. The work in NOW spanned that quarter century from her degree show to Aleppo, a brand new work made in response to the Syrian refugee crisis, which hung between the Titians in the National Gallery of Scotland on the Mound. The scale of ambition was consistent throughout as was the revelling in physicality, both of paint and of the human body, but the exhibition also showed the new directions she has been exploring. SM

Charles Rennie Mackintosh: Making the Glasgow Style

Kelvingrove Museum, Glasgow, April to August

The celebrations planned for 2018 as the 150th anniversary of Mackintosh’s birth were blighted by the terrible fire which destroyed Glasgow School of Art’s Mackintosh Building in June. The fire came to overshadow the triumphant opening of the reconstructed “Mackintosh at the Willow” tea rooms on Sauchiehall Street, and this, Glasgow’s first Mackintosh exhibition for more than 20 years. Featuring more than 250 objects, it drew out fresh aspects of the man and his work. New light was also shed on his contemporaries, such as James Salmon Jnr, arguably the city’s finest Art Nouveau architect, many of whose buildings are now in a perilous state. SM

Christine Borland: To The Power of Twelve

Mount Stuart, Isle of Bute, June to November

Christine Borland’s Kelvingrove commission, funded by 14-18 Now and Glasgow Museums to mark the centenary of the Armistice, was unveiled in November, but her engagement with the First World War goes back much further, to work she made for the contemporary visual art programme at Mount Stuart in 2003. The opportunity to revisit the house this summer enabled a much more thorough exploration of the subject. The neo-gothic country retreat of the Marquesses of Bute was a naval hospital during the First World War, which gave Borland – interested in both history and medicine – plenty to work with. Always rigorous in her choice of materials, she filled the floor of the Marble Hall with a pool of globes made from medical-grade glass encircled in a cushion of sphagnum moss, harvested in Scotland and used in First World War hospitals as an antiseptic.

It was here, too, that she began her work with feeding cups, which would form the foundation of her work at Kelvingrove. Mount Stuart’s huge, polished dining room table became a museum of fragments, after 144 cups were blown to pieces by a bomb disposal unit in Belgium. The cup has a double-edged history, used in hospitals to help those unable to feed themselves, but also used to force-feed hunger-striking suffragettes. It became the potent lynchpin of a body of work which explores a difficult history about which we still have conflicting feelings. SM

Rembrandt: Britain’s Discovery of the Master

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, July to October

Advertisement

Hide AdTo do something like a Rembrandt show these days, you need an angle. The angle that the Scottish National Gallery chose for its big summer show was Rembrandt: Britain’s Discovery of the Master. It proved quite a good story and the show did also include a decent complement of Rembrandt’s own work, both paintings and etchings; he was one of the greatest ever printmakers. The star of the show was The Mill, once called “the greatest painting in the world.” It really does have such a presence it could have been an exhibition all on its own. Another star was An Old Woman Reading, a wonderful study of old age and also of light. It is a masterpiece of observation, but also spiritual. All sorts of artists good, bad and indifferent imitated, copied, learned from or forged Rembrandt and they were all there, a good story if not always good art. Some of the best who learned from Rembrandt though were Scots, notably here Wilkie and Thomas Duncan. It was poignant to see a beautiful painting of an old man, now in a collection in America, that once hung at Penicuik House and was most likely bought from Rembrandt himself by John Clerk of Penicuik. DM

Shilpa Gupta: For, in your tongue, I cannot hide

The Fire Station at Edinburgh College of Art, July and August

Advertisement

Hide AdOne of this year’s Edinburgh Art Festival commissions, For, in your tongue, I cannot hide, by Mumbai-based artist Shilpa Gupta, commemorated 100 poets who have been imprisoned, from the 8th century to the present day. Her installation made superb use of the disused fire station, creating a darkened space in which 100 rusted metal rods each speared a page on which a few lines of verse were written. Each also had a microphone from which voices brought these words to life in a carefully orchestrated vocal symphony. Some were overtly political, others spoke of universal themes: love, home, freedom, equality. From Peru in the 1920s to Nigeria in the 1990s and China last year, they were the words of artists, radicals, Nobel prizewinners. What struck me so strongly about this exhibition is how easily it could have gone wrong: become a babble of voices, impossible to distinguish, overwhelming. Gupta’s care and precision made it a powerful hymn to creativity in dark places, a timely reminder that creative people are often the first up against the wall. SM

Barbara Rae: The Northwest Passage

Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, August to September and Pier Arts Centre, Orkney, September to November

Sometimes a particular subject galvinises an artist, opening up a new seam of exploration from which riches pour forth. Barbara Rae’s voyages to the Northwest Passage inspired such an outpouring that the galleries of the RSA could barely contain them, a powerful response to a powerful and strange environment. Rae’s paintings are often informed by landscape, but in the past have more often drawn on the heat-drenched deserts of southern Spain and Arizona. The Arctic has opened up a new kind of palette: blues, greys and silver, illuminated by dramatic flashes of pink, orange or green. She captures the great towering walls of icebergs, alien vistas of ice floes stretching into the distance, and traces of human habitation. If you are an artist of long experience at the height of your powers, it takes courage to throw yourself into a new adventure. This vibrant body of work reminds us just how productive that can be. SM

Frances Walker: So Far...

Peacock Visual Art, Aberdeen, September to November

Frances Walker was a founder member of Peacock Printmakers in Aberdeen and has been a pillar of the organisation ever since. It has been a reciprocal relationship however. She has worked closely with the workshop’s skilled printmakers and has herself become outstanding in the field. A show of her prints from the last eight years in Peacock’s gallery demonstrated her mastery, but also that her work is still evolving. Indeed the show was titled Frances Walker: So Far... suggesting just that: she may have come a long way, but she is still travelling. The works included etchings, screenprints and lithographs. Several also combined techniques in original and inventive ways. There was work recording things she saw on the journey she made to the Antarctic a few years ago. There were also characteristic prints of rocky shorelines with rock pools. In these the quality of the etched line is really vivid, matching the geology she describes so well. There were also wide views, including one striking screenprint of the Sound of Sleat. She is a truly remarkable artist. DM

William Hunter: The Anatomy of the Modern Museum

The Hunterean, Glasgow, September until January 2019

The Hunterian bears the name of the great Scottish surgeon William Hunter, who bequeathed his remarkable collection to the University of Glasgow. 2018 is the tercentenary of Hunter’s birth and it was marked by a major exhibition on Hunter and his collection. Allan Ramsay’s superb portrait of his

friend was a key exhibit. Hunter’s beautiful painting by Chardin of a woman taking tea was also one of

Advertisement

Hide Adthe stars. It was not just a collection of art however. There were also drawings, engravings and indeed painted three dimensional models relating to his work as a surgeon and his magnum opus, the Human Gravid Uterus, published in 1774 and a masterpiece of medical illustration. He also studied animals in the interest of comparative anatomy and there were several paintings by George Stubbs. But Hunter’s ambition went beyond all this to create a universal museum. To this end he formed a magnificent library including very important early editions of classical texts, but also medieval illuminated manuscripts. He also collected what would now be called ethnography including artefacts and art works from the South Seas following Captain Cook’s expeditions. He formed one of the finest collections of classical coins and collected insects, geological specimens and much more, but it was not random. He was collecting at a time when it was still possible to hope to reach some kind of comprehensive grasp of the world and all that is in it. DM

Ocean Liners: Speed and Style

V&A Dundee, September until 24 February 2019

The V&A Dundee was launched with the major exhibition, Ocean Liners. Between the wars there was international competition in building great liners to race across the Atlantic to New York. These mighty ships were masterpieces of marine engineering. The exhibition showed off this side of the story with models and photographs of ships and engines, but the competition was not only about speed – it was also about glamour and luxury. The ships showed off decorative design at its most extravagant and luxurious and this was vividly brought home by a display some of the art works that decorated them. There was a life-size mock-up of a swimming pool and also actual outfits worn by very rich passengers. The exhibition gave us a picture of a lifestyle as lavish as any lived by the ancient Romans, but it was also short-lived. Beginning just before the First World War, it was over soon after the Second. Now we have budget airlines. DM