Kevin Byrne, who has lived and worked on the ten-mile-long, two-mile-wide Isle of Colonsay for the last 40 years, says he could always spot a newcomer in his days running the island hotel and bar.

“If they came in and answered the question ‘what brings you here’ with ‘I’ve come to get away from the rat race’ it was the kiss of death.

“The locals always used to say ‘if you can’t keep up with the rats you’ve come to the wrong place.’

“This isn’t a place where you can come and hope to do nothing and live off a few rabbits.”

Byrne is one of around 135 people who currently reside on the remote Inner Hebridean island of Colonsay, where the primary school has just eight students and crime is so rare that the community made national news in 1993 when it was reported that the last crime committed on the island was treachery against the King in 1623.

In spite of its modest size, Colonsay has an active, close-knit community and a surprisingly wide array of facilities.

Amongst other things, the island is home to a functioning 200-year-old golf course, a brewery and a bookshop run by Byrne and his wife Christa, plus a festival that brings visitors to the shores every spring.

“The community is quite close-knit, we tend to know and take an interest in what everybody else is doing - and with whom!

“By and large I regard it as benign and friendly though, and people pull together very well.”

To many, life on the white sand beaches and rugged cliffs of an island like Colonsay may seem an idyllic escape from the pressures of modern life, but Byrne stresses that self-sufficiency and forward planning are vitally important for survival.

“When I ran the hotel I always made sure there was enough drink for three weeks at the very minimum.

“Once there was an aeroplane crash nearby - a NATO plane - and for weeks there were foreign ships around the island doing a search.

"When they were done for the day all the men would come to the hotel bar for a drink - if I wasn’t in the habit of stocking three week’s worth of drink I’d have had nothing to give them!”

To outsiders, the success of Colonsay may come as a surprise. Decades of depopulation have created a general assumption among the wider public that the islands are dying out, stuffed with old people and propped up by a disproportionate share of mainland money.

However, with a recent upturn in population, an increasing need for green energy and growing distaste among many mainlanders for the pace of modern life, the opposite may be true.

Scotland’s remotest islands, home to unique heritage, communities spanning generations and some of the oldest rock formations on the planet, may finally be reversing their fortunes.

Islands then and now

The majority of the UK’s island territories are in Scotland, with around 790 scattered around the country.

They stretch all the way from Arran off the Ayrshire coast to Unst in the Shetland Islands - which is closer to the Norwegian city of Bergen than Edinburgh.

There’s strong evidence that people have lived on these islands for centuries, with Europe’s most complete Neolithic village Skara Brae sitting on Mainland island in Orkney.

Yet of these hundreds of islands, only an estimated 93 are inhabited today.

Following a growth during the Early Modern period, total island population began to decline in the mid-19th century, continuing on this track for decades.

One of the early catalysts for this was the Highland Clearances, which saw huge numbers of tenants forcibly evicted from their homes between 1750 and 1860.

Both Pabbay and Fuaigh Mòr in the Outer Hebrides were, for instance, left totally uninhabited after officials forced furious local populations to leave to make way for enclosed land and sheep.

Other islanders were killed off or forced to leave as a result of famine and disease.

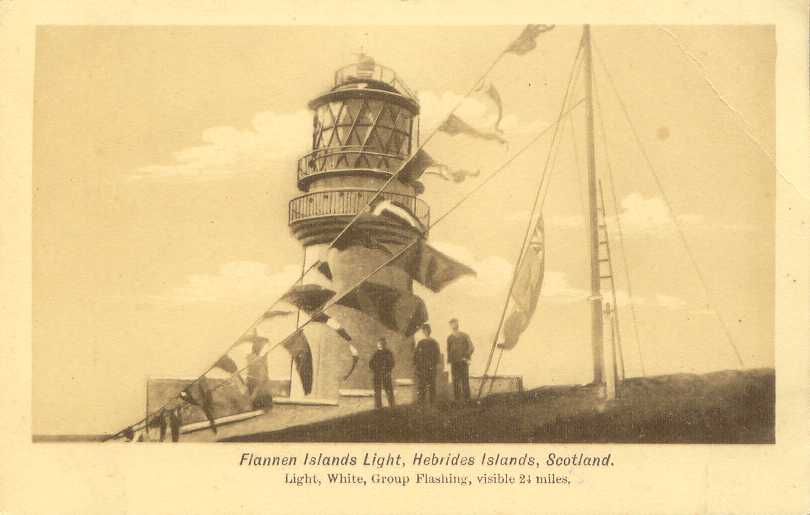

Some island abandonment has been more mysterious: the disappearance of three lighthouse workers from the Flannan Isles in 1900 remains a mystery to this day.

In more recent decades, starvation and disease have been replaced by job precariousness, food scarcity and challenging weather conditions as reasons for islanders to leave in droves.

In particular, the exodus of young people from Scotland’s islands presents a pressing challenge for the future, with a report from the James Hutton Institute estimating that working age population will plummet by a third in Scotland’s rural areas by 2046.

It’s feared that a decline could halt economic development and lead to more island communities dying out, taking centuries of culture and history with them.

Even when working-age people do resist the pull of opportunity in the cities, a lack of affordable housing threatens to price them out.

A 2019 survey found that this demographic were struggling to afford a life on the Scottish islands, blaming platforms like Airbnb for steep increases in housing costs.

'Islands have their own unique heritage'

Scotland’s 2011 census was, however, a glimmer of hope for the islands - at least on the population front.

Bucking a trend of decline that had seen three per cent of the islands’ total population leave between 1991 and 2001, between 2001 and 2011 the population grew by four per cent.

Colonsay’s own population increased from 108 to 124, and the island has gained at least 10 more permanent residents since.

This increase can be attributed to a number of factors, not least the efforts from local people and governments to encourage tourism and immigration to the islands.

A tour of Scotland's abandoned islands

In 2017 the “Islands Bill” was introduced into the Scottish Parliament with the aim of making sure the most remote of Scottish islands would be properly accounted for in future policy-making decisions.

Islands Minister Paul Wheelhouse claims that, among other issues, the perception of islands as somewhat primitive is something that needs to be addressed by the bill.

“The Islands Act 2018 recognises our islanders are talented and full of entrepreneurial spirit but it also recognises there are challenges - not least around perceptions of remoteness.

“Our islands have their own unique heritage, landscapes and marine biodiversity so we need to maintain and enhance these valued assets.”

Following this, in April this year the Scottish Government released a set of consultation questions which they urged islanders to answer.

The purpose of the consultation is to create a plan to “set out how the Scottish Government, local authorities and other public agencies might work to improve outcomes for island communities”.

It seems likely that the responses will echo the formula that other islands have utilised for success: putting the management of island affairs back into the hands of the islanders, investing in the right places and launching campaigns to encourage tourism and immigration to the islands.

The buyout of Eigg in 1997, for instance, led to more affordable housing being built on the island and population creeping above 100 in 2017 for the first time in half a century.

Not long afterwards, the nearby island of Ulva launched a similar campaign and won their buyout in 2018. Other islands, like Stronsay, have launched campaigns with the support of tourism groups to market their island as the ultimate getaway from the hustle and bustle of ordinary life.

In some areas this approach seems to be working. Tourism to the 23 inhabited islands in the Argyll and Isles saw an increase in 2017 after falling to the lowest recorded levels in recent years during 2016.

This boost can also likely be attributed to a growing appetite - among younger people especially - for an “off-grid” life.

The “#vanlife” hashtag, used by those who have given up ordinary homes to travel in a van, has been used more than 5 million times on Instagram, while a 2015 survey from Kellogs found that three-quarters of Britons reported being “fed up with modern life.”

If these trends continue the islands may benefit from new, younger residents to balance out ageing populations.

Climate threats - and solutions

While depopulation may be a pressing concern for Scottish islands, it isn’t the only one.

In recent years, climate change has brought a sharp increase in rainfall to Scotland as a whole, making weather conditions significantly worse for islanders today than the generations before them.

Changes in temperature have also brought invasive species like rats to the shores of islands like Colonsay, making life more difficult for residents.

Worse still, some islands may be at risk of literally disappearing as coastal erosion slowly wears away the landscape.

In 2017, the Dynamic Coast Project found that almost a fifth of Scotland’s coast is under threat of erosion in the coming decades, putting historic island heritage sights like Skara Brae at risk of destruction.

Yet while the islands are certainly at risk from climate change, they’re also key players in the fight against it.

The Orkney archipelago of about 20 populated islands is leading the way when it comes to sustainable energy.

They’re currently producing so much, in fact, that they can’t find enough uses for it, with an average of 120% above the islands’ needs produced each year.

On these islands, the high winds that have inconvenienced islanders for generations have now been harnessed to power wind turbines for clean energy.

Many residents drive electric cars, live in homes powered by wind, and are pushing for the island ferries to switch out diesel for hydroelectric power.

Wind power is the fastest-growing renewable technology in Scotland, and aside from the clear environmental benefits, deploying it on island communities could mean more jobs and a boost to struggling economies.

Scottish islands are also home to an extremely broad range of biodiversity, a fact that Kevin Byrne believes will place them front and centre of policy decisions and public life in the future, especially after Brexit.

“We already have 450 lichens on Colonsay, around a quarter of all lichens in Britain, for instance, and 36 different types of fern.

“I think that as things move forward and concerns about the environment grow the islands will have enormous importance.

“I see rewilding becoming a national government decision, where islanders are encouraged to rewild the land.”

It’s a glimmer of hope in a depressing 24-hour news cycle predicting all-out climate catastrophe.

And while the longevity of Scotland’s remote islands is certainly not guaranteed, Byrne believes the younger generation can step up to the plate.

“In very recent years there’s been a definite sign of not just young people coming to Colonsay but young people with something to offer.

“The main way old people like me notice is that young people are now coming forward and running things like the hotel or village hall. For many many years, we ran stuff but now the young people are taking over.”

Read more on Scotland's islands:

On this day 1930: The evacuation of St Kilda

12 paradise islands in Scotland you must visit

.jpg)