On November 11, 1919, at 11am, Britain observed its first ever two-minute silence to honour those who had lost their lives in World War One; a tradition that still stands over 100 years later.

At the time, the Manchester Guardian reported the “hush” that fell over the city when the silence was observed:

“The hush deepened. It had spread over the whole city and become so pronounced as to impress one with a sense of audibility. It was a silence which was almost pain ... And the spirit of memory brooded over it all”.

In 1919, the physical and mental wounds of the war were still fresh. But the memory of the Great War lives on today, with Remembrance Day still marked on November 11, (Armistice Day) and poppies - a common sight for soldiers on the Western Front - still the symbol of remembrance.

Around Remembrance Day, it’s often, naturally, the two devastating World Wars - which saw tens of millions lose their lives - that come into focus as we reflect on the sacrifices made by those who served on land, sea and air.

Yet Remembrance Day is a memorial day not just for the soldiers who fell in the World Wars, but for all members of the armed forces who have died in the line of duty.

Since the end of WWII in 1945, there have been a number of conflicts and overseas interventions involving British forces, and sadly, British casualties.

These conflicts are often forgotten about by the wider public, but those who served in them don’t have the same luxury.

Many service people still live with the scars - physical and mental - of more recent wars, from the loss of fellow soldiers to PTSD and life-long injuries. For them, November 11 isn’t only about remembering the soldiers of wars long gone by, but of troops more recently fallen too.

'We'd been sent into an empty shell'

Often nicknamed “The Forgotten War”, the Korean War broke out in 1950, and saw almost 100,000 British soldiers deployed over three years of bloody conflict.

At the close of the Second World War, Korea was split into the communist Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) and the American-backed Republic of Korea (South Korea).

Though both Russia and America withdrew their forces from 1949, tensions between the north and south of Korea continued to deepen.

On June 25, 1950, the North Korean Army launched an offensive against the south, leading the UN Security Council to call on its members for help.

A number of troops were quickly sent over to defend the Republic of Korea, but northern progress was fast - with soldiers quickly taking the South Korean capital, Seoul, and driving South Korean and American troops to Busan in the south.

By October 1950, however, UN forces had pushed back, capturing the North Korean capital of Pyongyang by October 19. By late November, they came within 40 miles of the Chinese border.

The advance led to the Chinese People’s Liberation Army intervening, pushing troops south once again and claiming Seoul. Eventually, UN forces and South Korean forces recaptured Seoul in March 1951

After the bloody battle of The Battle of the Imjin River in April 1951, the mobile phase of the war was ended. By June, the Soviets indicated they were willing to begin peace talks.

Agreements could not be reached, and two years of static fighting followed. Eventually, an Armistice was signed on July 27, 1953, but the conflict technically never ended: a border still exists between North and South Korea today, with tensions still extremely high.

Ronnie Wilson, from Leith, Edinburgh, was just 20 when he was deployed to Korea to conduct border patrols along what is today referred to as the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).

Though his regiment knew they were going abroad, their destination wasn’t revealed until around a fortnight before deployment. The name “Korea” hardly shed light either - given Ronnie “didn’t have a clue where Korea was” at the time.

In spite of the devastating, bloody years of war that had just passed in the country, little was known about the war in Britain, with Ronnie admitting that he and his fellow servicemen “had no idea what we were going into”.

Ronnie considers himself “very lucky” to have been deployed in 1955, after the war’s end, with his active service involving mainly border patrols - with little conflict.

Yet on arrival in Seoul, South Korea’s capital city, what he saw shocked him nonetheless:

“The place was completely desolate...in Seoul, I don’t think we saw a single building that was standing...we’d been sent into an empty shell”.

In the absence of fighting, it was the temperatures that caused Ronnie the most suffering in Korea, with standard-issue uniforms failing to protect troops from the icy conditions:

“The worst thing was the cold, when we were there it went down to minus 25 [degrees celsius]...we slept in old nissan huts - at night we used to fill a basin of water indoors...by the morning it was frozen solid”.

Though Ronnie eventually returned to civilian life, he wasn’t one of those who forgot about the Korean War and the lives it claimed.

As part of the now-defunct Korean War Veterans Association, he helped erect the UK’s only memorial which lists all the names of the 1,114 British men who died in the Korean War.

Thanks to its historical position immediately after the Second World War and preceding more globally recognisable Cold War conflicts, the Korean War is often eclipsed in public memory.

This is in spite of around five million deaths in the conflict - over half of which were civilians, making the Korean War’s civilian death rate higher than that of World War Two or Vietnam.

'We just didn’t stop...we were constantly moving'

The Gulf War, fought from 1990-91, saw the second largest single deployment of British troops since the Second World War, with around 35,000 British servicemen and women serving in the campaign.

The conflict arose after the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq in 1990, following collapsed talks over oil production and debt repayment.

Iraq did not recognise Kuwait’s independence and annexed it, with Iraqi president Saddam Hussein declaring Kuwait the 19th province of the nation.

Western powers were afraid that Iraq may invade Saudi Arabia next, taking control of the region’s oil supply.

Then-US President George Bush called for the creation of a multinational force to deal with Saddam Hussein.

To prepare for defensive action, Bush ordered a total of 430,000 US troops and 53,457 British troops be deployed to protect Saudi Arabia.

Economic sanctions were imposed against Iraq by the UN, with an order for Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait. The deadline of January 15 1991 for withdrawal was ignored by Iraqi forces, however.

The next day saw a devastating air assault launched against military, economic and communication targets in Iraq and Kuwait.

A ground offensive began on February 24 1991, with Kuwait City recaptured on February 26.

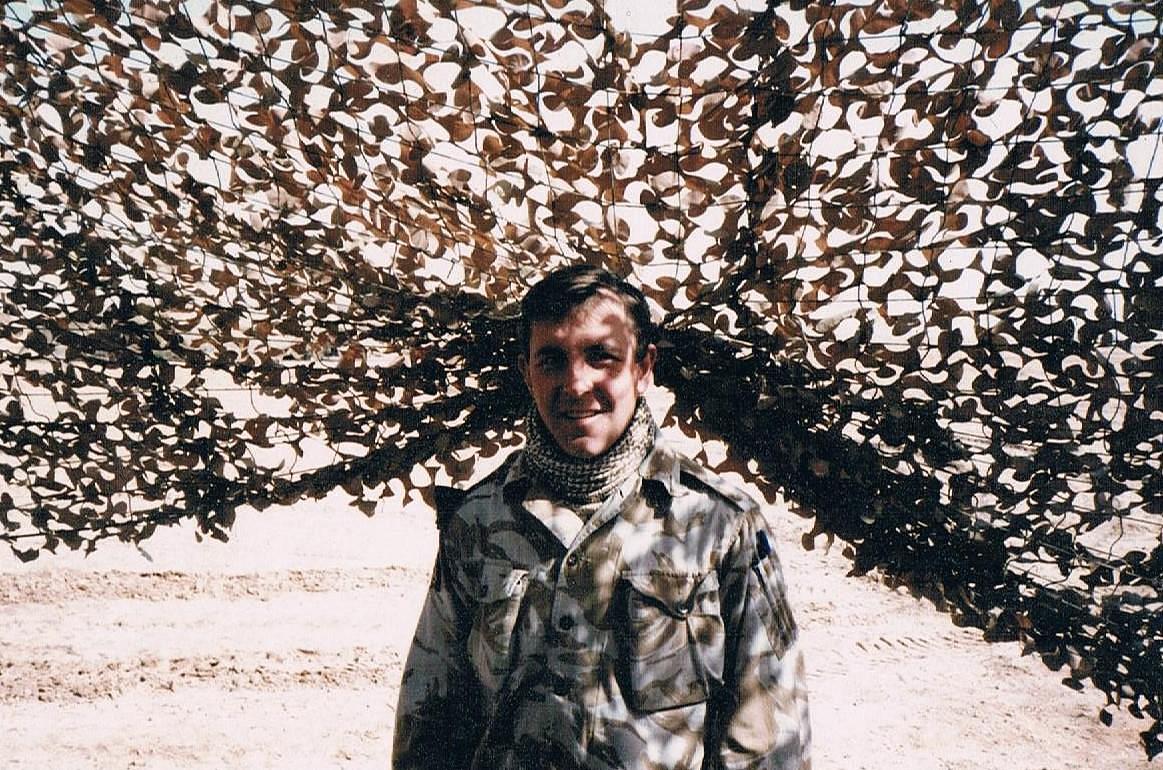

Iain Boyle, from Hastings, East Sussex, was one of those who experienced that ground offensive first-hand.

Attached to the Regimental Aid Post, Iain’s job on the battlefield was to support and act as a defence to the medics, who worked from a military ambulance. He remembers the days of the ground offensive as “a complete blur”:

“We just didn’t stop...we were constantly moving...I would open the doors of the ambulance to absolute chaos, blood everywhere”.

He recalls that, as a member of the ambulance crew in an ill-armoured vehicle, he had an average life expectancy of just four hours while in the midst of fighting - a fact he and his fellow troops faced up to with “dark humour”:

“I remember setting a timer for four hours, then when it went off and we were all still alive, we cheered”.

The troops made it to Kuwait, but, as a final act of destruction, the Iraqi Army set fire to over 500 oil wells, causing lasting environmental damage and huge plumes of smoke.

“The sky went black”, recalls Iain, who remembers the smoke rendering him “unable to see my way to the van...it was like we’d been covered in coal”.

Though Iain was not wounded physically in the conflict, he saw things during his time in the gulf that he’s carried with him years afterwards, receiving counselling for PTSD in more recent years:

“It’s when you see civilians who have been killed...that comes back to get you”.

A ceasefire in the war was called by President Bush on February 27, with Iraq agreeing to abide by UN resolutions a few days later.

The agreement included requirements for Iraq to end its programmes for weapons of mass destruction, return all Kuwaiti property and recognise Kuwait as an independent nation.

In spite of this, Hussein continued defying UN arms inspections and resolutions over the next ten years, partially motivating the invasion of Iraq by British and American forces in 2003.

Gulf War illness

Not long after the conflict had ended, soldiers who had served in the Gulf War began reporting unusual illnesses.

Previously fit and healthy soldiers from around the world reported suffering from a range of chronic symptoms like muscle pain, chronic fatigue, reduced coordination, muscle pain, rashes, diarrhoea and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Though some of these symptoms are common in all veterans, a 2009 study discovered that veterans of the Gulf War were two to three times more likely to report symptoms compared to other veterans.

In addition, they were twice as likely to report a poorer quality of life and PTSD.

The exact causes of Gulf War illness are unknown, but it has been suggested that a range of exposures to biological, radiological and chemical hazards - along with medical countermeasures intended to protect service people - may have caused the symptoms.

Iain is one of those who believes he and his family have been affected by Gulf War syndrome, with his daughter suffering from ongoing bowel problems, while his wife contracted cancer on his return from the war.

Some of his friends from the conflict have also suffered with what they believe are Gulf War-related ailments, such as epilepsy and malformations in not just themselves, but their children too.

Unlike veterans in some other countries, no compensation has ever been made available to Gulf War veterans in the UK, with a 2005 tribunal concluding that, while “Gulf War Syndrome” may be a usefully umbrella term for conditions associated with the conflict, it cannot “be characterised as a syndrome in medical terms”.

It’s a fact Iain feels somewhat resentful about today, saying that while he signed up “happy to give my life for my country”, he didn’t expect to be made “a guinea pig”.

He believes that coming into contact with depleted uranium on the battlefield may have been responsible for his later ailments; a risk which he feels he and his fellow service members were not well-informed about.

Coming from a family of military service people - including a great uncle who served in Korea - Iain believes that it’s “important to remember these other conflicts [outside of the world wars] on Remembrance Day”, with the knock-on effects still being felt by many in the UK today.

'I’d come back from Bosnia a completely different person'

After the break-up of former Yugoslavia in 1991, a civil war erupted in the new Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina, with armed conflicts beginning in 1992. It was an ethnically-rooted conflict which was characterised by genocide and bitter fighting.

On February 29, 1992, the multi-ethnic Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina passed an independence referendum - but political representatives of the Bosnian Serbs boycotted the referendum and did not accept its legitimacy.

Shortly afterwards the Bosnian Serbs, supported by the Serbian government, mobilised forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina to try and secure ethnic Serb territory.

War and vicious fighting spread across the country and ethnic cleansing took place. An estimated two million people were displaced as a result.

In 1992, the UN deployed a “protection force” in Bosnia, UNPROFOR. The protection force was asked to protect aid convoys running in the Bosnia region by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR).

British presence in Bosnia was later reinforced, with the British contingent’s area of responsibility in Muslim-Croat territory in central Bosnia.

They found themselves in the middle of vicious fighting within months as Muslims and Croats turned on each other while also fighting the Serbs.

An end to this conflict was brokered by the UN in February 1994. However, hostilities continued and in 1995, the Bosnian Serbs attempted to deter air attacks by taking 350 UN troops hostage

In July and August of 1995, the Bosnian Serbs recaptured “safe areas” and murdered thousands of muslims, as well as launching a mortar attack on a crowded marketplace in Sarajevo.

In response, the UN gave the green light for the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) to strike back, with air attacks on the Bosnian Serbs launched soon after.

The bombing, alongside an offensive by the Croatian Army, led the Bosnian Serbs to the negotiating table, with a ceasefire agreed on October 5 1995, and a peace pact signed on November 21.

A peacekeeping presence continued in the region however, and the horrors of the conflict were far from ancient history in 1996 when Tim Brown, of Hambleton in Yorkshire, arrived in the region as part of the Adjutant General's Corps.

He describes his role there as “basically just a presence, a protective force”, but adds that it was “seeing things during my time there” that triggered severe PTSD later in his life:

“I went to a village at one time, where there was a blown up bridge with people below digging...I didn’t know what they were doing at first until I walked up and realised it was a mass grave, with women and children buried there...the people digging them up were trying to give them a proper burial”.

At the time, says Tim, there was an “unwritten rule” in the forces which dictated that you shouldn’t tell your friends and family about what you’d witnessed while serving, but it didn’t stop his loved ones from noticing the psychological damage he’d suffered:

“My ex-wife said I’d come back from Bosnia a completely different person”.

It would take decades until the extent of this damage would become apparent, with Tim’s PTSD triggered by the death of his mother in 2016:

“For a while I couldn’t even say the word ‘Bosnia’ without breaking down...I got help through Combat Stress who helped take some of the guilt away that I’d been feeling...they made me realise that my presence [in Bosnia] helped those people get a proper, dignified burial”.

After leaving the services, Tim became a lorry driver, before realising that “sitting in a truck with my thoughts all day wasn’t the best thing”. Somebody recommended he hand in a CV to the Royal British Legion Industries and he quickly landed a job as Fulfilment Team Leader at social enterprise Britain's Bravest Manufacturing Company.

This year, he and his team are marking Remembrance Day by producing “unknown Tommy” silhouette statues of varying sizes which any member of the public can purchase and display to commemorate the fallen.

All proceeds from the project will be funneled back into the charity, which helps servicepeople, people with disabilities and unemployed people to find work and lead independent lives.

Tim is also involved in promoting the “Tommy Club”, a membership club designed to support veterans of recent conflicts and ensure they receive the best care possible post-conflict.