Insight: Me and John McAfee - the extraordinary story of the Scots writer in search of the truth

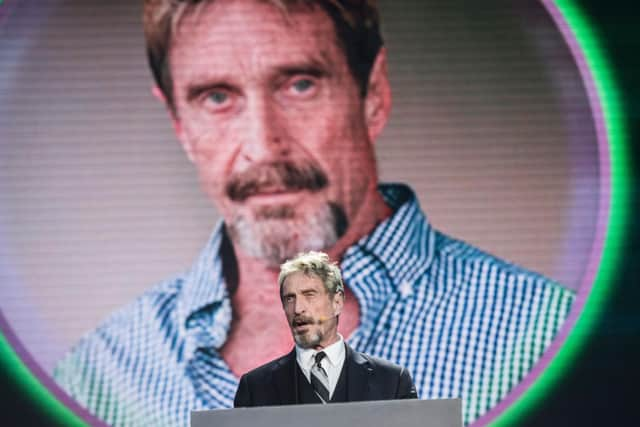

The mercurial programmer who amassed a fortune during the personal computing boom? The dotcom era proto-playboy who built a yoga retreat before chasing the thrill of flying open cockpit aircraft over the New Mexico desert? The hedonist who retreated to a Caribbean enclave, surrounding himself with pump action shotguns, bodyguards, and a harem of young women? The two-time US presidential candidate turned fugitive who went on the run after the murder of his neighbour?

Biographies, Mark Twain once observed, are but the clothes and buttons of a man. In McAfee’s case, can you realistically hope for more than lint and loose threads? His is a life of multiple acts, each as rich in drama and intrigue as the next. But they are buttressed by smoke and mirrors - the constructs of its complex and volatile protagonist, a man who amplified his mythology and misdirected those who came looking for the definitive narrative. When you tell the story of a master manipulator, can you ever hope to find the truth?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I’d like to think so, I have thought about it,” says writer Mark Eglinton, allowing himself a laugh. “I’ve thought, ‘Could he have sold me a dummy on a number of things?’ I don’t think so. Everyone who’s worked with John McAfee likes to think they’re the one that’s going to get the truth. It’ll never be the entire truth. But given the circumstances, the point he was at in his life, and the relationship we had, I do think I probably got closer than anyone else had.”

I am speaking to Eglinton exactly a fortnight after McAfee was found dead in Brians 2 prison in Sant Esteve Sesrovires, near Barcelona. Hours previously, Spain’s highest court, the Audencia Nacional, had approved the 75-year-old’s extradition to the United States, where he was facing multiple charges of tax evasion, fraud, and money laundering.

When the news broke, Eglinton went upstairs to his office in his home near St Andrews, sat at his desk, and cried. It was here that the best-selling author and ghostwriter had forged an intimate relationship with McAfee, talking over Skype nearly every day for six months to try and unpick a man with the brightest of minds and the darkest of appetites. Together, they retraced the topography of McAfee’s extraordinary journey, from its dizzying peaks in Silicon Valley to its deepest troughs in the Belizean jungle.

The resultant book, ‘No Domain: The John McAfee Tapes’, had already been completed by the time of McAfee’s death, the fruit of their near daily conversations between the autumn 2019 through to last summer, when McAfee was in hiding in a semi-abandoned hotel in the Catalonian coastal town of Cambrils.

Eglinton hopes it will be the definitive account of his life, from start to end, and he is currently writing an epilogue to take stock of the recent tragic events. The book, he says, will feature “explosive” material. The question is, can it provide the answers people want to hear?

For a story which flits breathlessly from one sun-kissed locale to the next, the unlikely relationship between McAfee and Eglinton began in altogether less salubrious surroundings. One drookit Tuesday afternoon in September 2019, the writer was driving with his wife from Edinburgh to Fife when his mobile phone lit up. McAfee’s Skype ID was on the screen. Eglinton and his wife looked at one another. “You’ve got to answer it,” she told him. “He might never call again.”

The communication was premature, if not unexpected. Eglinton had earlier sent McAfee a few messages on Twitter, enquiring if he’d ever thought about writing a book. The initial replies were “bizarre,” to the point that the Scot wondered if there was any point in continuing. The call changed everything. “I pulled over at a petrol station in Kinross in the pissing rain and answered,” Eglinton recalls. “There was McAfee on the other end, wearing dark sunglasses, looking crazy. From there it started.”

‘He was always drawn to the underbelly. His world was the gutter’

It is a familiar image, one which came to define the twilight of McAfee’s life - that of a charismatic and destructive genius motivated almost entirely by instinct, bare chested, tattooed, and sun ravaged, battling enemies both real and imagined. “The media has portrayed me as paranoid,” he once said. “I am a poor judge, since if I am paranoid, it is a paranoid mind judging itself.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne of the foundational ironies of McAfee’s life is that his ubiquity and fortune were the products of a distinctly utilitarian innovation. In 1986, he was working as a contract programmer for the defence contractor, Lockheed, when two brothers from Lahore, Amjad Farooq Alvi and Basit Farooq Alvi, devised the first known computer virus, capable of infecting the boot sector of PCs.

The siblings did so not out of malice, but curiosity, and their creation piqued McAfee’s interest. He designed one of the first ever antivirus programs and set up his eponymous firm to distribute it for free on bulletin boards, a precursor to the worldwide web. Within the space of three years, around half of America’s Fortune 100 companies had installed it on their networks, paying McAfee handsome licensing fees for the privilege. To this day, McAfee’s suite of products can be found across more than half a billion devices the world over.

But their progenitor pursued a different path. Long before the firm was bought out by Intel for £5.5 billion, McAfee - a dual British-US national who was born in Gloucestershire and raised in Virginia - had resigned and sold his stock for around £60 million, maintaining only sporadic contact with a few technicians and programmers. With that, one of the earliest tech trailblazers left the corporate world behind.

“John wasn’t interested in that,” Eglinton reasons. “He’d rather talk to guys on the street, vagrants and drug dealers. He was always drawn to the underbelly of society. His world was the gutter. That might sound disparaging, but it’s not. It gives you an understanding of the man he was.”

The subsequent chapters of McAfee’s life are so wildly disparate as to defy summary, with the only common thread a desire to indulge his every impulse. “I asked him about his ambitions,” Eglinton remembers. “He told me he never had any. I think he was just blown by the wind.”

A peripatetic existence took him first to Colorado, where he purchased a sprawling estate and set up his own yoga retreat, employing pagans to beat drums, and penning a series of books of spirituality which he would later caustically disown. While on a flight to Nepal, McAfee read a magazine article about light sport aircraft, and he soon swapped transcendental meditation for visceral thrill-seeking. He squandered millions of dollars in New Mexico and Arizona trying to popularise aerotrekking, which involves skimming open cockpit aircraft across the desert floor. It was a minority pursuit, and a high-risk one. McAfee’s 22-year-old nephew, Joel Bitow, was killed in a crash.

Come the financial crisis of 2008, his lavish, and often reckless, investment decisions came to inhibit his choices. He sold off his private airport, and a slew of mansions - several of which he had not even stepped foot in - and decamped to Belize. He was not yet 63, but his retreat to the margins marked the beginning of the end.

At first, McAfee jumped headfirst into a hedonistic lifestyle at his newly-purchased villa on the island of Ambergris Caye. A sign on its gate read: ‘Never mind the dog: beware the owner’. But retirement did not suit him. Before long, he bought two-and-half acres of jungle land, built a compound and then a laboratory, where he planned to synthesise antibiotics from rare flora native to the banks of the Río Nuevo.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMcAfee was compelled to venture deeper, amassing a network of armed security guards, and buying stun guns, handcuffs, and batons for the local police force. The idea, or forlorn hope, was to clean up Carmelita, an impoverished community plagued by drug-related violent crime.

The Belizean authorities, however, suspected McAfee’s biotech plans were a front for narco-trafficking, and raided his home. He told Eglinton that senior figures in the Belize government were corrupt, and wanted rid of him. The writer believes McAfee had good reason to fear for his life, but characterises him as the architect of his own downfall.

“Here was this gringo wandering into the local village, turning up at the bar full of dangers and the local town’s criminal element,” he says. “He may have seemed like this innocent guy at the beginning, and he was probably seen as a novelty. It changed as soon as he started meddling. I don’t think he went there looking for chaos. Chaos found him by virtue of the fact he tried to fix things, and you can’t.”

Eglinton believes the root of McAfee’s restlessness - or recklessness - was the suicide of his abusive, alcoholic father when he was just 15. “It had a very profound effect on him, and not necessarily in the way you would think,” he suggests. “He wasn’t upset about it at the time, he was relieved. It signalled the moment at which his need to respond to any form of authority ended.”

In the heart of darkness

Worse would follow. Much worse. In November 2012, a 52-year-old US national by the name of Gregory Faull was found dead at his beachfront home in Ambergris Caye, with a single gunshot wound to his head. He was McAfee’s neighbour.

The previous month, Faull had formally complained to Belizean authorities about McAfee, singling out his “dangerous” security contingent, and the “vicious” pack of dogs he kept at his property. The day before Faull was killed, four of McAfee’s dogs had been poisoned.

McAfee was named as a “person of interest” in the subsequent investigation, and although a Florida court would later order him to pay £18m to Faull’s estate in a wrongful death claim, he was never charged with any crime in connection with his death. In truth, he did not wait to find out. He went on the run from Belize, repeatedly insisting that Faull’s murder was a failed hit on him. McAfee was an unorthodox fugitive, employing fake dreadlocks, a multicoloured beanie hat, and a tampon among his props to feign disguise, and enlisting the media’s help to tell his side of the story.

A documentary crew from Vice Magazine even joined him as he made his way to Guatemala. But when one of the journalists uploaded a photograph revealing their location via the image’s metadata, McAfee was arrested for entering the country illegally. Only by faking a heart attack did he prevent being sent back to Belize. Instead, he was deported to the US.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEglinton said he pushed McAfee over Faull during their interviews, and that he dismissed the allegations in their entirety. “I made a promise to myself that if I got the strong sense that John McAfee had killed a man in Belize, I would have walked away from the project,” he says.

“By the time we discussed it, I had a good sense of when he was telling the truth, and when he was being a little bit evasive. When we talked about Gregory Faull, I had no doubt in my mind that this was something he did not do.

“In isolation, people will look at it and think it’s pretty clear, but there’s a lot of context surrounding what happened in Belize. He made the decision to move from the beach to the jungle.

“I said to him, ‘This is just ‘Heart of Darkness’ you’re living, what were you thinking?’ He said, ‘That’s preposterous, what are you talking about? ‘Heart of Darkness’ was a story of psychosis’. And I said, ‘Yeah? Is that not where you ended up?’ He replied, ‘Yeah, I suppose. That’s what happened’.”

Other damning allegations later emerged about McAfee’s erratic spell in Belize, ranging from sexual assault to his numerous teenage girlfriends, including former sex workers. Eglinton said he did not approve of McAfee’s behaviour, or in particular, his relationships with young women. Asked how the world will remember him, his reply is immediate.

“Probably not how he wanted,” he says. “I think 50 per cent of people hold him up as a hero, particularly in the hacking community, and 50 per cent of people think he’s a nut.”

‘I didn’t get emotionally involved’

But wait a minute. Let’s just take a breather. Belize? Murder? Drug dealers? Jungle laboratories? Let’s rewind to the familiar terra firma of the petrol station in Kinross. How, I ask Eglinton, did he end up chronicling this frantic ride, without having signed any collaboration deal or non-disclosure agreement?

The 51-year-old has carved out a successful career writing acclaimed books across the fields of sport and music, including the autobiographies of Michael Owen, the former Liverpool and England footballer, and Michael Lynagh, the former captain of the Australian rugby team. John McAfee, I suggest, is something of a departure.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEglinton laughs. “It came about as a result of my desire to understand people who’ve lived interesting lives,” he explains. “With McAfee, I got the impression he’d tried a couple of times to work with people, but he told me most of them were naive, or couldn’t comprehend the kind of life he’d lived. Very quickly we got into an understanding where he knew I was probably the right person to do this.”

The interviews, Eglinton says, were invariably eventful. McAfee often looked like he had just got out of bed. One time, the Scot watched on the screen as McAfee’s wife, Janice, brought him a coffee, only for him to demand that she take a drink of it first. “I remember asking John when it was that he began to fully trust her. He told me, ‘I don’t think I can’.”

The plan, at first, was for Eglinton to ghost McAfee, telling his story in his own voice. But when interested publishers asked for McAfee’s address and he, in turn, insisted that he would only be paid via cryptocurrency, things became “complicated.” The compromise is a biography, still told in McAfee’s own distinctive southern baritone. “It’s a conversation between us, and it’s still his voice, it’s still his autobiography,” Eglinton explains. “It’s just presented slightly differently.”

Even so, I am intrigued by the issue of authorship, which seems as relevant to Eglinton’s book as it was to McAfee’s life. He was, by his own admission, a “master of disinformation and obfuscation,” curating his own persona, and cultivating relationships with a handful of journalists to spin a Pirandello-style web.

One, Jon Swartz, a senior reporter at MarketWatch, a US financial news site, interviewed McAfee several times. After his death, he wrote a piece recalling one of their early exchanges. “‘The thing is’, John told me, trying to suppress a grin, ‘is only I know what is the truth. Your job is to figure out what that is’.”

Another reporter, Joshua Davis, wrote a lengthy profile of McAfee for Wired, only for McAfee to later brand him naive, insisting that he had had “great fun at his expense.” Did Eglinton ever get the sense that McAfee was playing him?

“Not at all,” he responds. “John did test people, and he tested me at the beginning. I think that Skype call at Kinross was part of it. He’d messaged saying he’d call in a couple of days, but ended up calling 15 minutes later.

“In some of the early talks, he ramped up the drama. I think he wanted to see what my reaction was - would I retire from it, or be impressed by it? I never really gave him any of that. I didn’t get emotionally involved, and I think he saw me as someone who wasn’t a pushover.”

‘People jump to wrong conclusions’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEglinton is a personable, articulate, and thoughtful interviewee, and the fact that his previous books have been shortlisted for prestigious literary awards is testament to both his skill as a writer, and his judgement of character. Even so, I can’t help but wonder whether the shock - and loss - he has experienced over the past fortnight might have obscured his view of potential pitfalls ahead.

In spite, or perhaps because of McAfee’s death, his extraordinary story continues to play out at a dizzying pace. His widow has cast doubt over his suicide, posting on social media that she does not accept the narrative that has “been spread by the malignant cancer that is the MSM [mainstream media]” and its “unnamed sources.”

For his part, Eglinton says he was, and remains, “very surprised” by events, describing McAfee as someone who, even in his final years, “did everything he could to stay alive.”

He is frustrated by the lack of information coming out of Spain, but is prepared to accept an uncomfortable truth. “The facts of the the matter might be that John committed suicide,” he tells me. “If that’s the case, it’s very sad, it’s most unexpected, and it doesn’t tie in with the narrative, but if that’s what happened, that’s what happened.”

Others, however, are unlikely to be satisfied. Over the past two weeks, a slew of conspiracy theories have surfaced from the depths of the internet, linking McAfee to the partial collapse of an apartment block in Florida, with fabricated tweets attempting to suggest he had files proving government corruption stored in the building. QAnon influencers have also questioned the circumstances of McAfee’s death, with the tasteless hashtag #McAfeeDidntUninstallHimself trending on Twitter.

Egilnton finds himself embarking on promotional activity amidst this toxic mix of grief, anger, resentment, and deceit, and is realistic enough to expect friction. His aim is to cut through the myths to show that McAfee was a man before he became a meme. There is, he says, “uncomfortable” speculation that his taped conversations with McAfee constitute a so-called dead man’s switch, and while he is keeping the book’s revelations under wraps for now, he is not invested in any conspiratorial mindsets.

“People jump to wrong conclusions,” he insists. “They have made an assumption that these tapes are material John was going to release to the world. The reality is they are tapes of our interviews. The book was already in production, so there’s a confluence of two things.”

Yet the reality of the situation Eglinton finds himself in is nuanced and convoluted, with multiple parties seeking to impose their own narratives with which to frame McAfee’s death. His libertarian streak, evangelism for cryptocurrency, and playful political dalliances - he ran for the White House in 2016 and 2020 - won him a cult following on the fringes of the internet, while his social media rants against government control, the taxation system, and latterly, Covid-19 vaccines, saw him garner more than one million followers on Twitter.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe rise of McAfee’s reinvented outlaw persona - a cross between Bill Gates, Tony Stark, and Hunter S. Thompson - in tandem with the proliferation of far-right media outlets sparked by Donald Trump’s presidency has created a captive audience. Eglinton is pragmatic enough to understand and accept that. Post Hill Press, the independent US publisher which is releasing his book, has previously released titles by the far-right conspiracy theorist, Laura Loomer, and the embattled Republican congressman, Matt Gaetz.

The book is also being promoted by right-wing activists such as Jack Posobiec, the former One America News Network presenter, and Eglinton himself has appeared on ‘War Room: Pandemic’, the widely banned podcast run by Steve Bannon, the firebrand former chief strategist in the Trump White House.

“I knew you were going to get me on this,” Eglinton says when I mention Bannon’s name. Does he think he has a responsibility over how he promotes the book?. “I’m torn at this point with the promotional activity, because on one hand, I’m still reeling from John’s death,” he replies. “I was close to him, I liked the man, and we worked on this project which he’ll never read. That makes me sad.

“At the same time, I know from Janice and her conversations with John that he wanted this story out there. He told me himself he was going to promote it. I want that story out there.

“Now, if someone’s going to turn up on my doorstep and ask me on their show to talk about it, selectively I will. Cynically, I’m looking at this point for the maximum audience who might be interested in a title like this.”

Time will tell how the world greets Eglinton’s book, and the extent to which he can control it. It represents his best possible version of the truth about a man he believes was locked in a perpetual search for affirmation. “John always felt he was misunderstood,” he says. “He spent his life trying to address that, but I don’t think he ever had the context or space to do that.”

But concepts such as truth are relative in John McAfee’s story, which has always been more thriller than gospel. Even in death, one suspects, its final chapter has yet to be written.