Opium and entrepreneurs - the Scots who built Singapore

Chasing the Dragon, the second volume of the Singapore Saga (Monsoon Books, 2019), continues to document the major role that Scots played in the early development of Singapore, if not always in the best light.

One might wonder what accounted for the early commercial success of Singapore’s traders. One answer was Indian opium, which represented about 40 per cent of the export trade in the early decades of the settlement. China had long prohibited the use, cultivation and import of opium, but the trade was continued illegally though bribes to customs officials in Canton.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEnter William Jardine (1784-1843) and James Matheson (1796-1878), two Scottish traders who founded Jardine, Matheson and Co in 1832, which quickly came to dominate the trade in China tea and Indian opium. Jardine became the acknowledged leader of the business community in Canton, known locally as the Tai-pan, or ‘great manager,’ and also as the ‘Iron Headed Old Rat,’ after he bested a Portuguese captain who struck him over the head with a cudgel.

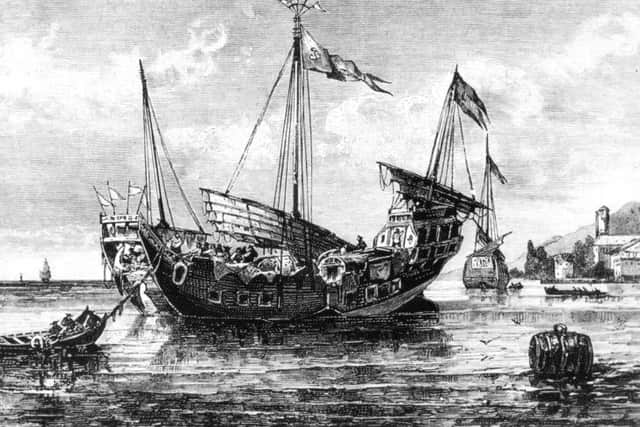

They made huge profits from their opium trade, as their fast clippers and small craft – known as ‘sandhoppers’ and ‘crawling dragons’ – spirited opium up and down the Chinese coast and inland on the minor rivers, carrying Christian missionaries to serve as interpreters in exchange for the opportunity to make converts. Yet this was not enough for Jardine and Matheson or the merchants back home in Britain, who wanted more Chinese ports opened to trade, by force if necessary. What they needed was an incident, and then they needed a war.

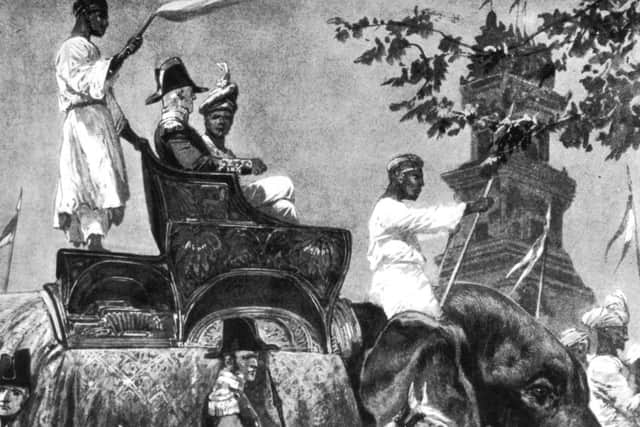

They did not have to wait long. In March 1839 Commissioner Lin Tse-hsü arrived in Canton and confiscated all the opium in the merchant houses and ships in the harbour, which he then flushed out to sea. Jardine was in Genoa on holiday on his way home to retirement in Scotland when he heard the news. He immediately cancelled and travelled to London, where he met with Lord Palmerston, the new foreign secretary. Jardine persuaded Palmerston to go to war with China, to punish them for their outrage and to advance British interests in the region. He advised Palmerston on how to prosecute the war, how many vessels and soldiers would be needed, and the terms of the treaty once the war had been won: compensation for the opium lost, the reopening for Canton and additional ports – such as Fuzhou, Ningpo and Shanghai – for trade, an indemnity for the cost of the war, and the ceding to Britain of Hong Kong, with its sheltered deep-water harbour. Britain consequently launched and won what became known as the First Opium War (1839-1842), which concluded with the Treaty of Nanking, in which the Chinese agreed to virtually all the terms that Jardine had originally pressed for.

Jardine did not live long enough to enjoy his victory and retirement. After a long struggle with stomach cancer, he died in 1843, aged 59. The fates were kinder to Matheson, who retired to Scotland in 1842, where he bought the island of Lewis for two hundred pounds sterling. He died peacefully in Menton, France in 1878, at the age of 82. The company was carried on by their nephews, and evolved into the Jardine Matheson conglomerate, headquartered in Hong Kong but now incorporated in Bermuda. Somewhat ironically, Singapore’s own share of the opium market began to decline from the 1840s onward, although the local opium concession contributed nearly half of the government revenues for most of the 19th century.

There were other Scots of course, whose achievements in Singapore were more benign, such as Dr Robert Little (1819-1888), an Edinburgh surgeon, who warned about the dangers of opium addiction and condemned the opium trade; his two younger brothers John Martin and Matthew Little, who founded the department store John Little and Co in 1853 in Commercial Square (present-day Raffles Place), which became the premier department store in Singapore until it was taken over by Robinson and Co in 1955; and Charles Andrew Dyce (1806-1864), the Aberdonian merchant, architect and artist, whose delicate sepia and watercolour paintings of early Singapore are now housed in the National University of Singapore Museum.

One of these deserves special mention, since his work produced a major benefit for his countrymen back home. Dr William Montgomerie (1797-1856), another Aberdonian, came to Singapore with Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819, the year the settlement was founded. In addition to serving as senior Surgeon until 1844, he started a plantation at Bukit Selegie. None of his crops flourished, but one day he made an interesting discovery. Walking along the edge of his plantation on a very hot day, he noticed a woodcutter paring a log with his parang. Although the man was sweating profusely, he never lost his grip on the handle of his blade. When he questioned the man, the woodcutter told him the handle was made from the sap of the gutta-percha tree, which he identified for him in the jungle. He told Montgomerie that when the sap was collected, it hardened, but would grow soft again when placed in hot water. There it could be formed into any shape, and would set firm into that shape when it was removed from the water.

Montgomerie thought that the sap would be very useful in making handles for surgical instruments. He wrote an article on its properties and sent some samples to the Medical Board in Calcutta, and, through his brother-in-law, to the London Society of Arts in London. Early attempts to use gutta-percha for surgical instruments were not successful, but it was soon after used in the insulation of telegraph and submarine cables. Then in 1845 the Reverend Robert Adams Patterson (1829-1904) created the first ‘gutta’ golf ball in Carnoustie, by hand rolling balls from lumps of gutta-percha that had been softened in boiling water. These cheaper balls quickly came to replace the much more expensive leather balls stuffed with chicken and goose feathers, which Patterson had not been able to afford as a poor student at St Andrews. They revolutionised the sport by making the game accessible to the common man, for which generations of Scots are surely grateful. Gutta-percha became an important Singapore export, and made personal fortunes for Diang Ibrahim (1810-1862), the Malay Temenggong of Singapore and Johor, and his Scottish business partner, William Wemyss Ker.

A final coincidence. The author recently came upon an obituary in The Scotsman, which reported that Charles ‘Harry’ Wilken passed away prematurely in January 2010, aged 61. He had joined Jardine Matheson in 1972 and risen through the ranks to become president of Jardine Matheson International Services in Bermuda, the local ‘Tai-pan.’ (www.scotsman.com/news/obituaries/charles-harry-wilken-president-of-jardine-matheson-international-1-788031)

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHarry Wilken and the author both came from Elgin, and Wilken was his patrol leader in their local scout troop.

Singapore Saga 2: Chasing the Dragon by John D Greenwood is published by Monsoon Books at £8.99. Out now.