Mystery of 'illegal distillery' found deep in Scottish woodland

Now archaeologists believe the ruined buildings in Loch Ard forest, that stretches between Aberfoyle and the foothills of Loch Lomond, may have been the headquarters of an illegal whisky making operation that ran on an industrial scale.

The remains of the Wee Bruach Caoruinn and the Big Bruach Caoruinn – including their large corn drying kilns – have now been documented by Forestry and Land Scotland, which owns the woodland..

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFLS Archaeologist, Matt Ritchie, who was responsible for investigating and recording the sites, said:

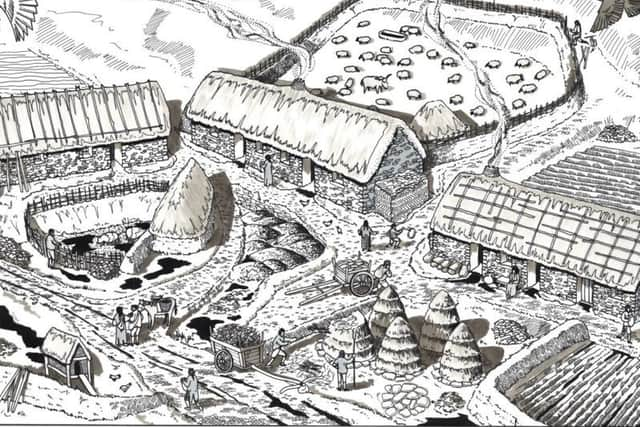

“The farmsteads of Bruach Caoruinn were flagged up by the local history society as being of interest – the surviving narrow buildings are unusually long, and are associated with two large corn drying kilns.

“Set in a relatively inaccessible area yet close to Glasgow, in close proximity to water and with strong associations with a number of the important families in the district, it is possible that the site was a hidden distillery, producing illicit whisky in the early 19th century.”

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, illicit distilling was rife in the Highlands of Scotland.

The government had wanted to extend its control over whisky production and the Excise Act of 1788 banned the use of small stills that made less than 100 gallons (450 litres) at a time.

Commercial legal whisky was of poor quality due to the high rate of tax imposed on the malted grain used to make whisky.

To cut costs, the large lowland distilleries began to use unmalted raw grain. This produced an inferior drink called corn spirits.

The illicit stills paid no tax and continued to use good malted grain, and so, once it had been smuggled to lowland markets, it fetched a higher price than the whisky made by the licensed whisky distilleries. Customers for the illicit whisky were not just farmers and workers but the rich, even the judges and lawyers whose job it was to stop the trade.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMr Ritchie added: “You can malt grain in a corn-drying kiln, and the long narrow buildings would have been perfect for fermenting and distilling whisky.

"I wonder if there had been illicit whisky being made at Bruach Caoruinn on an almost industrial scale. There is no surviving evidence, bar historical whispers. But is this really surprising?"

Known as far back as 1540 , the land is thought to have had an association with hunting, with iron-making, and with livestock husbandry – goats, horses, cattle and, in the late 18th century, sheep.

The farms were abandoned in the 1840s and, by the 1860s, had fallen into ruin. However, the narrow roofless buildings have survived surprisingly well, having been afforded some protection by the forest that used to surround them.

Investigation of the structures, including the archaeological measured survey and historical archival research, was carried out with the assistance of the Scottish Vernacular Buildings Working Group, AOC Archaeology, Alan Braby and Mairi Stewart.