Victorian trolling: ‘Would you like some vinegar with your Valentine?’

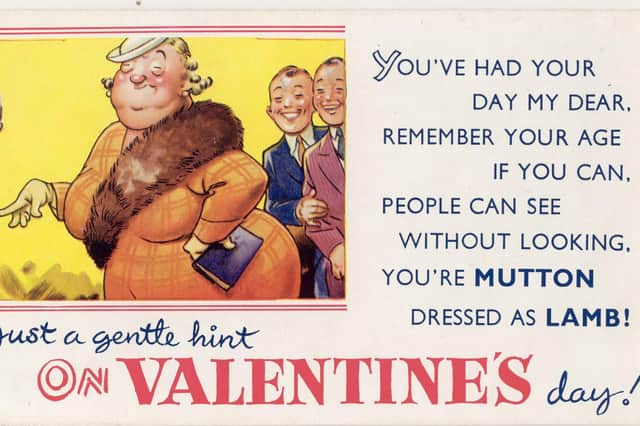

We seem to be warned daily that society is turning into a crueller place to be. These days, especially, we’re told that there is a new form of blood sport available to anyone with a mobile phone and an internet connection: anonymous online ‘trolling’.Rewind 150 years - surely our genteel great-great-great-great ancestors would never had stood for that - would they? And would they actually have had the technology to do it anyway?If you take a trip back to 1840s Scotland, then you have your answer: “The Vinegar Valentine”.Of course, it has always been the case that written abuse could be delivered by post anonymously. In fact, before 1840 and its introduction of universal postage, the victim had to pay for the letter or card received, only to find that they had actually paid for the privilege of being abused.The first half of the nineteenth century saw literacy rates increase dramatically. You need only to look at the success of Charles Dickens’ serialised “Pickwick Papers” (1836) to see how demand for reading materials at all levels of British society could lead to fame and fortune through writing. Increased literacy meant more readers, more writers and more letter senders. And now that you had learning enough to write a letter, then why not write a card too?The emerging, improved printing technology met popular demand, and thus printed items became cheaper both to produce and to buy. Letter writing and card sending in the UK grew exponentially as cheap penny postal systems expanded from the 1840s onwards. Printers in the UK cashed in on rising demand for these picture postcards and for greeting cards celebrating all types of occasion.Valentine’s day cards in particular became annual money-spinners with their floral designs, their elaborate rhymes and colourful images declaring love and affection.However - to invert the common saying - where there was ‘brass’, there was also ‘muck’. Commercial operators saw a way to cater to those customers who preferred something with a more acid streak. From the 1840s to the 1940s, firms such as Raphael Tuck, Edward Stern and the Illustrated Postcard S Novelty Company made substantial profits, not just selling the sugar-sweet Valentine models, but also from the more abusive form of card: the “Vinegar Valentine”.Vinegar Valentines were cheap printed cards with crude caricatures and often crueller verses mocking their recipients. By the mid-1850s, Vinegar Valentines were said to account for about half of all valentine sales in the United States. And the UK was not immune to their dubious charms. It has been estimated that by the 1870s, the Vinegar Valentines being sent in the UK each year totalled some three quarters of a million.No one was safe from this Victorian version of trolling. Class, gender, age and profession provided no protection against these often grotesque, spiteful but comic cards, sold for a penny and posted anonymously.The images and words they offered were meant to highlight the shortcomings of their recipients, and were often written as though the comments on the card expressed common opinions about their victim. Politicians were particular targets: “You’ve no more sense of honour, than has a rotten egg,/A scurvy politician, you, you’ll come at last to beg;/You’ll loaf around the corners, as you’ve often done before,/Until you’re but a common tramp, who begs from door to door.”Sometimes the verse was a direct attack upon its victim’s looks: “In prison you ought to be doing some time/For to wear such a face must be surely a crime...”Famously, Flora Thompson, in the thinly-disguised account of her life as a postmistress in a small English village, “Lark Rise to Candleford”, recalled receiving such a card in the 1890s, with a crudely-drawn caricature of her occupation and acid verses mocking her plain looks. She recounted that she was so disgusted, she threw it into the fire.Best-selling as they were, not everyone approved of these comic, but hurtful communications. As The Newcastle Weekly Courant commented in 1857, “The stationers’ shop windows are full, not of pretty love-tokens, but of vile, ugly, misshapen caricatures of men and women...”

Such merciless mockery continued for around a hundred years, but by the early twentieth century, tastes gradually changed. By the 1930s, the Vinegar Valentines were becoming increasingly unpopular, replaced by the cheeky, double-entendre seaside caricatures and the sunny holiday postcards of a later century.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite the cheapness of their paper and their ephemeral quality, a number of the 1800s Vinegar Valentine cards still survive, and these are now preserved in museums and archive collections. They serve to remind us that even on Valentine’s day, trolling was not a habit confined to the twenty-first century, and, as with many things that we deem our modern inventions, our gentle ancestors got there first:“I’m not attracted by your glitter/For well I know how very bitter/My life would be, if I should take/You for my spouse - you rattlesnake...”Starting on Monday: They’re back exclusively in The Scotsman - Edward Kane and Mr Horse, the most enjoyable duo since Holmes and Watson! “Edward Kane and the Vinegar Valentine” by Ross Macfarlane QC appears every day next week in The Scotsman and concludes in a two-part episode on Valentine’s Day in Scotland on Sunday