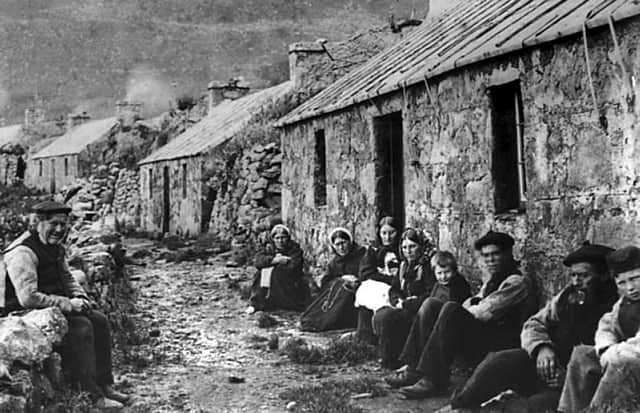

St Kilda and an island of vanishing people

Hunger and cold pervaded the 11 St Kildan men stuck in a nightmarish bid to live after the boat due to collect them from their goose hunting trip never showed.

What they did not know, while clinging on to the bare face of Stac an Armin in the St Kilda archipelago where they had gone to hunt geese, were the horrors unfolding at home on

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHirta where small pox had killed up to 90 per cent of the population.

When the men finally got off the rock and returned, houses were empty and silent with whole families never seen again. The island was now home to 26 orphans.

The outbreak of 1727 is considered a key turning point in the story of the vanishing population of St Kilda, which was evacuated of its last permanent resident 90 years ago this weekend after a plea was made to the government for help to leave given the deepening struggle to forge a life there.

After the outbreak, a bid to repopulate St Kilda contributed to the demise of its sustainable culture, according to author Mark Bridgeman, who has been researching the history of St Kilda in a collaboration with West Highland Museum in Fort William.

Mr Bridgeman, of Perthshire, said: “The outbreak was a turning point with St Kilda then losing its individual identity and its ability to be self sufficient.

“The landlords, the MacLeods of Harris and Dunvegan on Skye had to repopulate the island, and people were sent from the other Hebridean Islands to increase the number and rebuild a viable community. This might sound altruistic, but was more likely to be an economic necessity, since the islanders paid a rent in woollen tweeds, seabird oil and feathers.

“St Kilda became less self-sufficient with the arrival of new islanders, partly because the new population coincided with the increase in visits from steamships. Their own farming

and food gathering systems began to fade as they began to rely more on outside influences. At the same time, many young men started to leave as news of opportunities

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Adelsewhere were passed on to St Kilda by these new visitors.”

READ MORE: Meet the St Kildans – from shoes made from goose heads to eating puffin porridge

Over the decades that followed the outbreak, St Kilda became a source of fascination for the new breed of Victorian traveller with new income generated by selling and bartering of goods.

A mass migration of St Kildans to Australia brought further fundamental change with 36 out of 110 residents setting sail for Port Philip, Melbourne, from Liverpool in 1852.

Funded by the Highlands and Islands Emigration Society, which was supported by landowners and other elite, including Queen Victoria, the passage came at a high human cost.

St Kildans making up 12 per cent of the passenger list, but 45 per cent of deaths of those on board.

Accounts from Australia speak of “another shipload of Gaelic-speaking Highlanders and Islanders, some of them penniless and sick”.

The late Eric Richards, emeritus Professor of History at Flinders University, Australia wrote that St Kildans “had been desperately unlucky” given they were “biologically,

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Adlinguistically and culturally unsuited and unprepared for their migration”.

The experience may have steadied the flow of people from St Kilda for a time.

Mr Bridgeman said: “News of the emigrants’ ill-fated venture eventually made its way home and may have contributed to the little movement out of the island until the First World

War.”By the 1930 evacuation, the 36 remaining islanders were wearied by a series of medical emergencies and appalling winters. For all of them, saying goodbye was the only option they had left.