Scotland entered the 1970s facing a shrinking economy, soaring unemployment and rising inflation.

Communities north of the border were among the hardest hit by the ongoing collapse of Britain’s heavy industries, and the immediate future looked bleak.

The situation was not helped by the Conservative government led by Ted Heath, which decided it would no longer pursue a policy of intervention in stemming the industrial decline.

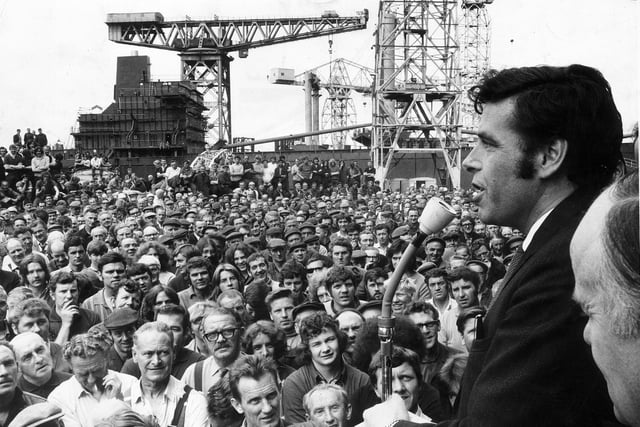

One memorable episode arrived in the summer of 1971, when the UK government announced it would not intervene in preventing the liquidation of one of Scotland's largest shipyards, the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders (UCS).

On July 30, with thousands of men at the loss-making yard set to join the dole queue, shop stewards Jimmy Reid, Jimmy Airlie, and others, made headlines far and wide when they announced they would stage a “work-in”, avoiding strike action and completing the yard’s remaining orders to prove to the government that the UCS was worth keeping open.

Delivering his iconic speech to the assembled masses at the yard, Jimmy Reid declared there would be “no hooliganism, no vandalism”, and most of all: “no bevvying”.

The campaign worked a treat, with the Tories agreeing to restructure the yards around two new companies the following year.

But while the result provided the former UCS workers with cause for celebration, there were darker times ahead for the nation as a whole.

At the end of 1973, the Conservatives introduced the Three-Day-Week measure in a bid to conserve electricity, the generation of which was in short supply due to the oil crisis affecting much of the Western World.

The dire situation was exacerbated further by a series of miners’ strikes, with the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) campaigning tirelessly for wage increases.

Amid all the gloom, however, there was a gleam of light on the horizon.

The discovery of oil in the North Sea off the coast of Aberdeenshire was a turning point in the fortunes of Scotland and the UK at large – and the Scottish National Party, for so long a fringe political power in Scotland, was keen to capitalise. The party launched their infamous “It’s Scotland’s Oil” campaign to strengthen their support – and, to some degree, it worked.

At the October 1974 General Election, the SNP, which had previously won just a single seat, secured 11 MPs, taking mostly Tory seats, and very narrowly helping Labour into No.10.

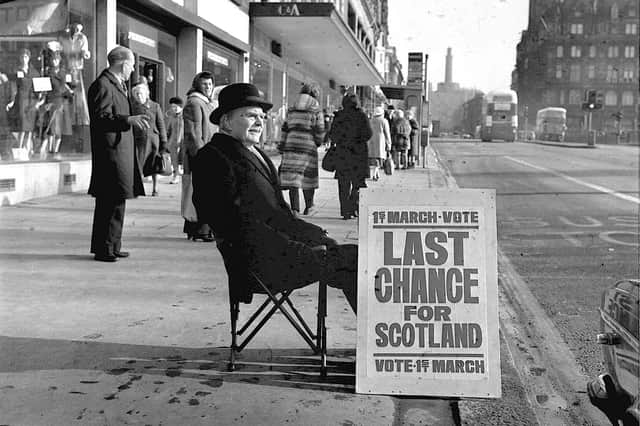

Calls for Home Rule grew louder than ever before and the Labour party duly relented, offering Scotland the opportunity to hold a referendum on the matter in March 1979.

However, while Scots voted 51.6 per cent in favour of devolution, it was not enough to meet the demands of a late amendment to the Scotland Act, which stipulated that a Yes victory would require the participation of at least 40 per cent of the electorate.

Within a matter of weeks, devolution defeat turned into utter despair for the SNP when the party lost nine of its seats at the 1979 General Election.

The nation was about to enter the Thatcher era and the notion of Home Rule was put to bed for a generation.

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions.

1. Discovery of oil

Workers add another section of pipe to the drill at BP's Forties Field oil platform in October 1975. Photo: Ian Brand

2. NUM picket

The NUM official picket outside lady Victoria colliery in Midlothian during the miners' strike of February 1974. Photo: Jack Crombie

3. 'No bevvying!'

Jimmy Reid the convenor of the shop stewards during the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders dispute in 1971 Photo: Allan Milligan

4. Every vote counts...

The counting hall at Meadowbank stadium in Edinburgh as the Scottish devolution referendum votes come in, March 1979. Photo: Albert Jordan