The lost merry customs of a traditional Scottish Hogmanay

Known as Nollaig in the Highlands and Western Isles, no work was done during the period but men gave themselves up “to friendly festivities and expressions of goodwill,” with special licence given for enjoyment and merriment.

A common saying of the festive period was often shared: “The man whom Christmas does not make cheerful/Easter will leave sad and tearful.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHogmanay was referred to as either ‘Night of the Candle’ or ‘Night of Blows’ given one ritual which involved a man having a dry cow hide placed over his head before being beaten like a drum as he and his friends moved around their village.

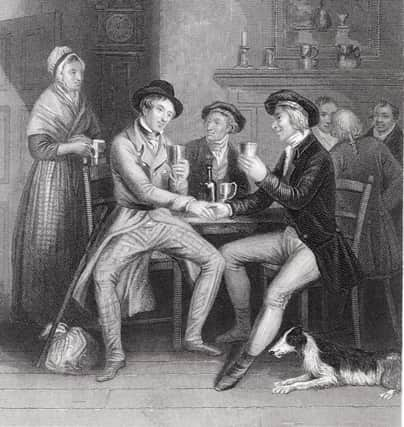

Usually led by a bagpiper, the group would move around each house, turning anti-clockwise, striking the walls and reciting rhymes to raise the householders. As doors opened, the group would pile into each home to receive refreshments such as oatmeal bread, cheese, flesh and a dram of whisky, according to John Gregorson Campbell in his encyclopedia of customs The Gaelic Otherworld.

The idea was to “drow the animosities of the past year in hilarity and merriment,” Campbell wrote.

Holly also played a role in the party. It was hung in the belief it would keep the fairies away but boys were also whipped with a branch of the greenery.

Every drop of blood spilled counted the years the boy would live and although it sounds fairly grim, it was reportedly a ritual practised in good jest among friends.

Meanwhile, a slice of cheese given at the gathering was considered to have a “special virtue” if the piece contained a hole.

Hogmanay night was sometimes referred to as New Year’s Night with the fire in the home playing a central part in the superstitions during the countdown to midnight,

It was feared that letting the fire go out would invite bad luck into the home with only householders - or a friend - allowed to tend it. Candles were usually lit as back up to ensure a flame remained in the house on December 31, lending to the name Night of the Candle as a result.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNew Year’s Day, like the first of every quarter of the year, was a great ‘saining’ day across the Highlands and Islands when rituals were at their most intense to protect cattle and houses from evil.

Juniper was burnt in the byre, animals were marked with tar, the houses were decked with mountain ash and the door-posts and walls and even the cattle were sprinkled with wine.

The morning of January 1 started with a dram poured by the head of the household with a spoon of half-boiled sowens, or oatmeal husks, considered the poorest of all the foods, given for luck.

It was unlucky for a woman to enter the house, or anyone to come in empty handed. A young man entering with an armful of corn was considered a joyful omen but a “decrepit old woman asking for kindling of her fire was a most deplorable omen,” Campbell wrote.

First footing might be thin on the ground in 2020 but there is no doubt this has long been a special time of year – and will long continue to be so.