Glasgow fights same battles decades after Edinburgh’s HIV epidemic

Gilbertson was one of thousands of young people who became hooked as the city flooded with heroin in the late 70s and early 80s. She is telling her story on award-winning director Stephen Bennett’s Choose Life: Edinburgh’s Battle Against Aids. The new documentary is about the HIV epidemic which began to take hold of the capital 40 years ago, and went on to kill Gilbertson’s partner and many others.

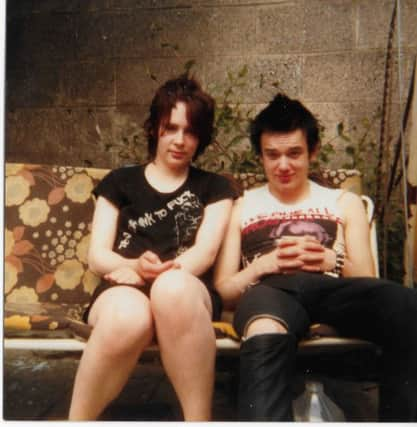

Gilbertson can remember the exact moment she fell in love with Raymond: “a sweet, flamboyant boy” 18 months her junior. “We were outside a pub and we had been dating for a wee while, and there was going to be a huge fight between the punks and the skinheads,” she says. “He grabbed me and we ran away from it and we were both giggling and he said ‘I’m a lover not a fighter,’”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy then most of the young people Gilbertson knew were using heroin. They shared needles stolen from the bins in the Edinburgh City Hospital. They didn’t know about Aids. Not yet.

Then Raymond found out he was HIV positive. He came home and told Gilbertson everyone he’d slept with or taken drugs with had to be tested. He became sick and was admitted to the City Hospital’s Aids ward. “What is an Aids death like? It’s terrifying; medieval,” Gilbertson says. “They wore those full suits like you see in films about Ebola. Raymond was very unwell. He got tumours in his brain, he went blind, he was convulsing.”

Gilbertson was also diagnosed with HIV, but – unlike Raymond – she was lucky. The virus did not progress to Aids. She came off heroin and now runs a charity called Recovering Justice which campaigns for the decriminalisation of drugs and the destigmatisation of users.

Her campaign work is driven by her memories of those dark days. As Raymond lay dying, she grew progressively angry, but Raymond was resigned. “He looked at me kind of confused and he said: ‘But we’re junkies. This is what we deserve,’” Gilbertson says. “So eventually, what society had been telling him, he believed.”

Today, Glasgow is in the grip of the biggest outbreak of HIV in Scotland for 30 years. A rise in the dual injecting of heroin and cocaine (speedballs) and in homelessness is thought to be behind a ten-fold increase, with 100 new cases between 2015 and 2017.

Though everyone now understands the virus is spread by dirty needles many addicts have gone back to sharing. It seems the lessons of the past are being ignored. It doesn’t help that drugs policy is reserved. The Misuse of Drugs Act, 1971, prevents Glasgow City Council from opening a safer consumption room where heroin could be taken under supervision.

The hostility towards a measure which has been proven to work elsewhere in Europe is all too familiar to those who lived through the Edinburgh Aids epidemic. On the documentary, there is footage of the minister responsible for health in Scotland, John MacKay, arguing that the distribution of clean needles would just encourage more young people to consume. By the time doctors persuaded the government to change its approach, hundreds had been infected and dozens had died.

“Edinburgh was the Aids capital of Europe. Scotland is now the drugs death capital of the world,” Gilbertson says. “There’s a lot of fantastic organisations doing a lot of great work. But if we have an outbreak in Glasgow amongst our most vulnerable population then we have forgotten our history; we have forgotten how to look after people; we have forgotten to take community responses; we have forgotten evidence-based policy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“That this outbreak could happen, and that it could take so long for anyone to respond… what does it say about the way we regard those who have nowhere to live? If it had been with any other community, action would have been taken much more quickly.”

Perhaps – like Raymond – those injecting have also internalised the message that they are not worthy of support or attention. “When your culture and your community treat you in a certain way for long enough, you begin to believe it,” Gilbertson says.

The sudden influx of heroin to Scotland in 1979 had its roots in international turmoil. The overthrow of the Shah in Iran – and the prohibition of opium growing by the Ayatollah – saw opium production switching to the Afghanistan/Pakistan border where resistance leaders fighting Soviet occupation used it to fund their operations.

Choose Life captures the sheer speed with which estates such as Muirhouse and Pilton found themselves at the epicentre of the drugs and HIV crises, and the fear that spread once the general public began to understand that contracting the virus was effectively a death sentence.

Roy Robertson, a GP in Muirhouse for 30 years, recalls that in the mid-1970s there were between 50 and 100 drug users in Edinburgh. By 1980-81 that had risen to more than 5,000.

With the rise in drug use came a rise in crime as addicts struggled to fund their habits. “House-breaking went off the scale,” says Tom Wood, former deputy chief constable of Lothian and Borders Police. “And it wasn’t subtle. People were just kicking down doors and picking up whatever they could.”

Ill-equipped to deal with the number of offenders, the force treated it as a war. Gilbertson remembers being shouted at and intimidated. “I saw policemen hit women in front of their children. That was really shocking to me because I thought: ‘Who do you turn to when the bad people are wearing uniforms?’”

But it was difficult for the police too, especially once the HIV virus began to spread. Les Taylor, a constable in Leith, remembers being spat at as he went to make an arrest. The man told him he had Aids, laughed and said now he would have it too. Taylor didn’t know what he was talking about.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne of the first medical experts to understand the threat to drug users in Edinburgh was Dr Ray Brettle.

A senior registrar at City Hospital’s regional infectious diseases unit, Brettle had encountered some of the world’s first Aids patients during a fellowship in North Carolina. But – unlike many in the UK – he had also worked with long-term drug users, so he was quick to spot the potential for the HIV virus to spread among injecters as it had in the gay community.

On his return to the city in 1983, he tried to warn health officials and politicians, but his concerns were ignored. “Amongst the rest of the medical staff there was either ambivalence or they weren’t interested at all,” he says. “People didn’t think this was going to be a big issue. For two years most people thought I was being a bit over the top.”

By 1985, however, an HIV test had been developed. Brettle wanted to set up a testing and counselling clinic in the hospital. But even though the threat was now clear, he had to fight to persuade not only the Scottish Office, but his own colleagues that drug users who were unlikely to live more than five years should be a priority.

“Winning over the health boards wasn’t too difficult, but any money you won meant taking resources from other people, so you also had to explain to your colleagues why they had to wait in line,” he says.

“The heart and chest doctors wanted to know why all this money was being spent and the subtext was: ‘These people are going to die anyway and they are pretty much the bottom of the pile, so why are you bothering?’”

After much campaigning, Brettle was allowed to set up his clinic. Within the first six months, 200 users had been tested. Two thirds of them turned out to be HIV positive.

“The only reason the money was spent in the end is that drug users were the bridge into the heterosexual community,” he says. “You had to persuade people that the virus wasn’t confined to those widely perceived as ‘undesirables’, but would be transmitted to a lot of other people as well.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

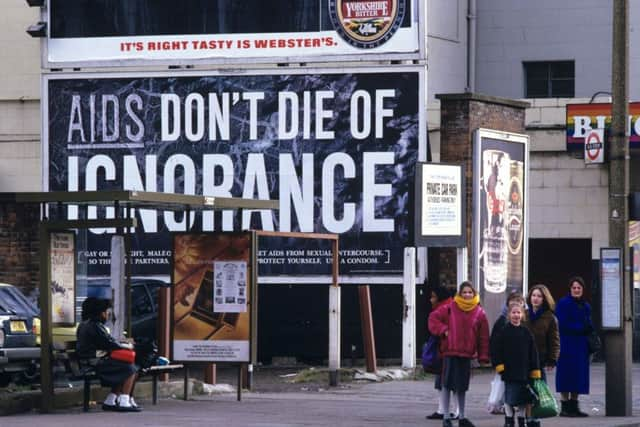

Hide AdAs the documentary shows, those were febrile years. In the general public, there was a sense of panic. By 1987, the government had launched its terrifying “Don’t Die of Ignorance” public information films, the two most chilling of which featured a tombstone and an iceberg.

In the iceberg video, directed by Nicolas Roeg, the viewer was warned that there was now a deadly virus, that anyone could catch it from sex with an infected person (it didn’t even say ‘unprotected’) and unless we acted now (ie stopped having sex) it was going to get much, much worse.

As the fear grew, so did the stigmatisation. There was a great deal of scaremongering. Many people believed you could catch the virus from a toilet seat or a teacup. Some medical experts forecast compulsory testing followed by isolation for those infected.

Fear made affected drug users volatile too. In the early years, when he was known as Dr Death, Brettle was threatened so often he went ex-directory.

Because his was the only clinic of its kind in Edinburgh, it brought together rival factions, who fought even as they were being treated, as well as those angry with Brettle for trying to stop them injecting.

“My patients would say: ‘You are manipulating me like you say I am manipulating other people.’ I would answer: ‘You are right, but I am doing it to try to look after you,’” Brettle says.

“We had various rules or guidelines. I would say: ‘I will do lots of things for you, but I will not lie for you. If you commit a crime here then we have to phone the police.’”

Brettle’s tactic was to try to get users off heroin and on to methadone, but – apart from Roy Robertson – he was the only doctor prescribing it. Gradually the demand increased so much, he was told he could only dispense to those who had the virus; so tensions rose again.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was a time of sorrowful reckoning too. “At that point HIV equalled Aids equalled a death sentence,” Brettle says. “But strangely it was only when people stopped injecting that they started to look at their lives and then what it meant to have HIV would hit them and they would ask: ‘I am not going to get to 30, am I?’ It was difficult to answer: ‘I don’t think so.’”

Then: a miracle. Scientists began developing antiretroviral drugs. ATZ – around from 1989 – was not hugely effective, but triple therapy launched in 1996 effectively granted those with the virus a reprieve.

“I had told one patient: ‘You need to get your son over because I don’t think I can keep you well for much longer,’” Brettle says. “But triple therapy became available in the next six months and, although his eyesight was badly damaged, he survived.

“So there was this turning point which takes us beyond the end of the documentary when things suddenly changed. Within my professional lifetime, we went from HIV being a death sentence to a chronic disease; we went from ‘I can treat the problems you are going to develop, but I can’t treat the underlying cause’ to ‘if you take these pills every day, you’ll be fine’.”

Director Stephen Bennett, whose documentary Dunblane: Our Story won a Scottish Bafta, was just about to leave school when Aids began to hit the news. “It was a time of fear,” he says. “I remember people worrying about getting their ears pierced.

“The iceberg public information film was huge back then. Even now, when I watch it, I get goose bumps.”

Bennett wanted to tell the story of the Edinburgh epidemic with authenticity. He wanted to make people understand to what extent everyone was operating in the dark back then. But he was also conscious of the parallels with the current HIV outbreak in Glasgow and the way it is – or rather isn’t – being tackled.

“I think it’s an abomination that we have an epidemic again,” he says. “In Edinburgh, in the 80s, the problem was the removal of needles [by the police], the confiscation of drugs paraphernalia, which encouraged users to share.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“In Glasgow, the HIV epidemic is not happening because there are no clean needles – I think the police have learned that lesson. It’s happening because users are injecting heroin and cocaine and because so many people are homeless. And also because of a widespread sense of worthlessness.”

Brettle is similarly despondent. “I was watching a news story on safer drugs consumption rooms the other night and it struck me that nothing has changed,” he says. “The frustration of trying to persuade other people to do what you believe needs to be done is always there.”

Brettle says, after the Aids crisis subsided, methadone came to be regarded as dangerous and so there was a move away from substitution therapy. In any case, there is no sub therapy where cocaine is concerned.

Like Gilbertson, Brettle believes the safer drug consumption rooms are key. “We seem to have forgotten you cannot influence the behaviour of others without being regularly in touch with them,” he says. “Ideally, you would send out hundreds of staff because if you can afford one-to-one counselling it works very well.

“But that is not really feasible now and injecting rooms would be one way of ensuring regular contact with those individuals.”

Last week, Bennett had an experience which brought home to him how urgently we need action.

“I was at the King’s Theatre with my two boys and we came out at night and there was a man and woman openly injecting drugs outside. I was trying to take my boys away, but at the same time saying: ‘Did you see that?’ so they would realise what was going on.

“For me, as a Glasgow director, this documentary is a cri de coeur,” he says. “Not only is it a record of what happened in Edinburgh in the 80s, and an attempt to show the net effect of decisions made along the way, it is also a wake-up call for what’s happening to my city.”

Choose Life: Edinburgh’s Battle Against Aids is a Two Rivers Media production for the BBC. It will be shown on BBC1 at 9pm on Thursday