‘Brain in a bottle’ developed by Scots scientists

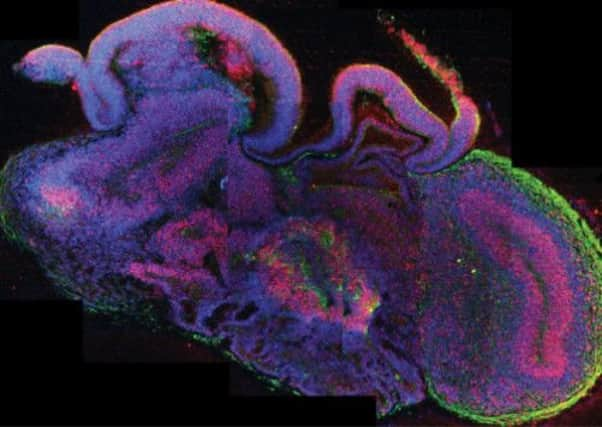

Grown in the lab using stem cells, the hollow “organoids”, measuring just three to four millimetres across, have a structure similar to that of an immature human brain.

The researchers, including a team in Edinburgh, wanted to produce a biological tool that could be used to investigate the workings of the brain, better understand brain diseases and test new drugs.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut they said they were still far from the science-fiction fantasy of building a working artificial brain – or even replacement parts for damaged brains.

Scientists have previously grown other laboratory models of human organs from stem cells – the building blocks of the body with the ability to turn into different types of tissue – including livers and intestines. But the human brain is a much more complex structure.

The scientists’ work, detailed in the journal Nature, included nourishing the immature cells in a gel-like “matrix” that let the complex structures develop.

These were then transferred to a spinning “bioreactor” which provided extra nutrients and oxygen, enabling them to grow much larger in size.

After two months, the “mini-brains” mimicked the layered structure of a human brain growing within a developing foetus.

Professor Juergen Knoblich, of the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology in Vienna, who led the Austrian and British team, said: “We’ve been able to model one disease, which is microcephaly. Ultimately we’d like to move to more common disorders like schizophrenia or autism. We are confident that we might be able to model some of these defects.”

He said the extreme complexity and inter-connectivity of the adult brain made him “pessimistic” about the possibility of replacing whole brain structures with laboratory-grown versions.

Prof Knoblich added: “Our system is not optimised for generating an entire brain and that is in no way our goal.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Andrew Jackson, of the Medical Research Council’s Human Genetics Unit at Edinburgh University, and his team provided microcephaly patient cells and expertise to the study.

The medical geneticist said: “The organoid cell culture system gives us an exciting new way of studying the early events of brain development in tissue culture, to learn more about neuro- developmental disorders such as microcephaly.”

Scientists commenting on the research spoke of its potential and implications, but also its limitations.

Neuroscientist Professor Paul Matthews, of Imperial College London, said: “Treatments are still a long way off, but this important study illuminates part of the pathway to them.”

Stem cell scientist Dr Zameel Cader, from Oxford University, described the research as “fascinating and exciting”.

He added: “The structure they have generated is a long way from a real brain and the challenges for creating even a primitive foetal brain remain daunting.

“Hopes to recreate a real brain therefore remain distant. The proper organisation and blood supply of the brain are not present in this model and are major limitations.

“However, their model is audacious and the similarities with some of the features of a human brain are really quite astounding.”