Scotland expects: Sacrifice on the Great War's home front

Private Mullholland had been a patient in a war hospital in Cornwall and was travelling back to Scotland for rest and recuperation in the family home when his train was derailed. The accident had tragic consequences. According to Private Mullholland, there were many severely wounded passengers, one of them a nurse who, despite sustaining a terrible leg wound, dragged herself around trying to bring succour to injured passengers. He said he could “hear the screams of women and children but never saw men work so heroically as those who assisted to release the poor people”.

He was deeply moved by the death of a woman and her young son, but she also had a baby daughter who survived. According to the private, the family had travelled from Scotland to see the baby’s father who was stationed in England. He was about to embark for France and the family wanted to be united before his departure. It was a traumatic, tragic end to a family reunion.

Advertisement

Hide AdTraumatic loss was not confined to the theatres of war. Home Front deaths and their tragic consequences were, for the most part, lost to the narrative of the global carnage that was taking place, particularly on the Western Front.

The conflict that started in Europe in August 1914 had, by 1918, produced millions of personal tragedies. Throughout the war, on a day-by-day basis, British and Irish newspapers published endless casualty lists under the headings, Killed in Action, Died of Wounds, Wounded, Wounded – Shell Shock, Missing, and Prisoner in Enemy Hands. The Times had the most comprehensive lists and on a daily basis, there could be as many as 5,000 names printed and the number seldom fell below 1,000. After the appalling losses in the 1917 campaigns the newspaper no longer published complete lists.

By 1918, overwhelming traumatic losses had brought with them a search for meaning. Lives were being lost and destroyed in a war which had become ethically and morally more questionable. Grieving parents were haunted by having to confront the death of a son, daughter, sometimes both. Furthermore, it was not uncommon to lose several sons. Two brothers from a mining village in West Lothian died on the same day. Both sons served in the Royal Garrison Artillery and they were both gassed on 14 September, 1918. One brother died in a Casualty Clearing Station, the other at a Base Hospital in France. Despite serving together, they were not united in their final hours.

Within the forces, the loss of life affected every social class. Herbert Asquith, married to Scots-born Margot Tennant, was prime minister until late 1916. The couple lost their son, Raymond, in September of that year at the notorious Quadrilateral on the Somme. Canadian-born son of a Scottish clergyman, Andrew Bonar Law, Scottish MP and wartime Chancellor of the Exchequer, lost two sons; Glasgow-born Arthur Henderson, leader of the Labour Party, lost his son; Sir Harry Lauder received a telegram from the Home Office on New Year’s Day informing him of the death of his only son.

From cities, towns, villages, glens and crofts, men, women and boys were lost to the dirty business of war. Death did not respect class or gender. Within the military nursing services and the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, over 500 women lost their lives as a direct consequence of their war service. There were also the deaths of women working in the war-related industries. Approximately, 700,000 women worked in the munitions factories and within that industry, 400 women died of exposure to Trinitrotoluene (TNT). There were also 250,000 women employed in agriculture and other labour intensive industries such as shipbuilding and furnace stoking, but there appear to be no official wartime statistics of women’s work related deaths.

However, military deaths and their consequences dominated the discourse on the futility of the war. Parents did not expect to outlive their children and it was often said that, “mothers died of a broken heart” and “fathers were broken” by the loss of their sons and daughters – unforeseen consequences of war.

Advertisement

Hide AdAs an outward demonstration of collective grief, street shrines became popular in cities, towns and villages. They were constructed by the local community, and varied in size, craftsmanship and content. Some were wooden boards, or thick wooden or metal plaques, which had the names of the war dead inscribed, painted or carved on to them. Many shrines were built into buildings with architectural recesses where wooden shelves or altars could be constructed. They were generally draped in flags and adorned with flowers. Some communities had religious emblems or statues as the focal point. They were erected as a labour of love and they were maintained by communal grief. In addition to these informal commemorations and dedications, there were regular “In Remembrance of the Dead” services, which were usually conducted “in praise of gallant and noble sacrifice”.

These were seen by some cynics as a means of controlling the outpouring of grief. However, it was not uncommon for mourning families to commission an “in memoriam” poem to be placed in a newspaper, usually written by the local clergy or a newspaper staff writer.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn their desperation to accept, or sometimes deny, their loved ones’ deaths, many distraught families, lovers and friends turned not to the established cultural and social expressions of mourning, but to the practice of spiritualism or a variety of beliefs and rituals. Alleged “psychic intervention” with dead soldiers, which began in earnest in 1915, was now a well-established, thriving business. In the absence of a body to grieve over, and denied the ritual of burial, thousands of bereaved families attempted to make contact with their dead loved ones.

There were, of course, any number of charlatans prepared to play on the raw emotions of the bereaved. The call on mediums and psychic healers had become so prevalent, according to one national newspaper, that in the West End of London alone, at least 300 “seers” had come to the attention of the authorities. Men and women were shamelessly making small fortunes out of the misfortunes of war. In response to these parasitic practices the Witchcraft Act (1732) and Vagrancy Act (1824) were used to bring about prosecutions.

However, spiritualism had its supporters and none more high profile than Sherlock Holmes’ creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who lost his son and brother in 1918. He became a devotee and in 1918 published The New Revelation, his study on psychic and spiritual phenomenon.

The widespread yearning for relief from the pain and anguish of war proved as fruitful for drug traffickers as fake spiritualists. On 4 February 1916, The Scotsman reported that in England two individuals were charged with giving cocaine to soldiers.

One week later newspapers reported that morphine and cocaine were being sold to troops, with one sensational headline reading, “Drugs for Soldiers”.

At Folkestone, a man and woman were sentenced to six months’ imprisonment with hard labour for selling cocaine on three different occasions to soldiers on home leave. Another report claimed there were “40 cases of the drug habit in one camp” – whose name was withheld. Under the Defence of the Realm (Consolidation) Regulation, NO40B (Cocaine and Opium), a committee was set up to examine permits to purchase cocaine or opium.

Advertisement

Hide AdDrug-taking was not a new phenomenon, but the war created a situation where, for some, it became the only means of dealing with a myriad of emotions, particularly fear, anger and loss.Loss is such a small word but with enormous meaning. Throughout the war, Scotland had more than its share, and it was not confined to the fighting fronts.

Throughout the war there were several military disasters on the Home Front. Two in particular are burned in the memory.

Advertisement

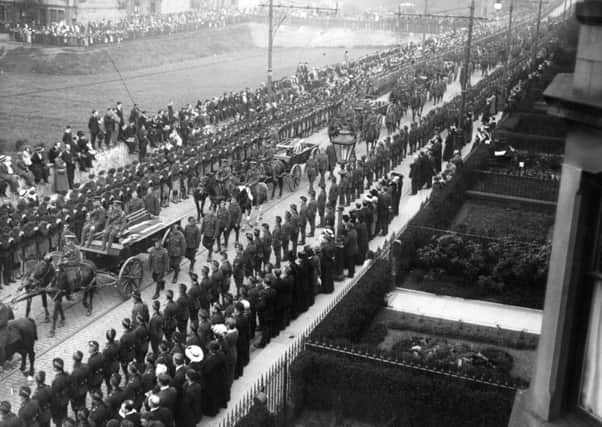

Hide AdOn May 1915, the Quintinshill rail disaster occurred near Gretna Green. The estimated death toll was 226, with 246 injured. The dead were primarily Territorial Army soldiers of the 7th (Leith) Battalion of the Royal Scots, who were on their way to Gallipoli.

And the final act of twisted fate began on New Year’s Eve 1918, when His Majesty’s Yacht Iolaire left the Kyle of Lochalsh for the Island of Lewis, carrying servicemen from Harris and Lewis who were returning home from the war. In the early hours of the morning, as it approached the port of Stornoway, the ship hit rocks and eventually sank. The final death toll was officially 205 of whom 181 were islanders.

Throughout the war years the Scots made a huge contribution and for the size of the nation, and their losses were substantial. It was estimated that the number of Scots serving in the Forces was 688,416. The numbers of returning sick, wounded, disfigured and psychologically traumatised have never been calculated. However, not factored into the wartime narrative of the Scots were the lives shattered due to the tragic, unforeseen consequences of the war.

Professor Yvonne McEwen, Professor of History, War and Conflict Studies, University of Wolverhampton, and Project Director of Scotland’s War (1914-1919) Visit www.scotlandswar.co.uk