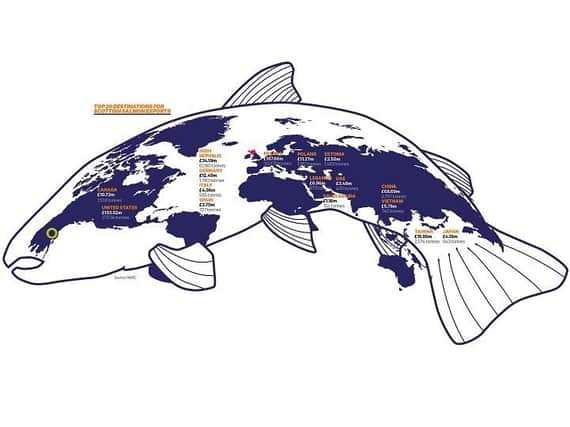

Scottish salmon proving export success around the world

From Japanese sashimi houses to the most upmarket Parisian eateries, from the cool of the fast-moving New York restaurant scene to the glamour of Middle East high-end hotels, Scottish salmon at the top of the seafood stakes.

It is seen as such a premium product that the markets where demand is growing indicate which countries’ fortunes are on the up, as sales reflect the rise of the middle classes with disposable income in emerging economies.

The farmed Atlantic salmon industry is comparatively new, created in the last 40 years, but it has huge potential.

The actual logistics of how salmon get from sea to plate is impressive, but along the way there are clues as to how the industry became one of Scotland’s success stories.

Salmon farms are dotted around the west coast and in Orkney and Shetland. They are major employers in the areas in which they operate, which is particularly important in these economically fragile communities.

Wester Ross Fisheries, which has three fish farms in Loch Broom, Little Loch Broom and Loch Kannaird, is a case in point.

Managing director Gilpin Bradley says: “We have been the largest private sector employer in Ullapool for the last 35 years. That is important because the Highlands have 58 per cent working for the public sector, so private sector jobs are scarce.”

The salmon, reared in freshwater for the first year of their lives and then in seawater for 18 months to two years, are first loaded live from the farms on to wellboats, containing large vats of water. You could say that, as a result, the salmon swim ashore.

Wellboats are equipped with cameras in tanks to monitor salmon behaviour and stress levels, and the water temperature is regulated to help keep the fish calm.

Each farm will have its own processing centre which again, because of the location, can be an important employer.

Wester Ross Fisheries’ salmon are processed at Dingwall, while Marine Harvest Scotland, which employs 1,000 people in Scotland, has a processing centre in Fort William.

Scottish Sea Farms, another major employer, sends salmon from its farms on the west coast to South Shian, near Oban, while its Orkney and Shetland-raised salmon goes to Scalloway on mainland Shetland.

At the processing sites, the fish are stunned and humanely killed, gutted and cleaned, packed in ice and loaded whole into polystyrene leak-proof containers, holding 22 to 25 kilograms.

They are labelled and will remain in this container for the whole journey, ensuring a traceable supply chain from the pen to plate, something terrestrial farming cannot guarantee.

Georgina Wright, head of sales at Marine Harvest Scotland, says that is not the only advantage the industry has over farming on land: “We are in charge of the whole value chain – farming, processing and selling to the end user – which means that we have the ultimate control on quality.”

The salmon is graded at this stage, as some will have been raised to even higher standards, to merit the Label Rouge accreditation, a sign of quality.

Celine Kimpflin, head of exports for Scottish Sea Farms, explains: “Label Rouge is a French denomination and Scotland was the first non-French country to achieve the label, which it received for its salmon.

“There are rules about density, feeding and welfare and only the very best fish get the label and a unique number for every single salmon.”

She says the market for these premium products is mainly across Europe – “in France, of course, but also Belgium, Germany, Luxembourg, Switzerland and Spain. It is a very small market, like organic, but it is high-quality and high-value.”

Any producer can work towards the label and most salmon producers in Scotland will have a share of the niche market.

The other salmon are graded in size, from two to more than nine kilos, as market demands differ around the world.

Larger salmon are sent to the sashimi chefs in Japan and China, while the European market prefers smaller fish with a uniformity of size to help portion control in restaurants.

As you would expect, the journey from here relies on speed to guarantee freshness. Wright says: “The fish go from farm to airport in 24 hours and can be on the table anywhere in the world within two to three days.”

The main distribution centre for the salmon industry is in Larkhall in Lanarkshire, and from here most of the containers are loaded on to lorries to head for Heathrow.

The industry would prefer to be able to operate more routes out of Scottish airports, but as yet the chilled facilities aren’t good enough to take the growth in exports.

Kimpflin says: “We are lobbying for better facilities at Scottish airports.

“As the Norwegians and Faroese go through Heathrow too, in times where there is high demand we are restricted.”

One route that has recently opened up out of Scotland is to Beijing, in China, and Wright says: “It opened in June this year and we are hoping long term it will make a big difference.

“China is a growing market. The first exports went there in 2011 and the market has grown year on year and potential is huge.”

It is this aspect of salmon exports that is perhaps the most fascinating – spotting potential in the market and pursuing it.

Marine Harvest Scotland exports to 11 destinations in China. Wright says: “Shanghai itself has a population of 25 million but it is also about per capita consumption too.

“The single largest buyers of salmon in the world are the US but in terms of their consumption of seafood it is low, so the long-term opportunity is high.

“France and Spain are the largest fish eaters in Europe but emerging markets like China, Asia and South Africa have growth potential.”

Around the globe, Scottish salmon has a reputation above that of Norway and Canada, but Scotland still has only 8 per cent of the market.

Kimpflin agrees that the growth markets are China, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan but says exporters need to be aware of politics. “Diplomatic issues between China and Norway, for example, gave Scotland an advantage for a while. Keeping an eye on the geopolitical situation and how that will affect trade routes – the relationship between Taiwan and China, for example – is one of the most interesting aspects of the job.”

Norway is the main rival of Scottish salmon and the country that dictates the market. It produces 1.2m tonnes of salmon compared with about 170,000 tonnes from Scotland. Competition also comes from the Faroes and Canada. The latter has cheap transport rates and so is targeting the Far East.

However, the advantage Scottish salmon has is its quality reputation, and growth is about building on the brand. Kimpflin says: “We do command a premium over Norwegian and it is usually a big gap, so it is worth protecting.”

Bradley says: “Scotland’s salmon farmers are ambitious and want to grow, and the frustration we all have is that we can’t meet the demand for the product, which outstrips supply.

“We understand the need for a regulatory framework but salmon farmers’ number one concern is looking after the environment in which they work. Their livelihood depends on it, and keeping the sea pristine will safeguard our future livelihood.

“More than half of the world’s seafood is farmed and the value of Scottish salmon is already worth more than the whole of the UK fishing industry.”

‘You can’t have great cuisine without great products’

French master chef Matthieu Garrel is a huge fan of Scottish salmon. He says: “You can’t have great cuisine without great products. This Label Rouge Scottish salmon reminds me of those we used to eat at home 15 or 20 years ago, when salmon was a rare treat, only served on special occasions.

“You can see and you can smell that it is a fish produced with care – its delicate colour, pleasant texture and subtle aroma of the sea are just like those of salmon in the good old days.

“It retains all its juices when cooked and that is a sign of top-quality fish.”

The Breton, pictured, who runs his own restaurant in Paris, has huge experience in the trade. After gaining qualifications in catering, Garrel left for England, working first in a three-star London restaurant and then in the first English Relais et Chateaux-approved establishment.

This early adventure, as well as improving his English language skills, taught him the importance of attention to detail, high standards and teamwork.

After his military service, Garrel returned to Brittany to work with Jean-Pierre Crouzil in Plancoet. In 1994 he moved to Paris to work with Gerard Besson, one of the “best artisan chefs in France”, then at Potel & Chabot and the Pays de l’Est restaurants, where he received training in management and cost control.

In 1996, Besson invited him back as chef de cuisine at Yachts de Paris. With this added experience, he felt ready to start up his own business.

He opened Le Bélisaire in the 15th arrondissement in 2001. His philosophy was to offer high-quality, bistro-style cuisine, based on technical precision, creativity and authentic products – all at the best possible price. It paid off.

Glowing reviews from customers and in good food guides bear testament to his talent, which was also acknowledged by his peers and culminated in him being elevated to Master Chef of France status in 2014.

For more information, visit http://scottishsalmon.co.ukThis article is taken from The Scotsman's Annual Food & Drink Supplement which can be read in full here.