Bill Jamieson examines the outlook for Scotland's exports

It certainly cannot be faulted, either for the comprehensive detail of its research – profiling 26 countries accounting for more than 80 per cent of current exports – or for its ambition. It also follows hard on its 2016 publication Global Scotland: trade and investment strategy 2016-2021 – which aimed to increase trade and investment in Scotland.

The new target, which foresees a near doubling of the value of exports, a £3.5 billion addition to GDP and the creation of 17,500 jobs, is a tall order at any time. It is especially so now given the highly uncertain circumstances we currently face, and the failure to meet previous targets set by the Holyrood administration – particularly disappointing given the 26 per cent fall in sterling against the dollar over the past five years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor the period 2010 to 2017 it had set itself a target of increasing exports by 50 per cent. But an analysis of the out-turn figures by the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) showed this target was not achieved: exports grew by 35 per cent over the period and, as a percentage of GDP, even fell back slightly. The rest of the UK remained the main destination for Scottish exports, though the share was reduced from 65 per cent to 60 per cent.

On a historical perspective, Scotland can claim a long and distinguished exporting history. From ocean-going ships to railway engines, finished manufactures to electrical goods, mining and oil drilling equipment, farm machinery to textiles, financial services to food and drink, Scotland has excelled.

For this latest plan the administration has sought input from the enterprise agencies, Scottish Chambers of Commerce, the Fraser of Allander Institute, and the government’s export promotion arm, Scottish Development International. This is set to be refocused on target countries and revamped. So why are we now struggling to maintain momentum? Why does export growth matter so much? Why have previous targets proved so hard to reach? And will the latest strategy prove more successful – or end in further failure?

Performance

Of all the ingredients that make for overall economic performance, a high level of exports ranks high. It means greater market and earnings opportunities for Scottish firms, and a lift to both job opportunities and living standards. The more companies earn through exports, the greater the retained earnings for further investment. And the greater their earnings, the greater the contribution to local and national tax revenues to improve infrastructure and public services.

The raw figures are these: Scotland’s exports in 2017, the latest year for which full figures are available, totalled £81.4bn, up by £4.1bn or 5.2 per cent on the previous year. International exports (excluding oil and gas) grew by £1.9bn, or 6.2 per cent, to £32.4bn. Of this total, exports to the EU, up by 13.3 per cent, accounted for £14.9bn (though this includes exports to the Netherlands, one of our top-five international exports, from where many exports are further shipped to destinations beyond the EU – the ‘Rotterdam effect’). The US remained our top destination country with an estimated £5.5bn of goods sold. Exports to non-EU countries were up 0.8 per cent at £17.6 bn while exports to the rest of the UK totalled £48.9bn, up by £2.2bn or 4.6 per cent.

Much has been written of the woes of the manufacturing sector. But in 2017 our international manufacturing exports performed well, up by 10.3 per cent at £17.6bn, while exports of services increased only slightly, up by 0.6 per cent at £12bn.

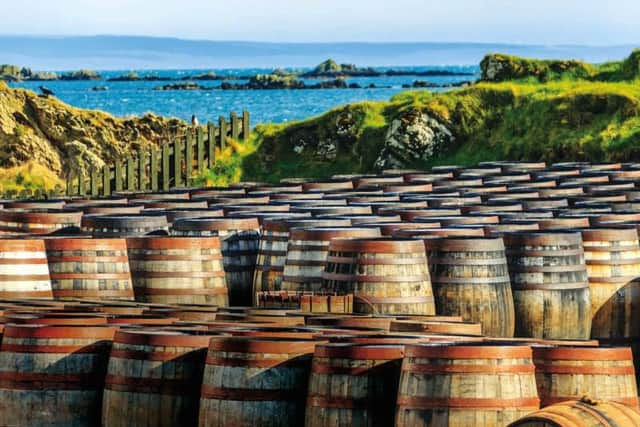

Who are our consistent export winners? Top of the table is the food and drink sector with exports of £5.9bn, accounting for 18 per cent of the international total. Exports from this sector have grown by almost a third since 2010, with the lion’s share provided by whisky which accounted for £4.4bn (74 per cent) in 2017.

Next come professional, scientific and technical services at £3.7bn, helped by financial and insurance activities up by 8.8 per cent to £1.8bn. The third strongest export performer was refined petroleum and chemicals (up 35.6 per cent at £3.5bn).

Priorities

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Trading Nation document focuses resources on countries and sectors which the government deems most likely to deliver the largest, most sustainable contributions to our economic growth. To deliver the growth target, the plan includes £20 million of funding over the next three years, on top of the £85m already provided to support businesses in trade and investment. To target this, the administration has profiled the top-26 export destination countries and calculated an “export value gap” – based on comparisons of Scotland’s current exports with those of similar competitors. For example, with Germany, which accounts for 7.2 per cent of our exports, the export value gap is calculated to be 13.7 per cent.

Exporters to these ‘Priority 1’ markets, representing two-thirds of our exports (US, China, Germany, France and Italy prominent among them), will be supported by an in-market Scottish Development International presence, more trade envoys (the plan cites a possible increase from four to 122), an expansion of GlobalScot from 600 to 2,000 and priority for trade missions and ministerial visits.

Japan, India and Brazil are included in a list of ‘Priority 2’ markets which account for 11 per cent of the export value gap and will be given extra support through trade envoys and close working with the Department for International Trade.

How effective will all this be? Analysis by SPICe cites three reservations. First, it is not clear whether the aim of the strategy is to close the export value gap entirely, or by as yet unspecified amounts. Second, while output goals are set, it is not known what the government expects them to achieve. And third, it is unclear how the additional £20m of funding will be spent.

But these reservations pale before much broader questions, not only about the validity of the export value gap concept but also about the plan overall. Comparison with “countries of similar size” only takes us so far. For example, these may include continental European countries that are geographically closer to Scotland’s ‘Priority 1’ target markets and where transport and logistics costs are lower. Or the comparator countries may have singular areas of resource availability or expertise which account for superior export performance.

A notable feature of Scotland’s business composition is the tens of thousands of small and medium sized companies which until now have had little experience in or resources for negotiating international markets, or indeed the appetite to do so. It is not clear how the new strategy will reach out to these. Then there is the outcome of the current Brexit imbroglio – whether there will be a deal, or no deal, whether we will be in the Customs Union or out of it, a possible further timetable extension or even abandonment of Brexit altogether. A potential convulsive general election and change of government add to this swirling black cloud of uncertainty.

These may be considered temporary political hurdles that have little impact when setting a ten-year target. But they would almost certainly impact on the sterling exchange rate – and that can be a critical factor in our export performance. A higher exchange rate would make our export goods and services relatively more expensive. A lower pound might seem to enhance our export competitiveness. But it would also drive up the cost of imported semi-manufactures and raw materials.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs it is, ten years is a very long time-span for targets of any sort: economies, currencies, technology and politics can shift. The Holyrood administration has pledged to review its strategy as circumstances change. It is a commitment that merits emphasis, for it may well prove the one certain outcome of this monumental Trading Nation document.