Write Stuff: Once a Great Leader by Rodge Glass

To attempt the story of a whole life is an impossible job. Even the most mundane existence will contain a thousand pivotal moments, many of those secret, some of them secret even to the subject and certainly to those close by. Then there are the age-old complications of disagreement, confusion, deceit. Of the witnesses who feel they have been wronged and are out to even scales that only exist in their minds. There is, alas, the essential question of what to leave out, every good biographer knowing that each sensible omission, no matter how innocent, distorts the remaining detail, making it seem larger, as if highlighted in the mind of the reader. And yet more. Following this there is the equally crucial question of whether to present the life in isolation or on a broader canvas – and if so, which canvas? Family? Nation? History? The enterprise is fraught with ambiguity and compromise, and that’s before one gets to the issue of the writer’s bias, which is always, without exception, the greatest variable. In short, the whole thing is an attempt to impose order on chaos. Even the biography of the most habitual hermit, living in the dullest of times, would be a challenge to anyone who values the word “truth”.

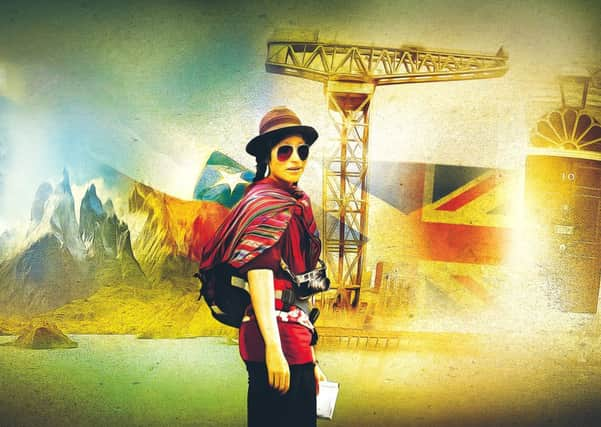

With all this in mind, how should one approach the life of Gabriela Emilia Moya? With trepidation? In fact, should one approach her life at all? This complicated woman was the first immigrant prime minister of Great Britain, an archipelago which has almost exclusively been ruled by the established Eton and Oxbridge elite for centuries. She came from poverty. She was Scottish at a time when Scots were deeply unpopular in England. She was a Republican in a time of Royalists. (Any of these things might have kept her from the top job.) In addition she was the first single mother to climb what she called “that slipperiest of poles, designed by and tailored to men”. And on top of all this, the first female leader of the Labour Party, lagging some five decades behind the supposedly more traditional-minded Tories. Moya was someone who, according Tony Blair, “packed a hundred lives into fifty years”, whose charm many found irresistible, whose eloquence made her if not exactly liked then certainly respected on all sides of parliament and whose unflinching honesty made her unique in political circles. (As we shall see, that honesty eventually compromised her professional life.) What else?

Advertisement

Hide AdShe treated being prime minister as if it were a job like any other, nothing special, an unsavoury business which was indecent to discuss over dinner. Yet in the House of Commons she was spontaneous, she spoke mostly without notes but with a rare passion – as if her most fervent beliefs poured out into the chamber unbidden, clear, poetic, unscripted – a talent some commentators credited to her Latino background, treating it as if it were some kind of witchcraft, somehow not her at all. (Moya fought a lifelong battle against stereotypes, especially those targeted at Latin American females.) And yet, despite the drive which took her to the top of British political life, she embraced retirement as an opportunity to become herself again – or someone entirely new, effortlessly leaving behind her previous identity without a thought, like a snake sheds yesterday’s plates. She outgrew the narrow world of Westminster. Downing Street was a straitjacket she was liberated from just in time. And after that liberation, after the disgrace and the humiliation, despite the torment and confusion of her final year, she acted with rare grace under extraordinary pressure.

To try and tell this woman’s story is at the very least ambitious, at the most, foolish. Or in the words of her elderly father Gustavo, who speaks publicly for the first time in this book, the whole undertaking is “proof of the biographer’s madness”. (I believe that was said with an inward smile.) Well if I’m mad Señor Moya, then I’m sure someone will take me to the madhouse in good time, and as long as there’s a copy of One Hundred Years of Solitude in the library there I won’t complain too loudly at being locked away. But in the meantime I’ve taken great pleasure in putting together the foregoing volume, the first complete account in the English language of a unique symbol of our times, someone who has in recent years been misunderstood, maligned, attacked and all too often ignored. So ignored in her motherland, in fact, that she was able to cross it, for months, without protection, and without being recognised, something I wish to address head on in these pages. This book has eaten ten years of my life, it has led me to the courthouse and the jailhouse, seen me bankrupt more than once and required me to travel the globe in search of the real Gabriela Moya – which is of course, many different people. As I am. As you are. The whole process has been my education; it’s up to readers to decide whether it’s been worth it.

Writing the introduction at the very end of this process, so many of Gabriela Moya’s famous quotations come to mind – my head is brimming with Gabriela, it hums with her sayings day and night, her ghost follows me wherever I go. That’s natural, it’s the biographer’s lot, a profession much maligned but which has brought me succour in the dark days of my own life, paltry as it is in comparison to that of my subject. Still, despite all her famous speeches, it is an anecdote in more private surroundings which I keep returning to at the close of this experience.

When I think of Gabriela Moya, I don’t think of her in her great public highs or tragic lows. No, I think of her shorn of her notoriety, her comforts, travelling her mother country alone, carrying a simple small rucksack and wearing a hat and sunglasses. I think of the nature of her pilgrimage, how she was made of such different ingredients to the so-called “public servants” who spend a lifetime insulating themselves from the people they claim to serve, measuring out their retirements in rounds of golf and evenings on the dinner circuit. In particular I think of Gabriela’s everyday tourist experiences in Chile, especially those early days when she visited the homes of famous national poets and politicians (often the same thing in that narrow “corridor country,” as Roberto Bolaño called it), searching for her soul in the aftermath of her sudden withdrawal from public view, the time when she said she realised she had spent decades “as a tourist in the city of my life”. I think of her waking alone, far from home in the week her daughter Ana-Maria Moya’s debut exhibition, Mother & I opened at the Shoreditch On The Wall Gallery, Ana-Maria refusing to take her calls. I think of her applying make-up in the hotel (as ever, just a splash), eating fruit at the breakfast table while reading Bolaño’s masterpiece 2666 and taking notes, then climbing up one of Valparaiso’s famous steep Cerros, past the statues of the famous Chilean poets in the square, and on just a little further to Pablo Neruda’s house, which is now a popular museum, bookshop and café. This is the day I think of.

She spent three hours in La Sebastiana with her notebook. As recorded in her unfinished memoirs A Guilty Woman Abroad, Gabriela had been greatly looking forward to her visit. After all, her mother had read her Neruda’s nature poetry as a child, and Gabriela had often quoted him in her speeches. (More of this later.) Along with Bolaño, Isabel Allende and the other Gabriela, her namesake Gabriela Mistral, Neruda was, as she put it, “one of the essential Chilean voices who called me over the water”. But excitement fades, and myths often turn out to be just that. The day before, she had devoured Neruda’s biography and was shaken by it, having previously had no knowledge of the poet’s personal life. Now, presented with this museum which made no mention of his Stalinism, his inveterate womanising (a lifelong habit which included an affair with his third wife’s niece), which glazed over the abandonment of his disabled daughter as well as other betrayals, and which indulged his drinking in jokey asides on the audio headset, Gabriela asked to see the manager.

When the woman appeared, she extended her arm to take in the adverts behind her and asked, “Compañera, let me ask you a question. Do you think Don Pablo would recognise himself here?” The manageress waited for this mysterious visitor to speak again, but she stood in defiant silence, her bullet-black pupils questioning the selection of every word on the sanitised plaques, the placement of every vetted household object. Perhaps the manageress recognised Gabriela, thinking she might have seen her on the television? Was she an actress? She didn’t look like an actress. In the background, a video played in one of the museum’s side rooms – Neruda presenting a television programme in the 1960s, the kindly grandfather with a map on his lap, telling the story of his nation like some monochrome ghost deity talking of the land, the Mapuche, the conquistadors. Only Neruda’s voice was audible between the two women, bleeding through the wall. Other visitors turned their heads, sensing something. Eventually, the manageress opened the till, and the ex-prime minister of Great Britain smiled. Then she shook her head, refusing the money. “Gracias, compañera, y buena suerte,” she said, extending her hand for the manageress with a smile. The woman could not give an honest answer to the question, would Don Pablo recognise himself? without risking her job. Moya understood that, and did not expect one – as she famously said at an early party conference, “all women are my sisters,” and she would not humiliate a sister, especially not in public. She was just physically incapable of leaving a lie unchallenged. The two women shook hands, and both walked away, dignity intact.

Advertisement

Hide AdReaders, I don’t claim the following is the definitive life of Gabriela Moya – these long years of study have not made me quite that deluded just yet – besides, no book could do justice to her. However, I do sincerely believe, despite what her unquestioning defenders might say, those who seek to preserve her memory by distorting it, that if Gabriela Moya were alive today, and she walked around the house of this book, looking at the plaques, listening to the audio commentary, touring the bedrooms and looking out from its vistas, I believe she would recognise it as the house of her life. That is my tribute to her. I hope you enjoy the results.

Rodge Glass is an author, editor, academic and critic. His book Alasdair Gray: A Secretary’s Biography (2008) won a Somerset Maugham Award in 2009, his last novel, Bring Me the Head of Ryan Giggs (Serpent’s Tail, 2012) has just been published as Voglio la testa di Ryan Giggs in Italy (66thand2nd, Roma) and his latest, LoveSexTravelMusik: Stories for the EasyJet Generation (Freight, 2013) was nominated for the International Frank O’Connor Award. He is a senior lecturer in creative writing at Edge Hill University in Lancashire, and is currently working on his next novel, Once a Great Leader.