The Write Stuff: Guilty of something

Carl closed the graveyard’s rusty metal gate, breathing hard, lungs aching from the effort of walking. What was it – about half a mile from the hotel? Too fast, he’d gone far too fast for a body that had spent most of a month lying flat and then a week shuffling between rooms.

Crows rasped in the trees as the wind freshened from off the sea. The place reeked of wet earth and rotting leaves. He felt lightheaded, dizzy, the fresh air knifing his lungs. He coughed, hawking a gobbet onto the gravel path that skirted the graveyard.

Advertisement

Hide AdHe soon found Howard’s grave, a fresh mound next to those of the two German tourists. Carl stood for a while, then dropped to his haunches and scooped a handful of earth from Howard’s grave.

An oystercatcher alarm-called as it flew, arrowing level with the dark-rock shoreline. He had come to know the sound of the bird. The soil was cold and sticky in his hand.

‘Sorry,’ he whispered, throwing the handful back onto the pile. His throat tightened. ‘Why did I f***ing listen to you? Why did I let you do it?’ He gasped for breath. ‘Where is everything? What am I doing here?’

Now that the fever had left him, realising where he was and what had happened threatened to blot out every other thought and feeling. Consciousness without purpose was now the dominant state. Never waking up at all would have been better.

Mistakes: to the nth power.

The world was dead, and he had helped kill it, in his own little way. Call it a sin of omission. Carl could add his only friend to the list of the dead while he was at it. There was guilt enough to gorge on, with extra guilt to go. It entered his bloodstream with every breath, all washed down with a cold glass of grief.

He stood for a moment, staring down at the grave. Insects crawled on the rectangular mound of earth. They had a job to do, above and below the ground. Wind stirred the trees again, making them sway and creak. Everything had an appointed function, except him.

Advertisement

Hide AdThere was an obvious destination: somewhere he had to go. As he looked around the bay, judging distances, Carl wondered if he could make it. Going back to where Howard died meant taking one of two routes: he could cross to the south headland, on the main road, before heading inland and into the hills. But that meant going through the main part of the village. Which meant people, and the gauntlet of shock and sympathy. Or he could continue the way he had come, up the back road over the north headland. That way he’d avoid people, but it also took him away from where he needed to go, behind the village, over rough ground, circling around Inverlair and to the south. Call it nine miles of trudging through heather and bogs. That would take him hours, if he managed it at all. With no real conviction, he set off for the hard way.

On the back road up and out of Inverlair Bay, past the church and the community hall and the start of the forestry track, he made it as far as the roadblock, a line of shin-high boulders splashed with red paint. Never mind being at the edge of the world, he couldn’t have gone much further anyway.

Advertisement

Hide AdHe sat on the stones, gasping for breath. To his right, over a rusty barbed-wire fence, fields of rushes and thistles sloped down towards the grey sea. He scanned the horizon for a white boat, for salvation, but saw nothing except the fusing of cloud and water.

Some way off the road was a derelict old house, windowless, with a ragged corrugated-iron roof. To his left, the hills rose to the fissured rocky summit of Ben Bronach, and beyond, to the deer forest. After a few minutes Carl got up and, standing at the roadblock with his hands in his coat pockets, considered the road ahead. He stepped over the painted boulders.

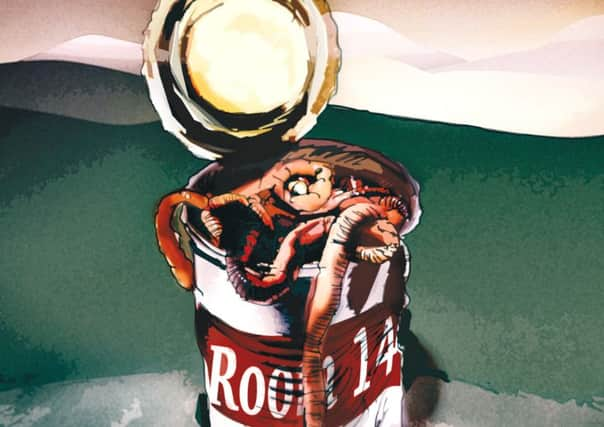

Maybe today was the day when the world would open up again. He could drive away from Inverlair. He could leave Room 14 and Simone and the baby, today, the eighty-second day of his confinement. This would be the last day he’d have to spend here, in this prison refuge. The redzone would open. Its signal would fail.

He took Howard’s deltameter out of his pocket and watched the EMF waveform on the screen, spiking at 85 microtesla today, close to the active neural level. Another hundred metres or so and, he knew, the buzzing sound would start in his head. Another two hundred after that and the pain would skewer through his head, from temple to temple. Any further and sleep was death.

Today was not the day. But he’d known that anyway. There would be no escape. Even before he took his dead friend’s gadget out of his pocket to check the signal he knew what it would tell him.

The next day, he stood in Room 14’s en suite, in front of the mirror. Pits of ash where his eyes had been, thick phlegm-flecked beard and limp coils of oily hair.

Advertisement

Hide AdWith a pair of borrowed scissors he cut his beard to a point where shaving could finish the job. Without hot water it stung and he nicked the skin a few times as he went, hair filling the sink, red drops on the thin scum of soap and grease. Even though the razor was blunt he managed to shave off half his beard, stopping to touch the hairless side of his face, the fever-scooped hollows where his cheeks had been. Two months ago his face had been full and he hadn’t felt like a decrepit wreck of a man.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael F Russell grew up on the Isle of Barra before leaving to study Social Sciences at the University of Glasgow, followed by a postgraduate diploma in Journalism Studies at the University of Strathclyde. He is deputy editor at the West Highland Free Press and his writing has appeared in Gutter, Northwords Now and Fractured West. He lives on Skye with his partner and two children.