The Write Stuff: Confession of an assassin

Scougall sat in the Flanders Coffee House reading the latest pamphlet. There were rumours that the King was to bring Irish troops to pacify Scotland and that William sought to reform the government rather than seeking the crown. If King James did not come to an accommodation, he would take the throne with his wife, Mary, James’s daughter. The people in London did not view an invasion as a Norman Conquest by another William, but as deliverance from the Papist yoke. On the King’s Birthday no guns were fired from the Tower of London. Indeed, the sun was eclipsed at its rising, the signal of the victory of William the Conqueror against Harold at the Battle of Hastings. This was held as a good omen and there was expectation among the people of the arrival of William’s fleet in a matter of days.

He finished his coffee, left the sheet on the table and made his way to MacKenzie’s lodgings in Libberton’s Wynd, an apartment of rooms on the third floor of a tenement just off the High Street.

Advertisement

Hide AdMacKenzie was working in his study. ‘I need to visit a client, Davie. Alexander Stuart, son of the Laird of Mordington.’

‘The assassin, sir?’ Scougall was shocked to hear the name of Kingsfield’s killer.

‘I’ve overseen the family’s affairs for years. His mother is travelling to Edinburgh from the family estates. His father is a soldier on the Continent. I need to see him this morning, but first let’s breakfast.’

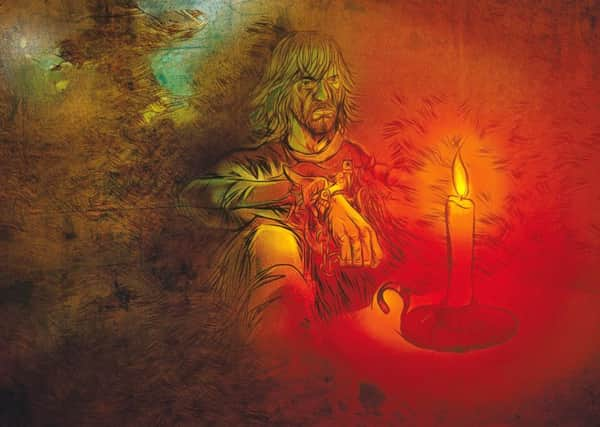

The Tolbooth was an ancient stone conglomeration on the High Street beside St Giles Kirk, a couple of minutes’ walk away. The city councillors met behind its ancient walls, while prisoners languished in its dark cells. They were shown into a stinking windowless chamber lit by a couple of candles where a young man sat at a stained table. He was a few years younger than Scougall, perhaps in his early twenties, dressed in a finely cut but filthy suit. He wore no periwig, so his thin face, bulging blue eyes and shock of fair hair were visible in the flickering candlelight.

MacKenzie asked Scougall to record Stuart’s words in shorthand.

‘Tell us what happened on the sixteenth of October, Alexander?’ he asked.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe young man spoke slowly without emotion. ‘At thirty minutes after ten I rose from my seat in the Royal Coffee House. I walked up the High Street and waited at the entrance of Foster’s Wynd. I cocked my pistol in the shadows, keeping it hidden in my jacket.

‘I had to wait about ten minutes before I saw him walking towards me with his servants. I sauntered down the street, cradling the gun under my coat. When he was about five steps away, I removed it and fired at his heart. God’s work is done, I said to myself.’

Advertisement

Hide AdScougall was disturbed by the cool manner in which he confessed.

‘I provided Mr Stirling with the same statement,’ Stuart continued. ‘I don’t know why my mother has asked you to act on my behalf. I’ve made my confession. Kingsfield deserved to be slain. Now I must die.’

‘There are a few legal matters to tidy up,’ MacKenzie began in a perfunctory tone as he observed him carefully. ‘Why did you do it?’ he asked calmly.

‘The Duke opposed the King’s policy of toleration. He was an enemy of the true Catholic Church. I acted with authority.’

‘Whose authority?’

‘With the highest authority.’

‘God told you to kill Kingsfield in cold blood?’

‘Our King seeks toleration for all his subjects. Kingsfield stood against this. He sought our continued persecution.’

‘Your mother will be here soon, Alexander. She travels north,’ MacKenzie added.

Advertisement

Hide AdScougall wondered what agony she must be experiencing, what disgrace – the conversion of a son to Rome was humiliation for a devoutly Protestant family. Stuart’s father fought against the Papist on the Continent.

‘We’ll have to send word to your father. It’ll be terrible news for him,’ said MacKenzie.

Advertisement

Hide AdHis mention roused Stuart from his lethargy. ‘Do you mean my conversion to the true faith or the slaying of Kingsfield?’ There was a bitter smile on his face.

‘It’ll be terrible news to learn his only son’s to be executed for murder.’

‘My father cares nothing for me. He hates me and I despise him.’ There was finally emotion in his voice. ‘He’s an emissary of the Devil, the darkest rogue. He’s abused us all his days. Now I have revenge!’

‘You committed murder to spite your father?’ asked MacKenzie.

‘I sought to serve God and the true Church. My father is irrelevant.’

‘What did you mean by him abusing you?’

‘I don’t have to answer your questions. I’ve nothing more to say on the matter. I killed Kingsfield. There are a score of witnesses to the slaughter.’

Advertisement

Hide Ad‘How did you know when and where to find him?’ asked Scougall.

‘I was told by God.’

‘Someone must have told you.’

‘I was told by God.’

MacKenzie shook his head. ‘We’ll see to your affairs as your mother requests, pay your debts and collect all that’s due from your debtors. Is there anything else you want from us?’

Advertisement

Hide AdStuart looked down at his hands, gazing at a ring, turning it gently round a skeletal finger. MacKenzie’s eyes were drawn to the large blue gemstone.

‘There’s one thing. I want my final words printed so all may hear the truth.’

‘That will cause trouble, Alexander. It’ll draw attention to the Papists in town when it’s best they lie low,’ said MacKenzie firmly, annoyed by the arrogance of the young fool.

‘We’ve no wish to lie low, sir. We’ve been silent too long, accepting persecution. We’ve put up with the rule of a corrupt church without fighting against it.’

‘You think nothing of your mother, boy?’ There was a flash of anger in MacKenzie’s voice. ‘She’s your flesh and blood. She’ll be left alone with your father… when you are… gone.’

This last word seemed to make Stuart pause for reflection. ‘It can’t be helped. She’ll join me, in time. But I must serve God first. My dying words will be published. I must speak directly to the people of Scotland; tell them they can worship in the way they wish, celebrate the Mass without disturbance or threat of arrest; raise their children in the faith. I believe she’ll understand in the end.’

Advertisement

Hide Ad‘As your legal adviser, I recommend strongly that you don’t have any statement printed. If you’re inclined, make a confession to your friends in a private letter which may be published at a later date. Write to your mother proclaiming your love for her. Don’t have your dying words printed. Only the mob will take sustenance from them. For your mother’s sake…’

‘I serve God, not my mother,’ Stuart said resignedly.

MacKenzie rose from his chair, glowering down at him. ‘Do you understand nothing, boy! You’ll be tortured by the council! You’ll be forced to tell them everything in the end!’

‘God will protect me. I don’t fear torture.’

Advertisement

Hide Ad‘If you don’t give the names of those who helped you, they’ll put you to the Boot or Screw. There’s nothing I can do to stop it. Rosehaugh will argue that the security of the realm is threatened. The government will want the names of all the conspirators.’

‘There are none. There was no conspiracy. I was told by God what I should do.’

It had not occurred to Scougall that Stuart would be tortured. The devices were appalling: the Screw ripped out fingernails; the Boot crushed the leg to pulp. Few did not talk under such agonising assault. He wanted to feel pity for him for the pain he was to suffer. But his arrogance was palpable. He cared nothing for Kingsfield’s kin. He cared nothing for his own mother. He was a foolish Papist who plotted against the Protestant religion. If he was not killed, he would murder again. Papists would destroy everything created since the Reformation.

‘For the last time, I ask you not to publish anything.’ The anger was gone from MacKenzie’s voice.

‘I insist upon it, sir. As my man of business, you’ll attend to it or I’ll employ another.’ Now Stuart’s eyes flashed with anger.

‘You imbecile – you ignorant fool – you’ve had all the benefits of the laird’s life, but you’ve chosen the path of the knave. You’re nothing but a puppet whose strings are pulled by others.’ Then MacKenzie switched to Gaelic: ‘Amadan na mì-thoirt, bhiodh meas duine ghlic air nam biodh e’na thosd. The poor fool would pass for a wise man if he held his tongue.’ The words calmed him, his anger melting to sympathy. ‘I’m sorry for you, Alexander. I’m truly sorry for you. There’s nothing more I can do.’

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Advertisement

Hide AdDouglas Watt is a novelist and historian who lives in Linlithgow with his wife Julie and their three children. He won the Hume Brown Senior Prize in Scottish History in 2008 for The Price of Scotland: Darien, Union and the Wealth of Nations (2007). Pilgrim of Slaughter (Luath Press, £9.99) is the third in his series of ingenious murder mysteries set in 17th-century Scotland featuring lawyers John MacKenzie and David Scougall. The first two in the series are Death of a Chief and Testament of a Witch.