The write stuff: Barn Owl by Jim Crumley

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jim Crumley is a nature writer, journalist and poet with 25 books to his name, mostly on the wildlife and wild landscape of his native Scotland. As a wildlife expert, he is in high demand as a contributor for TV and radio, as well as to publications such as the Scots Magazine and BBC Wildlife. His most recent book, The Eagle’s Way, explores in depth the golden and white-tailed eagles of Scotland. It was published by Saraband in March, and was shortlisted for a Saltire Society Literary Award. This extract is from his new book, Barn Owl, out now and published by Saraband.

I WAS very young when I understood why a heart shape symbolises love. It was the shape of the fair face of barn owls – and I loved barn owls. Prefab childhood in 1950s Dundee was essentially lived more out of doors than in. The prefabs were neatly buttoned to a west-facing hillside along the last street in town, and the farmland of Angus began across the road. Fields were as much for playing in as growing crops. From the top of the highest fields the land fell away northwards and rose again to the promise of the Sidlaw Hills. I considered winter geese and spring and summer skylarks to be as much my neighbours as my fellow prefab-dwellers ever were.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe entrance to the farmyard was no more than a quarter of a mile away from our prefab, but it was forbidden territory, and inhabited by what Lewis Grassic Gibbon would have called “coarse brutes”. Thinking about it now, they must have been simply people who did not know how to get on with the non-farming neighbours surrounding them on three sides. I hid when I saw them coming, though it does me no good to admit it now. One of them, only slightly older than myself, once opened a nasty cut in the side of my leg with an astonishingly well-aimed stone.

But the stackyard was a different proposition from the farmyard. I thought of it as no-man’s land. It belonged to the farm, of course, and farming things happened there, but it was frontier land that lay between the farmyard and the street from which it was only flimsily fenced off. And mine was the kind of childhood that did not pay much heed to flimsy fences.

Haystacks were shifting, unchancy creatures, especially at night. They seemed to appear overnight then stood around for weeks, or months, and grew dishevelled in gales and downpours. Voles, mice and rats and other furry beasts I couldn’t name sped along the curved alleyways between stacks, and barn owls loved voles, mice and rats as much as I loved barn owls, albeit a different kind of love.

So my first barn owls coursed silently through my most impressionable years, low-flying, head-down hunters that tilted and swerved on one wing tipwing tip or the other as the light faded over the Tay estuary far below and the lights of villages on its Fife shore glittered in small clusters. The darker the night, the brighter the face, the breast and the underwings of the moping, mopping-up owl, and the more predatory its grip on my young imagination.

The farm (it seems to me now) was a poor, run-down place with run-down barns, and these are the barn owl’s favourite kind. Any evening I happened to be walking home that way (and always just a little heart-in-mouth at the proximity of the forbidden territory), there was always the chance of meeting head-on and at close quarters the fair, heart-shaped face of the haunter of no-man’s land.

These were encounters with nature at the edge of things, the edge of the day and night and the edge of my comfort zone, beyond which the black outline of the farm buildings bleakly inked in my discomfort zone.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe barn owl is an ambassador for life on the edge. It is the night owl that also hunts fearlessly by day; the silent flier with a sudden shriek that can shatter glass (and in the brain of a short-tailed field vole it must sound like the shrill anthem of death itself); the restless sentry of the outside edge of the woods with one ear attuned to the grassy banks and the other to the first and last tree shadows; the stone-still embellishment on a country kirkyard gravestone beyond the edge of the village, looking in moonlight like nothing so much as the sculptor’s final inspired flourish.

Those childhood barn owl experiences survive only as a patchwork of memories, memories of glimpses, as unrevealing as moths darting in from the darkness to dance at a flame and vanish again. I remember nothing other than impressions of a few seconds of flight at a time, usually into the insipid glow of street lights, then fading away into the gloom, always fading away into that other world where owl and farmyard conspired to do whatever it was they did together. Except once.

Advertisement

Hide AdThat once was when I was lured by forces beyond my control across no-man’s land and into hostile territory, the forbidden world beyond the haystacks. It was the first time I ever saw the owl fly in daylight. It was a sunny early morning of spring – although why I might have been near the farm in early morning escapes me now. The owl had appeared among the stacks with its beak clamped round a mouse that hung down from its heart-shaped face like a moustache (a mouse-tache), and I had not seen that before either. It flew away round the corner of the nearest building, vanished, then reappeared a few seconds later, spotlit by the sun against the dark background of a second building on the far side of the farmyard. I had never so much as looked at that building before, but now I saw that its door leaned open at an odd angle and that through the doorway I could see gaps in the slate roof. The owl banked left and flew inside. This was new intelligence. An owl that lived inside a building was not a possibility that had ever occurred to me before.

Moments later it was out again, and clean-shaven (the mouse-tache had gone). Even at that tender age I understood nests and had found skylark, blackbird, chaffinch and robin nests within half a mile of home; sparrow nests in the garden hedge. And I knew that kittiwakes (already one of my favourite words) nested on sea cliffs out by Arbroath. I understood something of how they worked, but they were all outside, in the grass, the bushes, the hedges, or staring out to sea. I was still coming to terms with the problem of a bird that lived in a building when a second barn owl flew out from the broken-down door of the broken-down barn.

My first thought was that it might be a brother, because I had one, and we were accustomed to going in and out of a building by the same door. Then an owl flew back in. The same owl? The first owl? Another owl altogether? How many owls were in there and why was the building so important to them? Before I knew what was happening (and years before I understood what was happening), I was in among the haystacks and heading for the corner of the nearest farm building. I flattened against the wall (I had seen people do this in films) and peered tentatively round the corner. Coast clear (I had heard people say this in films). I inched sideways along the gable end to the next corner where it suddenly became clear that I was deep in forbidden territory, and that between me and the owl door of the owl building was a wide open space deeply rutted with mud and liberally dowsed with cows**t, which at the time I would have politely called “country pancakes”. Almost certainly, I would have been wearing Clark’s sandals, short socks and short trousers. I was not dressed for this.

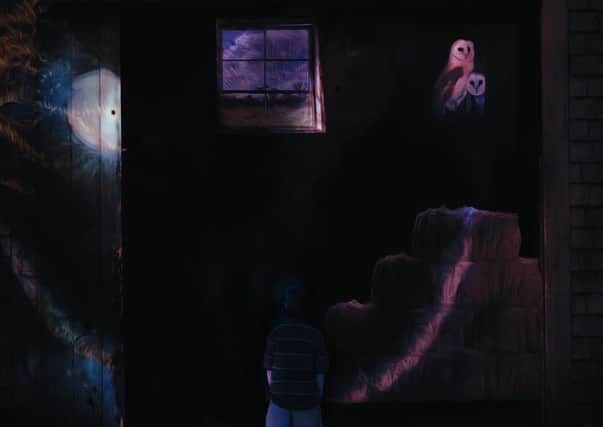

If there had been people moving around, if there had been tractors, horses, herds of cows, or any one of the awful tribe of coarse, stone-throwing brutes, I would have lost my nerve and run. But there was no-one and nothing moving. The smell was what troubled me most at that moment, but a bad smell was no worse than a flimsy fence. I ran across the farmyard and straight in the door of the barn. It was almost underworld-black in there after the sunlit overworld where glowing birds with white, heart-shaped faces flew. At first, all was shadow, gloom, chaos, I bumped into things, then something muttered from somewhere up near the roof. I looked up into a white, heart-shaped face, and in that moment, the barn owl claimed me as a friend for life.

It tilted its head at right angles, so that the heart-shaped face looked like a butterfly, then straightened up again. It was, I decided, a conjuring trick. It was, unquestionably, magic.

The owl was standing on a kind of wooden shelf where the wall met the roof. Right next to where it stood was a curious low pile of grey stuff that looked like a cross between wool and used Brillo pads. It would take years before I realised what it was and what it was made of.

Advertisement

Hide AdThen a second owl drifted past me somewhere near the floor and rose without a sound to the same shelf and stood beside the first owl, then both birds did the sideways head trick again, and I wanted to clap. Then the second owl sat on the pile of grey stuff. Then a tractor engine fired up in the distance and my awareness of where I was and what I was doing and what would happen to me if I was caught rushed in the door like an icy wind. The owl-spell was shattered and I had wings on my feet. I was over the fence and most of the way home before I stopped running.

“I fell in the field,” I explained to my mother as she first looked at me then caught the scent of cows. But something fundamental took root that day and I reap its consequences still. I had charged into no-man’s land, crossed enemy lines, lived to tell the tale and returned a warrior for nature’s cause. Barn owls did that.

The prefabs, the farmyard, the stackyard and all the fields have long since been obliterated by housing and a major hospital. The barn owls retreated beyond the redefined boundaries of suburbia.