Why Scotland’s theatres must work together if they are to survive Covid-19

There’s nothing fair, or even entirely comprehensible, about the uneven impact of the Covid-19 crisis on our society; but one thing of which we can be sure, as the drama plays itself out, is that this virus might have been designed to rock the foundations of live entertainment as we knew it. Given the nature of the infection, and the way it is primarily transmitted, the pandemic simply precludes the holding of normal theatre or live music events. It wrecks the economic basis of those industries, since a socially distanced audience is inevitably a very small audience; and even more significantly, it removes their most important social function, which is to bring people close together in a heightened shared experience that enables us to feel, with all our senses, the sheer joy of being part of something larger than ourselves.

It’s not, of course, that we will never be able to gather in packed audiences again; that day will come, although possibly not until next year. In the intervening months, though, many theatres and music venues may be forced to close for good. Already, major London theatres – led by West End producers Sonia Friedman and Nica Burns, and National Theatre director Rufus Norris – have told the UK government that they simply will not have a theatre industry by early 2021, unless they step in with a massive support package.

Advertisement

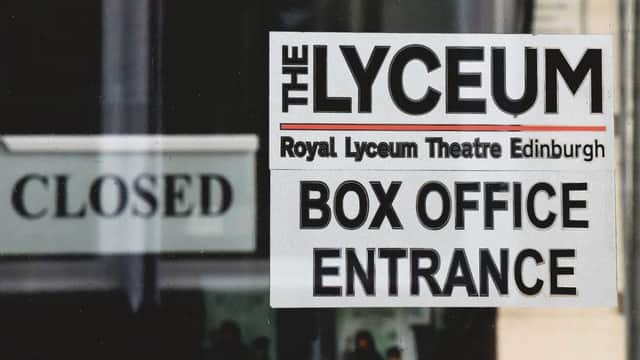

Hide AdAnd here in Scotland, a similar crunch-point is approaching, at alarming speed. Last Thursday, Edinburgh’s Lyceum Theatre, by some measures Scotland’s premier producing theatre, issued a momentous press release putting its beautiful building in Grindlay Street into mothballs until Spring 2021, and issuing a notice of possible redundancy to all of its staff.

As has been the way with this capricious virus, the Lyceum is particularly hard hit because it is relatively commercially successful, with a high dependence on box office income, and public subsidy forming only 15 per cent of its turnover; Pitlochry Festival Theatre and Eden Court in Inverness are in the same position, as will be the public trusts that run Edinburgh’s Festival and King’s Theatres, and Aberdeen Performing Arts. And with the Scottish government suggesting that social distancing rules will probably be in place until the end of the year, other theatres are likely to make similar announcements soon, raising questions about whether the whole infrastructure of professional theatre-making and performance in Scotland, painstakingly built up in the 75 years since the Second World War, can survive this crisis – and if so, in what form.

“Right from the start, I think there has been a very grown-up recognition, across our community, of the sheer scale of this crisis, and of the fact that it is going to bring change,” says Liam Sinclair, joint chief executive of Dundee Rep Theatre, and currently co-chair of the Federation of Scottish Theatre, which brings together companies, venues and artists across Scotland. “Undoubtedly, at the end of this, some familiar features of our cultural landscape will no longer be there; and the question is whether we can work out a common strategy for sustaining Scotland’s theatre community through this, and for restarting next year on a basis that’s viable, and that still works for our audiences, and for the artists and other professionals. One of the most encouraging aspects of the crisis so far is that we do have a huge amount of support from audiences; so far, more than 50 per cent of those who had bought tickets for cancelled shows or seasons in Scotland have donated the money, or accepted vouchers instead of a refund.”

There’s no doubt, though, that substantial government backing will also be needed to support Scottish theatre through this crisis, and to ensure that most of the building-based companies, in particular, are still with us come next year.

“We are already talking to the Culture Secretary, Fiona Hyslop, and others,” says Sinclair, “but we are aware that this is a different situation from the one in London, where the West End is a huge commercial attraction, and we’re not simply asking for money without any conversation about how it is used, and how the future looks. Even in lockdown, we’ve already shown that we are a community of entrepreneurs and problem-solvers, and that we still have a great deal to offer through online initiatives, and through using our skills in new ways. Our wardrobe mistress at Dundee Rep, for example, has been co-ordinating a huge team of people, all making scrubs at home for the NHS in Tayside.

“There are also suggestions about how the theatre buildings themselves could be used, while they remain closed for performance – for example, could they help take some of the strain off school and college buildings, as they seek to reopen with social distancing in place? Our buildings are very much at the heart of communities in Scotland, and we’d like to find ways of getting through the crisis that reflect that. And we’re also trying to put together a vision for a collective reopening season of Scottish theatre, next year, that will reflect our whole industry at its very best – that could be really thrilling, and make a brilliant statement about what we’ve achieved in the past, and what we have to offer in the future.”

Advertisement

Hide AdFor now, though, the main task that falls to the Federation of Scottish Theatre is to try to keep the Scottish theatre community united, while each organisation fights its own distinctive battles; and to make sure – as playwright Peter Arnott argued in The Scotsman last week – that they have a common strategy, and an argument for survival, that enables them to speak to government and society with one voice.

“Peter’s arguments are certainly music to my ears,” says Sinclair, “because there is simply no way that each theatre organisation can firefight this crisis alone. Just for a start, we all depend on the same community of freelance workers – writers, actors, technicians, designers, musicians – who are themselves struggling for survival as individuals at the moment, with no government support beyond June; and if they are forced out of the industry, we can’t make the shows we want. So we have to act as a community, and to be both realistic and visionary about where we might be, this time next year; and although that’s hard, I think if government steps towards us now, and shows its support for what we’re trying to do, then we can get there – and maybe make a Scottish theatre culture that’s better and more accessible than ever before, given all that we’ve learned in this crisis.”