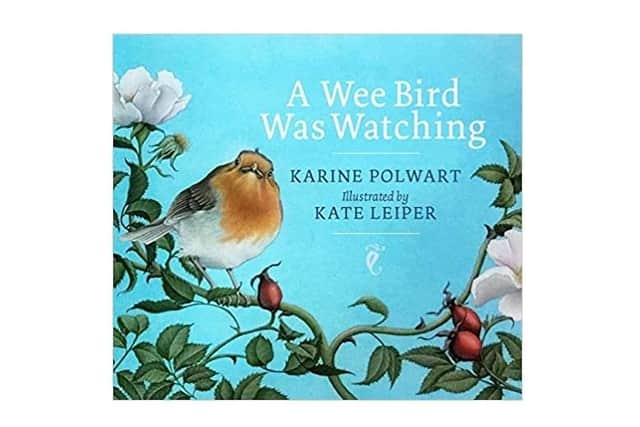

Lyceum Christmas Tales #7: A Wee Bird Was Watching, by Karine Polwart

Anna and her mum had been walking all day. And the whole day before. And the day before that. It was a long time since they’d slept in their own beds. And they were sleepy and hungry and cold.

Let’s stop here for the night and rest, said Anna’s mum.

We can build a fire to keep us warm.

They gathered in birch bark and bracken, dried leaves and twigs and stacked them into a pile.

A wee bird was watching.

Advertisement

Hide AdAnna’s mum took her Firestone from her bag. She struck it over and over until a spark jumped into the bark and leaves. Anna blew gently into the fire until it caught hold.

Anna’s mum pulled a blanket from her bag and tucked her daughter in beside the fire. I’m away to find us something to eat, Anna, she whispered. Stay safe right here until I get back.

And then she disappeared into the trees.

The wood uttered strange sounds. Whoops and whistles. Creaks and rustles.

Anna’s mum plucked brambles from the bushes, and dropped them into her bag. And then she pushed further into the darkening woods.

Anna stared at the flickering campfire until her eyes closed. She didn't hear the crinkling of leaves, the crunching of twigs, as a wolf crept into the clearing.

But a wee bird was watching.

Juicy apples, freshly fallen from the boughs. Anna’s mum scooped a dozen of them into her bag. But they’d need more to eat than that.

Snap. Crack. Snuffle. The wolf crept in, closer and closer.

Advertisement

Hide AdAnna slept on. And the campfire beside her grew smaller and weaker.

But a wee bird was watching.

THE AUTHOR

Karine Polwart writes…

Note: Karine Polwart's Wind Resistance was the first full run show at the Lyceum to be cancelled due to Covid-19. The following was written in April, when uncertainty over lockdown was at its peak.

Advertisement

Hide AdI should’ve been there with you that first lockdown week. In a parallel world, on March 23rd, a small tech team assembles the spartan set of Wind Resistance: test-tubes and vials, a mortar and pestle, bog cotton, prayer bowls and paper birds.

In this alternate world, a dawn chorus rises over a scrap of Midlothian peatbog. Larks in the clear air sing. A skein of pink-footed geese steps up and falls back. Mothers, midwives, and surgeons labour and rest. Barn owls screech. Hawks hover in hospital corridors, white coats and stethoscopes, muttering, muttering, muttering.

And, through it all, a moorcock craiking –

go back, go back, go back.

Go back to what?

Go back to where?

Do you know what? Do you know where?

As lockdown approached, I foraged for our own essentials. Red lentils, because the game’s an absolute bogey without my granny’s soup. A secret Haribo stash for shit days, which has been a priceless investment. And, from Pentland Plants in Loanhead, just in the nick of time, a wee birdfeeder and a big bag of sunflower seed.

My daughter Rosa kept a logbook those first few weeks. She’d sit at the back door, pencil poised, breath held, bird guide open, learning to recognise the 18 species I reckoned would arrive in the garden. Blue Tits. Blackbirds. Robins. Dunnocks. Starlings. Jackdaws. Wrens. But when the goldfinches came, for the very first time, the list was scuppered, an offense to her meticulous alphabetical system. And then, for goodness sake, greenfinches too. Mum! Where am I supposed to write that? But what a delight it was. What a beacon it is, even still.

In plague times, the doctors often dressed as strange birds. Bespectacled corvid masks, beaks stuffed with lavender or cloves. Waxed leather frock coats and wide brimmed black hats. White gloves and long staffs to poke infected bodies. Swords. And shields. No worse, to be frank, than iPhone evidence of Sellotape and bin bags, Scuba masks and catering aprons.

Yet these are, we’re told, unprecedented times.

Your Grindlay Street doors closed six days before the UK Government decree. The whole week before that, I was terrified of you. That might sound overly dramatic. But the fear that I might be contractually obliged to turn up and perform, according to the laws of economy, industry and force majeur insurance, or, worse still, caught in some twisted face-off between your needs, the needs of those beautiful human bodies whose craft and industry keeps you alive, and my needs, my visceral concern for the wellbeing of my family, my crew, my audiences. This kept me up at night in those early pandemic days. And when sleep came, it was choked with airduct spittle, and pathogen droplets spluttered across your velveteen stalls. I woke up shaking, and despite the devastation to my own personal finances, I longed for the cancellation call.

Advertisement

Hide AdWhen you’ve been afraid of something, or someone, even once, the air tastes different. I worry about that.

I’ve carried the image of an avian plague mask in my head, since Primary 4. I drew one on the cover of my special school project that year. It was called simply The Black Death, a leftfield subject matter for an 8-year old girl. I copied the image from a book in the big Stirling library, where the local archivist dug out historic city records for me. I dare say it sounds like I’m making that up. But, for reasons connected to 1970s telly programmes and public health adverts that triggered nightmares, I knew the Infectious Diseases subsection of the Pears Cyclopedia inside out. I could’ve diagnosed a case of Rabies or Yellow Fever in a second.

Even as a child, I tried to counter fear with facts.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe archivist talked me through the 17th century morbidity statistics for Stirling, and I copied them neatly in pencil onto lined fullscap. Rickets. Smallpox. Lockjaw. Teeth. Childbirth. Stillbirth. Fright. Grief. My daughter’s propensity for tables and lists hasn’t fallen from the sky. Two causes of death towered above all others:

Consumption. We call that TB now, my mum explained. And I knew about TB. It was the reason me and my wee brother had those funny white marks on our shoulders. The BCG. I knew that TB had killed my Grampa Peter’s wee sister Tess, and his only brother, Jim, decades before I was born. But my Grampa had survived it. And weren’t we the lucky ones.

Even consumption couldn’t hold a candle to the Plague. The numbers were, are beyond comprehension.

The history of pandemics is written in the fundament of this beautiful city. Did you know, in 1498, all taverns and schools in Edinburgh were closed during an outbreak? Archaeologists have uncovered mass unmarked plague graves on Constitution Street, Leith Links, and the Burgh Muir at Brunstfield. And not ten minutes from where you stand, Mary King’s Close is the nether end of quarantine become light entertainment for the masses.

Yet, these are, we’re told, unprecedented times.

Perhaps, we’re simply wired as humans to forget this scale of suffering and death, in order to keep going, in order to move on. Or perhaps, it’s a cultural disease of its own, this systemic erasure. I don’t know. But there are already forces at work. Institutional reframing. Contested accounting. Shifting patterns of agency and blame.

In 1670, surgeon-naturalists Dr Robert Sibbald and Dr Andrew Balfour founded a New Physic Garden on a tiny plot of land next to Holyrood Abbey. It was a direct response to the city-wide devastation of the plague of 1645 (and by the by, the Great Plague of 1665/66, which ravaged London, didn’t reach Scotland because of nationwide trade blocks and quarantine measures instituted by the Scottish Government). A core aim of the New Physic Garden was to collect, document, and cultivate medicinal plants, from Scotland and overseas, and ultimately to protect the public from the exploitative pseudo-medical quackery of the plague era. It was a garden conceived of as a public health resource. That New Physic Garden is now the Royal Botanic Garden. Closed until who knows when, just as you are.

Advertisement

Hide AdYou’re amongst the institutional pillars of this city, aren’t you? The Botanics and The Lyceum. Princes Street Gardens and The Playhouse. The Meadows and The Usher Hall. The padlocked gates of The Botanics aside, this city’s gardens and parks are alive with people, and never in living memory more alive with blue tits, blackbirds, robins, dunnocks, starlings, jackdaws, wrens.

The buildings are not.

A virus, we learn, is not alive. Or, at least, it bothers the edges of what life is. The bubonic plague that scoured Edinburgh had its own independent existence as a bacillus. It was alive not only as it passed from animal to human, and person to person. But as it stowed away in cloth creases, hibernated in letter folds, and convoyed itself via profit and need, ignorance and ill luck, poverty and love.

Advertisement

Hide AdBut this, this thing that we can’t see between us, it’s not even alive.

And you, a theatre de-peopled, you and all the other spaces in which bodies might gather, listen, sing, how is that you are alive? And for how long? I worry about that.

These are unprecedented times. For us. For you.

My Rosa is in Primary 5, if that’s still meaningful in a household that can’t navigate online home learning to save itself. I’m mindful of just how childhood images stick. An avian plague mask. A nurse in PPE.

Most days, we walk past the shuttered school and on to the fields of rape. There are swallows, yellowhammers, skylarks, crows. And in amongst the grasses, the moorcocks craiking: go back, go back, go back

Go back to what?

Go back to where?

Today me and Rosa will set out more seed. And we’ll sit with the back door open. And maybe, if we’re lucky, the goldfinches will come.

I wish you well. Until next time, Karine

A message from the Editor

Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe dramatic events of 2020 are having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive. We are now more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription to support our journalism.

To subscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app, visit https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions

Joy Yates, Editorial Director