Joyce McMillan: Treasure GSA, but let it live

Phil and his mate Spanky work in the paint-grinding workshop or “slab room” of a huge carpet factory loosely based on Stoddart’s of Paisley, where Byrne himself once worked. One of the play’s running sub-plots, though, concerns Phil’s efforts to get himself out of the slab, and into Glasgow School of Art. His portfolio is stashed behind a work-bench throughout; and in the play’s great final scene, he famously cartwheels off stage, reminding Spanky that “Giotto used to be a slab boy!”

There’s probably no piece of writing, anywhere, that more perfectly captures the texture of the relationship between the people of Scotland and Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s great School of Art, which came so close to being destroyed by fire last week. Beautiful and magical yet also somehow familiar, in the middle years of the 20th century the art school became a gateway through which thousands of students from ordinary Scottish homes – Byrne among them – could pass into a wider world of creativity and thought, and into a global community of makers and shapers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAnd as the process of reclaiming and restoring this great building begins, it’s worth remembering that although its importance to the world of visual art is incalculable, the shock-waves of its near-destruction reverberated across the whole spectrum of Scottish life, and deep into the world of contemporary Scottish theatre, which without Glasgow School of Art would barely exist in its present form.

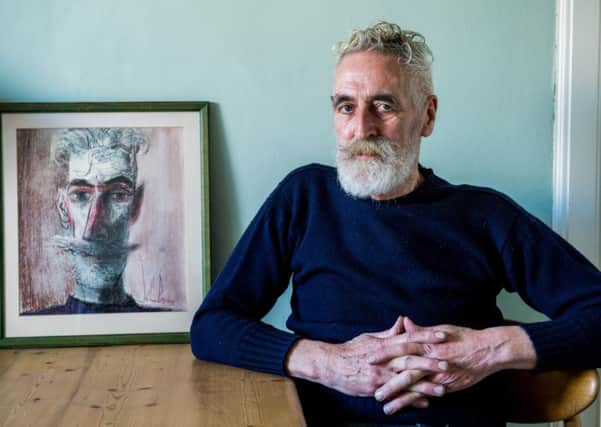

Two of our greatest and most influential living playwrights, John Byrne and Liz Lochhead, were educated there; Byrne still sees painting as his first and greatest vocation, and Lochhead has said that she doubts whether she would ever have become a writer if she had followed the more obvious path of studying English at university. Something about the art school set her creativity free, she says; and a glance over the roll-call of art school graduates shows that Byrne and Lochhead are not alone in moving on into other art-forms, as the names of writers like Alasdair Gray, actors like Robbie Coltrane and Peter Capaldi, and whole squads of musicians and theatrical designers flit past.

There are, in other words, some vital truths we can learn from the remarkable story of Mackintosh’s School of Art. First, that creativity is indivisible. Learning the disciplines and skills of a specific art-form is vital to a young artist’s development; but once that grounding is there, there is no knowing where their creative impulse may lead them. Secondly, that when we use our resources to create a great arts institution, we do it not so that we can achieve predetermined results or “outcomes”, but precisely because we know that a living society needs the capacity to move in directions never thought of before; the careers of Byrne and Lochhead show that the unpredictability is the whole point.

And finally, that when we have an institution as beautiful and remarkable as Glasgow School of Art, we have to find clever ways of treasuring it, while allowing it still to live and breathe and take risks. In her poem to Charles Rennie Mackintosh, written for the School of Art’s centenary in 2009, Lochhead wrote: “A plain wonder of a building’s what you gave to us. / Volume, light, line, astonishing rhythms of space... a great place/ To work in, learn in, live in, take for granted.”

Glasgow School of Art is one great building that may never quite be taken for granted again, after last week’s events. Yet as a place to work in, learn in, live in, it must always be more about creation than preservation; and about that brilliant, unpredictable energy of making and shaping that transforms whole cultural landscapes, here in Scotland, and far beyond.