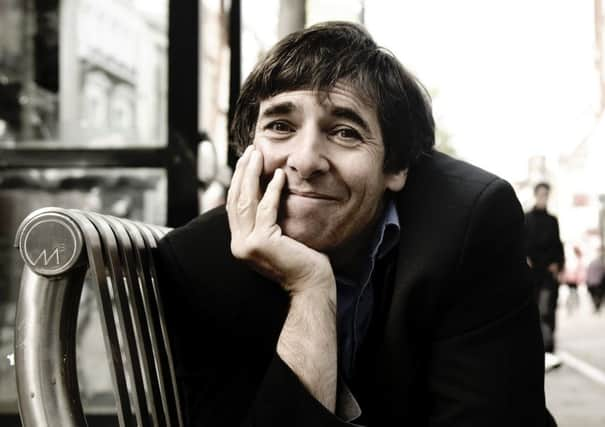

Interview: Mark Steel on his Edinburgh Fringe show

I’m meeting Mark Steel at a cafe in Brighton.“So you live in Brighton now?” I say. “I do seem to live in Brighton, yes,” says the comedian, activist, columnist of the year and creator of the Radio 4 series Mark Steel’s in Town.

The hesitation and vagueness stems from his well-known attachment to South London, where he spends part of each week.

Advertisement

Hide AdCrystal Palace wasn’t his original home but the one he adopted for himself. Steel grew up in Kent. And the parents he grew up with were not his original parents but the ones who adopted him - which is what his Edinburgh show is about.

‘Who Do I Think I Am?’ – tells how Steel discovered he did not have the genes, the nationality or the social class he was expecting. He is, it turns out, half-Scottish, half-Jewish; the child of a teenage runaway and an international jetsetter.

“The reason for doing the show is it appears to me to be a really fascinating story. But it is interesting in the same way it would be to hear about someone else or to read in a Dickens novel. But like all really good stories it asks questions - and I think it answers some of them.”

It didn’t even cross his mind to search for his birth mother until he was in his thirties and had his own first child.

“Then it occurred to me that maybe this woman might remember having me.”

He’s very thankful to his adoptive parents for being open.

“I think that is why it’s never bothered me. When I was a kid people used to say: ‘Doesn’t he look like his dad?’ And my mum used to say: ‘I don’t know why because he’s adopted.’

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I remember knowing I was adopted before I knew where babies came from. And I’m grateful for that. Secrets and lies, that’s what does the damage.”

After his son Elliot was born, Steel began looking into the story of his own birth.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Realising I was born in North London was the most upsetting thing for me. As someone who has trained each of my children to go ‘South London, La La La’ whenever we cross over the bridge.

“I was born in North London. And my mother’s family were all there. They were all on the electoral register and then they all disappeared. All of them. At the same time.

“There were years of sending off tedious letters then waiting for nine months for something to come back.

“Then it turned out they were in bloody Scotland which has its own different set of records. I’d been looking in Burundi, Tanzania and the South Pole and they were just up the road.”

His mother’s family lived in Dunkeld but his mother had moved to Rimini.

In 2009 one of the agencies searching on behalf of Steel got hold of his mother’s number in Italy and called her. “She was very cross that anyone had got in touch with her. She said: ‘You don’t know the pressure I was under at the time.’ Then she said: ‘I have three questions.’

Advertisement

Hide Ad“The three questions were: ‘1 What did I do? 2 Had I got any kids? 3 What were my politics?’”

The researcher told Steel: “I have been doing this 30 years and no one ever asked that before.”

Advertisement

Hide AdOut of the blue his mother said: “‘Let me tell you the name of the father.’ She blurted out the name and put down the phone.”

I ask if he was upset when his natural mother had no wish to meet him. He shrugs his shoulders.

“I thought it was a bit rude after I’d gone to all that trouble. But I get more annoyed when someone on Twitter says: ‘I saw your show and it was shit.’”

He is determined not to be sentimental about his story.

“If you believe the EastEnders version, the soap operas and the films then there should have been a big kerfuffle.

“But it wasn’t like that.

“I just thought it would be nice to see me and to say to me: ‘I have got a genetic illness that makes you catch fire when you get to 60.’”

A few years later Steel went on a weekend trip to see where his mother grew up. “I went to this pretty town of Dunkeld, which is in one of the more conservative areas of Scotland and I go into the cafe my mother owned and the woman behind the counter said: ‘Oh. She lives in Italy now but her sister lives at the bottom of the road.’

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I knocked on the door and said: ‘There is not an easy way to say this but I think we are related’. And she said: ‘Ooooh, oooh. You are the son that was lost and you’re back. Come in and I’ll put the kettle on. I knew there was a wee boy.’”

Steel’s aunt and uncle in Dunkeld turned out to be political activists. “One of them lived in a little cottage and on the beautiful gate was a big poster saying: ‘March to Stop the Tory Cuts.’”

Advertisement

Hide AdAlthough he knew the name of his father, he was proving hard to find.

“Everybody else was more interested in it than me. I’d be talking to a friend and they would disappear and say: ‘I’ve just looked on the internet’. I’d think: ‘I’ve been looking for the last 12 years. Do you really think you are going to find something on Google?’”

For years Steel believed his father was French.

“I got some paperwork through with an interview with my mum, which said: ‘the girl says the father was French.’

“I’m sure there are some people who would say: ‘That’s why he wrote a book about the French Revolution’...or... ‘that’s why he likes garlic and shrugs his shoulders a lot.’ And if they thought that, they were talking shit. Because I’m no more French than Mao Tse Tung.”

Some detective work by his wife Natasha finally revealed the truth.

Mark Steel’s natural father was a Sephardic Jew from a family that had moved to Egypt, then to England then to America. A Wall Street multimillionaire, friend of the royal family and financier to the super-rich, he had been a World Backgammon Champion in the 1970s and had written a book called Backgammon for Profit.

Advertisement

Hide AdSteel got in touch with a couple of friends who “moved in those sort of circles”, found an address and wrote a letter. “I had to be careful and explain I wasn’t being like some 15th century bastard son of the Duke of Monmouth saying I want one of your castles.”

A year later they met up in London and had a row about cricket. It wasn’t a big deal.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Every time this issue is dealt with, whether it’s a real life story, a soap opera or something like ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’, it always involves a load of tears, angst and anxiety.

“I can understand that and if people have that and it’s real then that’s fine but it hasn’t been like that for me.”

However he was moved to realise what his natural mother and his adoptive mother went through in the months after his birth.

His mother, beautiful, 19 and pregnant hid in north London. The adoption was arranged privately through a neighbour and baby Mark was taken home to Kent when he was just days old. But for a year afterwards his birth mother refused to co-operate.

“My adoptive mum told me that she woke up every morning and thought ‘they are going to take my baby away’. And every morning my birth mother would have been thinking ‘I want to get my baby back.’”

The adoption paper, when it finally arrived, had been torn into tiny pieces and sellotaped back together. It said: ‘The mother has now realised it is not practical with no means of support for her to keep the baby.’

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I think that is chilling. ‘The mother has now realised...’ It is like someone who has been accused in a Stalinist Trial. ‘The defendant has now realised...’

“She realised there was f**k all she could do with no support.”

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Today these things happen and people get through them. But back in those times, the 1960s, you must have had women who got pregnant crying themselves sick for years and years because they weren’t allowed to mention it.

“Those are the times people want to get back to according to the Daily Mail, where everybody pretends there is a normal family that we have to have to protect. It’s a lie.”

It is where the personal touches the political that Steel’s distinct comic voice comes into its own. One of his favourite episodes of his recent Radio 4 series was recorded in Paisley – where he celebrated the gung-ho style of the town’s SNP MP Mhairi Black.

“She’s 20 years old but she’s a proper 20-year-old and she’s from Paisley and she’s proper Paisley. I hope the SNP don’t make the mistake of trying to talk her out of that.”

Steel, who first came to the Fringe in 1984 with Rory Bremner and Jenny Éclair, and in 1985 with Paul Merton, is sharing a flat this year with his nineteen-year-old son Elliot Steel, also a comedian.

How is it being a two comic household?

“It’s a disaster because the little sod is going to end up being funnier than me, getting bigger audiences and being richer than me.”

Advertisement

Hide AdHe says people have a misguided notion about alternative comedy in the eighties.

“There are articles and books written that say it was a really political movement but that was rubbish. Most of the time you got up after a juggler, then someone else that would stand up and shout. Then someone would come out and melt a block of ice with a bunsen burner.”

Advertisement

Hide AdFirst and foremost, Steel is a comic, whose job is to make people laugh. The highly personal subject matter of his Fringe show will not change that.

“Of course there is emotion in the story. But there has always been emotion in stand-up. It is an indication of how low the status of stand-up comedy is in this country that comics are persistently asked questions about whether you can do serious subjects in comedy.

“It is absolutely infuriating. Of course you can do serious subjects in comedy – in fact it is much harder to do trivial subjects.

“It is like saying to a songwriter that songs are supposed to be jolly. No one would ever say that to an American comic.”

Whatever the topic Steel’s extraordinary comic brain will always find the funny.

I mention the writer Christopher Hitchens also discovered he was half-Jewish in his fifties and that Martin Amis was envious.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Well I hope he is jealous of me. I love that idea of Martin Amis, sitting in his fantastic apartment, writing incomprehensible sentences and being jealous of me.”

And with that he throws back his head and laughs.

• Mark Steel: Who do I think I am? is at Assembly George Square Studios from 5-30 August (Not Mon 17) at 8.15pm. For tickets £14 (£13) see www.edfringe.com