Stories of Scottish island life captured by David MacBrayne ferries

The characters and way of life which so defined a disappearing generation of Scots islanders and coastal communities is indelibly forged in its story. This is the iconic Scottish ferry firm whose captains would be treated like “pop stars” in the far flung towns and villages where they provided lifeline links. David MacBrayne, forerunner of CalMac, was an institution at the heart of island life on Scotland’s West Coast for the best part of a century.

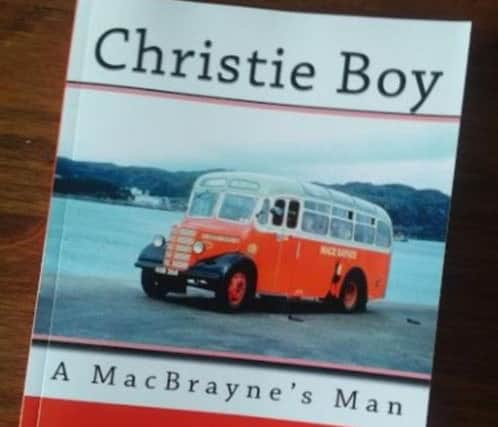

And now many lost tales and vignettes of its halcyon days have been saved for posterity with a new book. Christie Boy – A MacBrayne’s Man is the life story of the late company stalwart Chris Fraser, which offers a peek below decks at some of the hairier moments of the firm’s history. And far from a prosaic record of three decades on the waves, this is a soul-stirring elegy to a forgotten Highland way of life, festooned with a colourful array of West Coast characters.

Advertisement

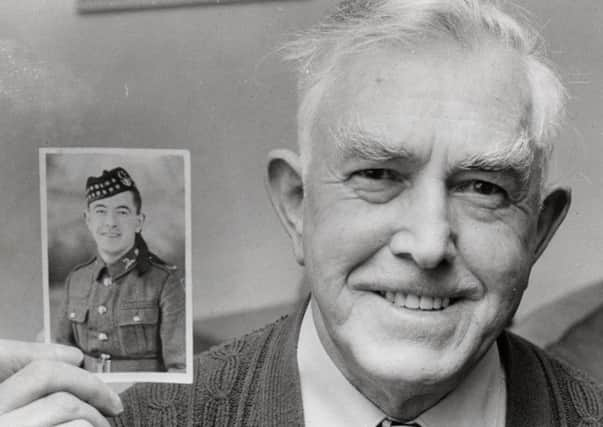

Hide AdFrom starting out in 1928 as a manifest clerk on the Mallaig and Portree steamer, the Glencoe, to his ascent up the managerial ranks in the 1960s, serving across the North West from Inverness and Lochboisdale, Fraser’s story has been revisited and revised by son Kit, 23 years after his father passed away. A book of memoirs had previously been published a year before his death.

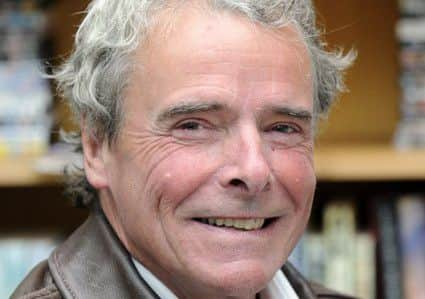

“The original edition of Christie Boy stemmed from the family’s determination that his many written memories of a Highland way of life long gone and his entertaining tales of West Coast characters should not disappear with him,” says Fraser junior, the former BBC Scotland Drivetime presenter.

“Nearly a quarter of a century later, I realised the case for publishing Christie Boy was just as strong today as it was in the 1990s.”

This was a different era, when large families were the norm and parents devoted their lives to bringing up the brood. Fraser was one of nine siblings growing up in remote Lairg in Sutherland. Another two brothers died in childbirth. “Mam” made much of the family’s clothing, while most of the food supplies were grown locally or in nearby crofts. Strict observance to the Sabbath and barefoot summers were the order of things. Fraser was just 15-years-old in Storme Ferry, Ross-shire, when he was recruited to work on the Glencoe and was soon to discover a new world of personalities aboard the firm’s fleet of steamers. These vessels were daily staples for residents of Scotland’s West Coast islands at the time and included the Plover on the Outer Islands, the Glencoe on the Portree service, the Claymore on the North Mainland and the Lochinvar on the Sound of Mull. The Pioneer was a familiar name on Islay, with the Columba servicing Ardrishaig, while the Caledonian Canal had the Gondolier and the Crinan Canal, the Linnet. Short cruises out of Oban were provided by the Mountaineer.

“Every ship had a few special characters who were out of the ordinary,” Fraser recalls.

“No matter where members of the company met, one could be sure that sooner or later the gathering was going to hear a feast of stories, some witnessed at first hand, others handed down.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAmong those were of Plover Captain Duncan “Squeaky” Robertson, so called on account of his high-pitched twang. Caught in a storm, and feared lost at sea after witnesses reported her having disappeared below the waves during a storm-ravaged trip from Harris to Loch Maddy, the ship limped unannounced into Kyle a day later. Several ventilator trumpets and ladders were missing, its funnel caked in salt and heavy damage abounded.

“We had a bit of a breeze,” Squeaky remarked to stunned port office staff on arrival.

Advertisement

Hide AdThese are the escapades of a bygone era, where notions of health and safety seemed to stretch little further than managing to stay alive. And often barely so. The unfortunate “Big Donald” had perhaps the closest escape while fishing in a boat off Kyle. The setting sun meant the approaching Lochness steamer failed to spot him and he was duly run over and his boat sunk. It was only as crew were tidying up the mooring ropes after some distance they heard his cries for help – and he was spotted in the water “hanging on grimly” to the ship’s anchor before being pulled aboard. One shudders to think what kind of payout the firm would face nowadays from an inevitable lawsuit.

A wooden fishing drifter enjoyed a similar lucky escape on a blustery night in Portree harbour when the approaching Fusilier caught a sudden violent gust which saw the steamer slice almost right through the middle of the smaller vessel stopping just short of her funnel. Rather than halting to inspect the damage, the ship’s captain Lachie Robertson instead forged ahead to his berth, with the stricken trawler wedged into the ship’s bow. It meant the fishermen were able to abandon their vessel by climbing onto the pier.

And in an age before computerised instruments and GPS, the aforementioned “Squeaky” won the admiration of dockers after he made harbour in dense fog having negotiated the “narrows” at Kylerhea. It was all down to a shepherd gathering sheep on the bank who could see the ship’s mast above the fog and kept calling out “You’re doing fine Duncan – just carry on.”

And who better to solve the mystery of Nessie than captain Peter Grant who sailed the dark waters of Loch Ness for 20 years. He never saw any monster but suggested a flight of ducks just above the surface in cloudy weather could give this illusion. The unfortunate stoker of the Plover, a chap called McDiarmid, became the butt of fun as he left the Kyle Hotel one stormy night to have his hat blown off by a mighty gust – which also captured his wig. When the landlord was later asked by new patrons if there was anything good to drink, he was able to offer the reassurance that his fare was so strong it blew a man’s wig off earlier in the evening.

The upheaval and change among the fleet and at the firm are covered, including the departure of David MacBrayne himself in 1928. His name had fronted the firm since 1878 when he gained full control and changed the name from David Hutcheson & Co which had been established in 1851. It was to last almost a century before the Caledonian MacBrayne name emerged.

The patriarch left behind a staff to whom the firm had “become a way of life,” the author laments.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“It is perfectly true that to be a member of the company earned anybody a welcome wherever they appeared in the West of Scotland.”

The transformation of the Highlands after the outbreak of the Second World War is also set out, with journeys home to Kyle requiring special authorisation as the area had become a naval base with entry heavily restricted. There are stirring tales of Fraser’s frontline experience in North Africa and the British reverses at the hands of Rommel, before the dramatic upturn with the arrival of Field Marshall Montgomery and his defiant “no retreat, no surrender.”

Advertisement

Hide AdA spell as an intelligence officer in the Italian campaign followed as the Germans were driven out of the country. Fraser ended up on Orkney for perhaps the most bizarre war victory celebrations after the Japanese surrender. A botched attempt at a victory bonfire resulted in near volcanic tar flows and much of the Kirkwall foreshore was subsequently engulfed in flames.

Fraser returned for a new post-war chapter with MacBrayne’s taking on the role of port manager in various “relief roles” around the North-West before becoming Northern area manager. But problems with industrial relations and rivalries within management eventually took their toll and after 33 years’ service, he and wife Rena, along with children Beatrice and Kit, opted for a new quieter life at the sub-Post Office of the “sleepy railway junction” of Aviemore. With the revolution in Scotland’s outdoor and skiing industry poised to descend on the town, the tranquillity was not to last.

Christie Boy – A MacBrayne’s Man is available from Amazon, £8. It will be available on Kindle shortly.