The Scotland v Chile friendly labelled the '˜match of shame'

• From Issue 6 of Nutmeg: The Scottish Football Periodical

“As a football fan I would not like for players to play on waterlogged pitches,” stated Labour MP Ian Mikardo in January of 1977. “I would also not like for them to play on blood-soaked pitches,” he added, pointedly.

However, on 15 June, 1977, that’s what the Scottish national team did, as they stepped on to the grass of Chile’s National Stadium in Santiago, a fixture labelled then and since as Scotland’s “match of shame”.

Advertisement

Hide AdTo understand why it was so controversial for Scotland to play in Santiago as part of their three-stop South American tour – which included fixtures against Argentina and Brazil in Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro, and which had the aim of acclimatising the team ahead of the following year’s World Cup in Argentina – there is a need to spool back to 11 September, 1973. That was the date of the Chilean coup d’état, in which socialist president Salvador Allende was ousted and which led to army chief Augusto Pinochet’s ascent to power.

Pinochet was a dictator. That is a fact. What is also indisputable is that he used Chile’s largest stadium as a de facto concentration camp. More than 40,000 untried Allende supporters, trade unionists and members of left-wing political parties were held there, with men kept in the bowels of the stadium and women held, and often raped, in the changing rooms of the venue’s swimming pool. “Although not much time passed when we were there, I felt that I went in as a 16-year-old girl and came out as a 70-year-old woman,” survivor Lelia Pérez later recalled in an interview with Diario UChile. “I think that all of the women who were taken into the side rooms there were subjected to sexual violence,” she added.

It was estimated that at one point as many as 7,000 were captive at the ground at the same time, with so many prisoners held in the interior rooms that there was hardly any room to lie down, leading to severe sleep deprivation. “In the search to find a spot, one fellow prisoner punched me in the stomach so that he could take that part of the floor, at which point I realised that their aim of degrading us and of turning us into animals was quickly being achieved,” explained survivor Sergio Muñoz in the documentary Estadio Nacional. Not all prisoners were subjected to this slow and painful suffering, though. Some were tortured and shot.

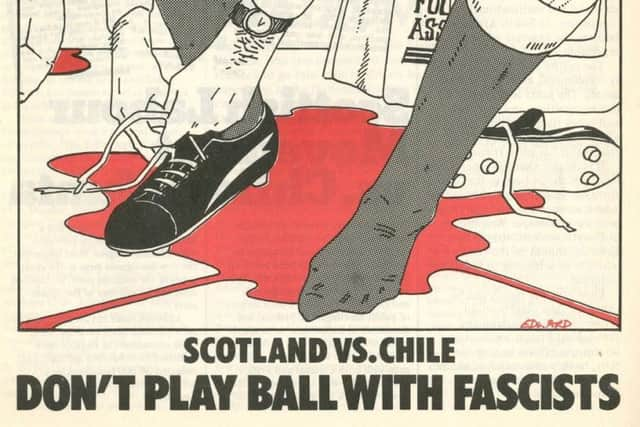

So when the SFA announced that the Scotland team would be visiting this former concentration camp for a kickabout only four years after the coup and when there were still lingering concerns over the regime’s actions, there was outcry. Some 30,000 signed a petition which was sent to the SFA and 29 different organisations expressed concern to the secretary of state for Scotland within five months of the fixture’s announcement. The Scottish Office appealed to the SFA to call it off. There were protests against the match outside Wembley when Scotland took on England. There was Scottish coverage of a press conference featuring the testimonies of some of the survivors of the camp. Three of them unsuccessfully sought a meeting at the SFA’s offices. The magazine Chile Fights dedicated its front page to the matter and depicted a Scottish player trying to tie the laces of his boots in a pool of blood, with the caption “Don’t play ball with fascists”. There were debates in the House of Commons, one so heated that a Tory MP was threatened with a “thumping” and another labelled “fascist scum” by a Labour counterpart.

As this was back in the day when a protest meant more than simply re-tweeting a hashtag, there was even a song written about the situation. “On September the 11th of 1973 scores of people perished in a vile machine-gun spree and a Santiago stadium became a place to kill, but now a Scottish football team will grace it with their skill, and there’s blood upon the grass,” was the start of the powerful piece by Adam McNaughtan, perhaps better known until then as the man behind The Jeely Piece Song. Yet the horrors described in these lyrics about Santiago were far more serious than a hypothetical breid ’n jelly bombing by the Clydeside Reds. They were also very effective, as the lyrics were printed in full by the Sunday Times after just a dozen or so performances of the song in pubs and clubs around the country.

Although some other South American teams and the Republic of Ireland had already played at Santiago’s National Stadium since its use as a detention centre, a decision which earned similar criticism in Ireland, there was precedent for refusing to play there. As part of qualification for the 1974 World Cup, the USSR were drawn with Chile in a play-off, but the Soviets refused to travel for the second leg, following a goalless draw played out in Moscow in the first match.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“The football federation of the USSR asked Fifa to hold the match in a third country seeing as how in the stadium, stained with the blood of the patriots of the people of Chile, Soviet sportsmen cannot at this time perform on moral grounds,” a statement from Chile’s opponents read. Some Fifa officials subsequently inspected the ground, which was still housing prisoners at the time yet those being held at the stadium were hidden and kept quiet and it was ruled that the match should go ahead as planned. In turn, the USSR did not show up and the South American side dribbled up the empty pitch from kick-off to score the symbolic goal, making it Chile 1, AWOL USSR 0. It was described as an embarrassment and was immediately followed by a friendly match against Santos, who had been pre-emptively invited to keep the spectators entertained in the event of a Soviet no-show.

In the end those in charge of Scottish football decided to press ahead with the match, in spite of all the various types of protest being made back home. “Having made inquiries of Her Majesty’s government and having considered the reply, the international and selection committee have decided unanimously to proceed with its plans,” Ernie Walker, the assistant secretary of the SFA, stated as he justified the game going ahead. The SFA actually had the backing of most players too, as 70 per cent of those who participated in a poll organised by the Scottish Professional Footballers’ Association stated that they thought the fixture should take place. Only 10 per cent explicitly opposed it.

Advertisement

Hide AdPart of the reason behind the players’ support, however, had to do with the implicit threat of not going to the 1978 World Cup, the reason this tour of South America had been organised in the first place. Willie Allan, the SFA secretary at the time, insisted that the game would only be stopped if the Westminster government requested it. Parliament did not demand such a suspension, which led many Scottish players to refrain from speaking out, much to the disgruntlement of Labour MP Syd Bidwell. “It would have been wonderful if one of these young men had refused to go, realising that that gesture would win him a far more important place in history than football ever will,” the politician said.

Some players simply didn’t know enough about the Chilean political climate to comment, at least not until they arrived. As goalkeeper Alan Rough explained on Real Radio many years later: “You take it that the SFA, who are taking you there, know what’s happening.” Asked if the players had been consulted on the decision to play there, Rough’s answer was a simple one. “No.” He added: “When I went into that stadium, I remember going into the dressing room and I remember seeing the bullet holes on the wall where they had lined up people and killed them. I think if we had been given more information, that there were actually people still being killed and still being arrested on the street and being taken away and shot and that it was as bad as it was when we got there, most of the players wouldn’t have gone.”

By the time they were in the dressing rooms for the first pre-match training session, it was already too late. All there was left to do was treat the match like any other game. The weather would have helped with that, as it was a misty day and local journalist Antonino Vera wrote that “it seemed like a match played at Hampden Park on a typical British night”.

It was a typical Scottish result, too, at least for that talented generation of players, with a squad that included Kenny Dalglish, Archie Gemmill and Joe Jordan. They marched to a 4-2 victory. It was 3-0 at half-time and Ally MacLeod’s Scotland side were able to survive a second-half brace by Julio Crisosto to hold out for the win, with Asa Hartford, Dalglish and Lou Macari, twice, scoring for the visitors.

A 1-1 draw in Argentina and a 2-0 loss in Brazil followed, but the tour was never going to be remembered for the results on the field, rather for the significance of the location of the first pit stop and the “tacit approval of a vicious and despotic regime” that SNP MP Donald Stewart claimed it represented. With the match having been broadcast on Canal Nacional to the entire Chilean population, the Pinochet regime could proudly proclaim that Chile was a country which foreigners were happy to visit.

That said, the trip might have had the unintended consequence of raising awareness of Chile’s volatile situation back in Scotland. “Ironically, the SFA’s determination to go ahead with the game and their contemptuous disregard for the opposition to it has probably done more than any previous issue to make British public opinion aware that all is not well in the state of Chile,” wrote Brian Wilson in the Guardian, astutely. Around 500 Chilean refugees made their way to Scotland during the dictatorship and there was increased awareness of their situation, partly as a result of the “match of shame”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAllende’s widow and human rights campaigner Hortensia Bussi even visited Scotland and ran for the post of Glasgow University rector in 1977, losing to student John Bell, but, according to the Glasgow University Guardian, “drawing attention to the conditions in Chile today”. All of a sudden, organisations such as the Chile Defence Committee and the Chile Solidarity Campaign were of interest to more than those already involved in those niche circles. The Scottish population might have become one of the most knowledgeable about the Chilean struggle.

By playing this game the Scottish national team contributed to the awareness of the Chilean situation, while the political implications would have been just as significant had they cancelled the fixture.

Advertisement

Hide AdFor many, it is considered shameful that they played at the venue so soon after the military coup and the torturing of prisoners. But, others would point out, is it really any different to have played there four years afterwards or to have played there 44 years afterwards, as all guests of the Chile national team currently do? The stadium is still in use and hosted six matches at the 2015 Copa América.

The blood upon the grass may have dried in by now, but Chile’s National Stadium remains one of the eeriest and most controversial venues in world football.

This feature appears in Issue 6 of Nutmeg, a print publication devoted entirely to every aspect of Scottish football. It is published quarterly and is available via subscription at www.nutmegmagazine.co.uk