Robert Glancy: '˜I thought it was normal to have a crocodile in the school pond'

My parents have been called lots of names. Names that always framed them as outsiders. In Africa they were mazungus – white folks. They became infidels in Brunei, and the Chinese re-christened them Gweilo – foreign devils.

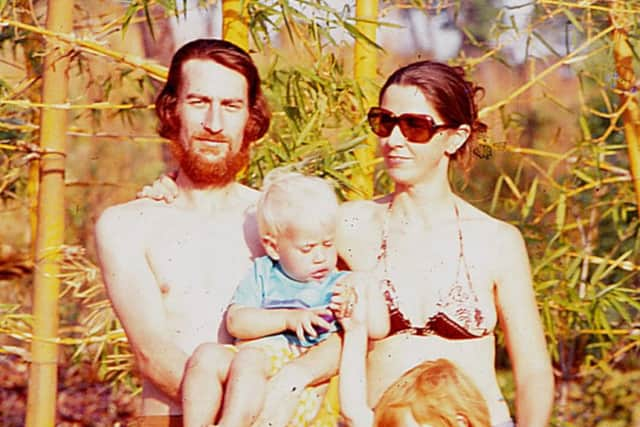

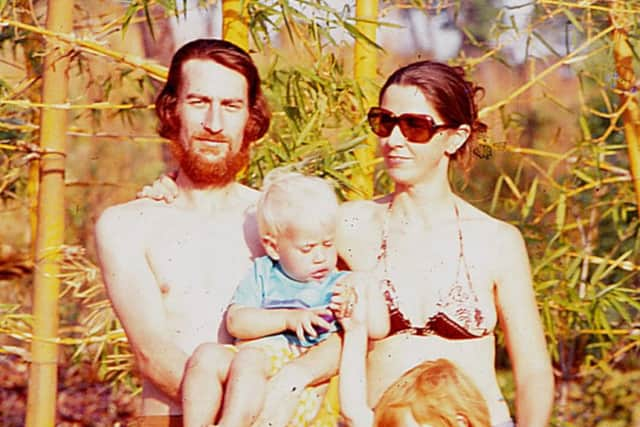

Children get only a cloudy version of their parents’ history. But one thing is clear. My parents had a metamorphosis. In the Seventies they went to Africa and bloomed from pale Celts into sunburnt hippies. A transformation underscored by the fact that all their Celtic photos are in dour black and white but their African ones are in rainbow colour.

Advertisement

Hide AdFlicking through the photos it seems the world itself, not just my parents, changed forever. Maybe it did. Here’s what they show. Irish-Mum is a nurse in grey clothes - but Zambian-Mum is slim in a bikini, wearing Jackie-O shades. She has about her a touch of glamour that my sisters and I will soon rub out of her. Scottish-Dad is stiff in a suit – but Zambian-Dad squints into the sun, face scribbled with a beard, hair long and wild. Utterly transformed, he’s become – Jesus. Ironic, as my parents left home to escape Catholicism – they were running from Jesus.

It doesn’t take much imagination to get on a plane these days. But back then it must have taken some nerve to make the leap from strict Catholic society to the Zambian bush.

Mum was a midwife. Dad taught Zambians and Mozambique refugees who’d fled the civil war desperate to be educated and keep their heads above Africa’s ever-rising poverty line.

I was born in Zambia and moved to Malawi when I was four. And though we were part of the community, we were still expatriates – mazungus – still outsiders. I remember mum often saying, ‘We need to go back to Britain – we need to go home!’ This always confused me. Returning home was a tough concept for me. How could I return to a home I’d never lived in?

My parents were a couple of crazy mazungus out to save the world. And though Africa, and the other places they lived, branded them with exotic nicknames, in their heart of hearts they are always Celts. But for me, a white boy born in Africa my roots were always more tangled and muddy.

Leaving Malawi at 14, on the cusp of adolescence, wove Africa and my childhood tightly together. At the time I didn’t think anything was odd. You accept your childhood as normal. I thought it was normal to have a crocodile languishing in the school pond, its greasy eyes reflecting the sumptuous children strolling past. I assumed all countries had portraits of their leaders in every bar, office and restaurant. Normal for a national newspaper to constantly praise our glorious president, who’d freed Malawi from the evil British. The newspaper famous for two things: toeing the party line and making fabulous mistakes. The best of which was a misspelling that was corrected the next day: ‘We apologise for misspelling Clit Eastwood. It is, of course, Cxxx Eastwood.’ All as normal as a cup of tea.

Advertisement

Hide AdThere was no free press in Malawi. The only uncensored news was the BBC World Service; a posh dismembered voice that travelled thousands of miles from a strange island called the United Kingdom. My older sister was more influenced by the UK than by Africa.

I went to a Malawian school, but Jo attended a Scottish boarding school, and it was there that Jo became sophisticated. For Jo sophistication meant ordering prawn cocktails at restaurants.

Advertisement

Hide AdJo also brought Britain to Africa in a very distinctive way – her haircuts. Returning to Malawi each holiday, Jo’s hair was a snapshot of the UK. One holiday she stepped out of the plane with giant Joan Collins curls. Next holiday Jo arrived as a ginger Princess Diana. When Jo admitted how much her hair cut cost, mum yelped, ‘Fifty what? Pounds! A local family could live a year on that!’ Jo just shrugged and ordered a prawn cocktail; far too sophisticated to worry about such things.

Jo didn’t just bring Britain to Africa – she also brought Africa to Africa, in the form of Live Aid. There was no TV in Malawi. So when Jo first went away to boarding school my parents decided to buy a VHS-player. A replacement of sorts – you lose a sister but gain a VHS. I was pretty happy with the arrangement.

The year Jo brought back Live Aid on VHS I watched pop stars with epic hair explain what Africa was really like. But Live-Aid- Africa was nothing like my Africa. Live-Aid-Africa was full of sick children with balloon bellies. This wasn’t the Africa I lived in, yet it was the Africa that lived in most people’s minds. There was, of course, poverty and disease in Malawi. If Malawian fashion was stuck in the flared-70s then Malawian diseases were decidedly medieval: leprosy, tapeworm, elephantiasis. With one contemporary addition spreading as mum began delivering HIV-babies.

Generally though, Malawi was a high-functioning nation. Which made my new VHS a warped looking glass forcing me to see that ‘normal’ was a relative term. It showed a VHS-Africa populated by Meryl Streep and syphilitic men in safari suits.

And when I left Africa I found my memory overpowered by films and clichés.

Having been away since I was 14, I returned in 1994, aged 19, to backpack through my childhood and to see what was real and what was manufactured by my receding memory.

Advertisement

Hide AdThey say you can’t go home. They’re right. I returned to a very different Malawi.

I was different too. It wasn’t until I was far away from Malawi that I saw it clearly. As I grew up my parents told me about the real Malawi, a place that jarred against the idyll of my childhood, a place where people who said the wrong thing were ‘vanished’, a place where our glorious president turned out to be a brutal dictator.

Advertisement

Hide AdBy 1994 the dictator, His Excellency the Life President Dr H Kamuzu Banda, had fallen short of his epic title, not keeping the job for life, having been toppled while still breathing – but only just. It had been a long reign. Banda took over when the British left in 1961; his arrival heralded by great hope and goodwill, which he immediately squandered.

Yet still Malawi, The Warm Heart of Africa, was held up as a postcolonial success story as Banda sustained stability for many decades – but at a price. And that price was being a tyrant who quashed opposition and freedom of speech. But by 1994 there was a new government, and people were finally allowed to talk about the ultimate taboo – politics. However, though the freedom to speak was good the content of that speech was not. The path to democracy was littered with cronyism and corruption, the new government was little better than Banda, and, as early as 1994, some had already begun to talk of the Glory Days of Banda.

When I returned in 2015 the revision of history was complete. There was even a monument to Banda, an inappropriately expensive one that I’m sure he’d have loved. And corruption had reached farcical levels with BenzAid – aid money squandered on Mercedes – followed by CashGate – a dire corruption scandal. And all this in a country where most survived on 50p a day.

On a more personal level, it was hard to recognise this place called Malawi. Mum visited her old place of work, Queen Elizabeth II Hospital, and came back in tears. The state of the hospital was terrible; things had regressed. When we left in 1989 there were four million people – by 2015 it was 16 million. Malawi was looking more like Live-Aid Africa than ever, a weary nation struggling under the weight of its own population.

Many times on that trip we passed the university dad had taught at, each time he refused to go in, fobbing it off, trying to be casual, when in fact, I sensed he didn’t want to risk it, to see what mum saw at the hospital, to face the fact they’d failed to save the world.

Maybe this wasn’t their world to save. Magic remains in Malawi, in the generosity of its people and in the majesty of its lake, but The Warm Heart beats a little cooler than before.

• Please Do Not Disturb by Robert Glancy is published by Bloomsbury, hardback £16.99, ebook: £14.99