Renaissance man Rory McEwen’s work in new exhibitions

A TV music show with an eclectic mix of performers hosted by a genial presenter who is also a musician himself – no, we’re not talking Later… with Jools Holland but an earlier incarnation of the format. Hullabaloo was presented by the charismatic Scot Rory McEwen and between 1962 and 1964 showcased the post-war folk revival, birth of skiffle and the rhythm and blues that fuelled British rock and roll. Not only did McEwen compere, he also performed, playing his 12-string guitar and inspiring the likes of Van Morrison and The Animals. However, few tapes of the show survived.

When one finally surfaced and found its way to McEwen’s daughter Christabel, who had never seen the show, she was delighted and stunned. “I sat down and watched it with my husband and at the end of it he turned to me and said, ‘You married your father.’”

Advertisement

Hide AdHer husband is Jools Holland. “They are both musicians and it’s not just about presenting, it’s about playing too. Sharing. There’s no other programme like Later …”

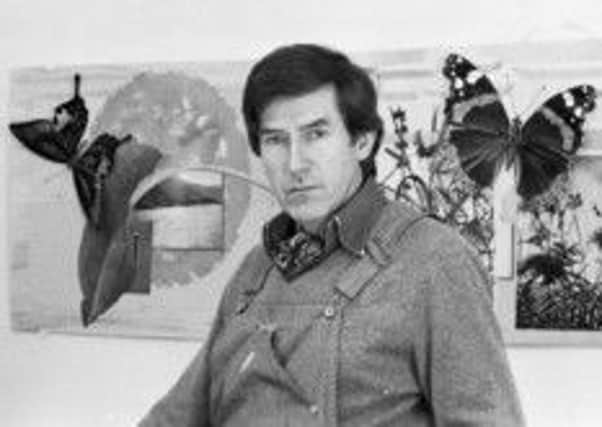

Back in the 1960s there was no other programme like Hullabaloo but that wasn’t the only string to McEwen’s guitar. Before his untimely death in 1982 at the age of 50, he was also a hugely influential artist whose work is held in private collections worldwide, and on display in the British Museum, V&A, Tate, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art and Moma, New York.

It was McEwen’s botanical paintings that made the biggest impact in the art world and these are now being showcased at a major summer exhibition at Kew Gardens, while in Edinburgh the Royal Botanic Garden is also celebrating him with The Tweed Road, an exhibition of his rarely exhibited glass sculptures, and documentary photographs of a ‘sculptural environment’ he made for the Richard Demarco Gallery, where he also exhibited throughout the 1960s. It was Demarco who fostered his links with the German artist Joseph Beuys, and saw them collaborate on a project, or “action”, that has ‘Edinburgh Festival’ and the 1970s written all over it, and which is also being shown in the exhibition in the capital.

The film was taken on a dreich day in the summer of 1970 when a convoy of cars left Edinburgh containing Beuys, McEwen and Demarco, taking The Road to the Isles, headed for the Celtic land of Tír na nÓg, the ‘Land of Forever Young’, where at midsummer the sun sets and rises within a brief moment. Beuys called a halt at the edge of Rannoch Moor, emerged from his car and shaped a “large slab of gleaming and quivering semi-transparent gelatine and proceeded to sculpt it into the organic shape he thought fit to hold symbolically above the moor’s surface”, recalls Demarco. All the while, McEwen filmed it on his cine-camera and the result was performed twice a day for a week at that year’s festival.

“I remember complaining about the heavy rain and poor visibility,” says Demarco, but Beuys replied, “All weather is good weather.”

McEwen, a keen fisherman and stalker, was in complete agreement. “They were true countrymen,” he says, “both delighting in the Scotland of farmers, crofters, botanists and fly-fishermen.”

Advertisement

Hide AdThe book that accompanies the Kew exhibition, both titled Rory McEwen The Colours of Reality, shows both sides of the talented musician and artist and in it friends and colleagues, including editor Martyn Rix, share memories of this Eton and Cambridge- educated artist and musician who championed and befriended the musicians of the beatnik generation and also blazed a trail in the art world.

A cultural all-rounder, his work was a synthesis of the experiences and influences that shaped him, from the Border ballads and Scottish songs of his carefree country childhood, to the blues music and the post-war folk music revival to the graffiti and pop art of his friends Cy Twombly and Jim Dine.

Advertisement

Hide AdCharming, handsome, and with a talent for making contact with people – his friend the former Conservative Party politician and later chairman of Sotheby’s and of the Arts Council of England, Grey Gowrie, says he was “intelligent, funny and good looking to an unfair degree” – McEwen was ahead of his time. Born into the Scottish aristocracy in 1932, he spent his early years at Marchmont, a winged Palladian mansion in Berwickshire, the son of Conservative MP Sir John McEwen, and Bridget, the granddaughter of botanist and illustrator John Lindley.

Music, nature and art were in his blood and his artistic talents were evident early on as the young Rory and his six siblings wandered the family estate with their French governess Madamoiselle Philippe, drawing the flowers and grasses they saw. His love of jazz was sparked then too, thanks to elder brother Jamie, and continued through his years at Eton and national service, and on to Cambridge, where he wrote and performed with the Footlights and hung out with Peter Cook and Dudley Moore.

Karl Miller, later editor of the Spectator, where McEwen became art critic, was also a friend. “He was a bit of a liability from a left-wing point of view,” remembers Miller, describing how someone reported seeing McEwen on a station platform, “a terrible man … dressed in an Inverness cape, a Scots bonnet and carrying a pheasant over his shoulder and a guitar with ribbons”. “I didn’t tell him it was a friend of mine.”

After Cambridge, McEwen and his brother Alex set sail for the US in 1956, on a personal pilgrimage in search of their blues heroes, visiting the widow of folk and blues musician Leadbelly, who was a legend on the 12-string guitar. Such was their charm that she let Rory play her late husband’s guitar, inspiring him to find one of his own in a pawnshop. The brothers then gigged their way across America, recording Scottish Songs and Ballads and becoming one of the first British acts to appear on the Ed Sullivan TV show that launched The Beatles.

Back in Britain, McEwen’s fame rose as he began hosting the top-of-the-ratings, late-night folk and blues programme Hullabaloo, featuring the likes of Long John Baldry and Sonny Boy Williamson, and watched by the young Billy Connolly and Van Morrison. Morrison says, “He was actually the only person I’ve heard that played 12 string the same as Leadbelly … he was the only one that could actually do it for real.”

McEwen was also a regular on the daily BBC Tonight news programme, writing and performing topical calypsos, while working as art editor for the Spectator. Work and home life flowed seamlessly into one another and the house he and his new wife Romana bought in London was a hub for gatherings of the hottest creative talents and some of the biggest names in entertainment of the day.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn the airy drawing room, Barbra Streisand could be seen chatting to Jonathan Millar, or the Everly Brothers jamming with John Lennon. It was there that George Harrison learned sitar from Ravi Shankar, who lived in a house at the bottom of their garden and handed out hash cookies at parties as well as playing private concerts in their basement. The influence McEwen had in bringing artists together is epitomised by his throwing a party for Bob Dylan in 1963, then taking him to meet the poet Robert Graves.

Folk singer Martin Carthy says, “You saw the world when you went to Tregunter Road [the McEwens’ Chelsea home]. Bob Dylan, George Melly, Princess Margaret, The Beatles …”

Advertisement

Hide AdNot that the young Christabel, now 50, knew who the beautiful people – with their glamorous beehives or virtuoso guitar playing – attending her parents’ house parties, were.

“We were always welcome at the parties but we were very small. It was only as I grew up I realised some of the people there were very interesting,” she says. “It was a very artistic upbringing, surrounded by art and artists. My father would also play his guitar, although I never saw him play publicly,” she remembers.

“He would let us into his studio and his art was never at the expense of his family. He was always the centre of fun and entertainment, very energetic and full of curiosity about everyone. Everyone would say, ‘Who is this marvellous man and when can we meet him again?’

“He was a wonderful parent, very affectionate and always lit up his part of the world. It seems astonishing that at the same time he painted so many extraordinary paintings – 400 over his lifetime, working 12-hour days sometimes – and also had the time to write poetry and letters and maintain deep friendships with people, and travel all over the world. All before he was 50.

“When he had cancer and a brain tumour, it stopped him for a bit and then he went into remission and worked even more intensely for a while. The more I learn about him, the more amazed I become,” she says.

Back in Edinburgh in the early 1960s, McEwen and his brother hosted their own live shows to sell-out audiences at three successive Edinburgh Festivals but with a young family to support, and his botanical drawing being his bread and butter, McEwen decided to immerse himself in his art from 1964 onwards. “He realised if he was going to be a serious artist, he had to focus on that,” says Holland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAs well as the exquisitely detailed watercolours of plants on vellum – which he termed his “plant portraits” and which inspired a whole generation of botanical artists – he also worked in colour-refracting Perspex sculpture and created large abstract works in glass and steel.

However, it was the ferns, flowers and grasses of his youth to which he returned and at which he really excelled. According to botanist and author Martyn Rix, “He really brought it from illustration into an art form in itself by going into such intense details so it was beyond photography. He did modern abstract work as well, always going off and trying new experimental things, but the botanical paintings are his main contribution to art. He continued a tradition and created something new, bringing a modern aspect to a classical tradition. He’s still better than anyone else.”

Advertisement

Hide AdSumming up McEwen’s contribution to art, Gowrie says, “I hesitate to define Rory as a Scottish artist. By his very nature, he belonged to the international art world.”

The international art world doesn’t seem to want to let him go either, with collectors hanging on to his paintings so that they rarely come on to the market. “It’s hard to get hold of them because people hold on to them,” says Holland. “I’ve got one of his tulip prints and one of his big tulip paintings.

“I think they’re just fantastically beautiful and have a very particular quality that transcends the subject matter. He seems to have painted something more than just the flowers. He was really searching for the essence of things. He was a seeker of truths.”

Now the age at which her father died, Holland found that helping with the exhibition has given her a new perspective on someone she never knew as an adult. “I was only 20 when he died so I hadn’t developed an adult way of thinking. He got ill when I was 17, with cancer then a brain tumour. I never knew him as an adult. I miss the conversations we haven’t had the opportunity to have. This feels like that eastern idea of honouring your ancestor. Tracking down his paintings, it’s been absolutely overwhelming how much people loved him and it’s the right time with his contemporaries hitting their 80s,” she says.

“Van Morrison said he has been written out of musical history and it was getting close to the same thing in art history, so it’s been a chance to reinstate him. He was so pivotal in so many lives in the music and art worlds and I’m just glad he is being remembered and that this exhibition will give a whole new generation of artists the opportunity to see what he did.”

Then in the spirit of her father, she adds, “And what they can do.”

Advertisement

Hide Ad• Rory McEwen The Colours of Reality is at The Shirley Sherwood Gallery of Botanical Art, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, until 22 September;

• Rory McEwen The Colours of Reality, edited by Martyn Rix, is published by Kew Publishing, £32/£25 paperback;

• Rory McEwen (1932-1982): The Tweed Road is at Inverleith House, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, until 23 June

Twitter: @JanetChristie2