NMS show set to shatter some myths about glass

Artists in Britain are at the forefront of a movement to challenge this perception, embracing glass in innovative ways and pushing the boundaries of techniques.

A new exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland will examine the diverse work of 15 established and emerging glass artists in Britain today. Opening on Friday, Art of Glass – which is presented in partnership with The National Centre for Craft & Design – features groundbreaking works utilising everything from neon to stained glass.

Advertisement

Hide AdSince the Studio Glass Movement of the 1960s, Britain has had a significant impact on how glass is perceived as an art form. Both national and international glass artists have increasingly based themselves here, drawn to the teaching and world-renowned facilities on offer. They are working with glass in a variety of ways, whether manipulating it in a hot glass studio, casting it in a kiln or using new technologies such as waterjet cutting and 3D printing.

The artists featured in Art of Glass are based around the UK, working from both isolated rural studios and busy urban locations. Among them are four Scotland-based artists, whose works are pushing the medium of glass to its physical and artistic limits.

Geoffrey Mann

The glass programme director at the Edinburgh College of Art, Geoffrey Mann was one of the first glass artists in the UK to introduce digital technology into his practice. For Art of Glass, he has created The Leith Pattern, which explores the myth that the archetypal wine bottle originated in Leith.

“This was something I thought I’d heard, a sort of an urban myth,” says Mann. He worked with a historian to research the story, before interviewing Leithers themselves on the subject. Soundwaves from those recorded interviews were used to create a “living” bottle that resonates with human stories.

“I was interested in how the people of an area make a place, not things like factories or shops,” he says. “I wanted to look at how I could take a person’s story and embody that within the object. I use digital tools as a way to see things that are above and beyond our own reality. I can’t see or touch motion or soundwaves, but I can create physical artefacts which represent them.”

There are many steps on the journey to creating the finished piece, including animation, 3D printing and kiln casting. The end result is a moment frozen in time; rippling sound waves and a rigid, traditional bottle mashed together. “The object has potential energy built into its form,” says Mann. “It looks like it’s actually trying to move.”

Karlyn Sutherland

Advertisement

Hide AdWhile undertaking a PhD in Architecture, Karlyn Sutherland’s research into the emotional power of place led her back home to Caithness.

Based in Lybster, she is influenced by the quality of light in the area. Much of her recent work reflects on childhood memories, and she’s created a piece which draws on a memory of looking in a mirror in the house she grew up in at the reflection of the harbour, seeing everything in reverse and imagining what it might be like to live in that other world.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Glass allows me to explore architectural atmosphere, space and light in a way that no other material can,” she says. “I reference perspective drawing in my work to create that sense of illusion and to play on a notion of detachment from and attachment to place, since perspective gives a false impression.”

Pinkie Maclure

Perthshire-based Pinkie Maclure began working with glass almost by accident. Her partner was working as a self-employed stained glass window maker, mainly restoring Victorian windows, and making new ones for front doors. He asked if she could help him out.

“I suppose I didn’t choose glass; glass chose me,” she says. “As I found out more about it, I became more and more frustrated with the prevailing attitudes towards stained glass. There seemed to be this view that it was a dying art, that modern stained glass has to be bland, meaningless and abstract.”

She began researching medieval stained glass, looking at examples in York Minster and in Northern Europe. “It was bizarre, funny and bewitching,” she says. “I was fascinated by it and wondered why no one was doing anything like that today.”

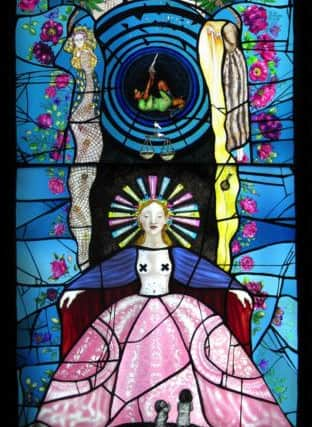

For Art of Glass, she has created Beauty Tricks, which critiques the human and environmental impact of the beauty industry and the pressure women sometimes place on themselves and their daughters.

At its centre is a representation of a feminine beauty ideal; at her feet is scattered plastic packaging; a side of the beauty industry which contributes towards an ugliness in our natural environment. Just like medieval stained glass, closer inspection reveals quirky details; references to Botox, plastic surgery and liposuction.

Harry Morgan

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I was introduced to glass processes in high school,” says Harry Morgan, an emerging artist and designer based in Edinburgh. “I found that I particularly enjoyed the anticipation of opening the kiln. Melting things appealed to me more than painting.”

Morgan’s work is known for its unusual use of materials and experimental approach to traditional processes. Referencing both ancient Venetian glassblowing and Brutalist architecture, he has created two pieces for the exhibition – Dichotomy I and II – which juxtapose brittle glass and weighty concrete.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I’m really drawn to the fragility of glass,” he says. “As children, we’re told to be careful with glass. We’re told that it’s dangerous, so we grow up with a sense that it’s precarious, that we should be cautious around it. I like to play with this tension in my work.”

The two pieces he has created for Art of Glass are his largest to date. “I saw a demo of an old Venetian technique called murrine, where glass threads are pulled by hand from a furnace in different colours. They are then put into a mould and fused together to create a pattern or motif. When the glass is cut you have tiles with a pattern.”

Mesmerised by the glass in its thread form, he paired it with concrete, highlighting the contrast between the two materials, while binding them together as a single object.

Part of the Edinburgh Art Festival, Art of Glass is at the National Museum of Scotland from 6 April-16 November, free, www.nms.ac.uk/glass