Maripol still in fashion after more than 20 years

Earlier this year, Dundee Contemporary Art curator Graham Domke boarded a flight back from New York with a very special suitcase. His cargo was a selection of clothing, jewellery and photographs by the legendary stylist Maripol.

“It was the safest and easiest way of doing things,” he says. “It never left my sight. There was a frisson of excitement for me in having more stylish things than usual in my suitcase.”

Advertisement

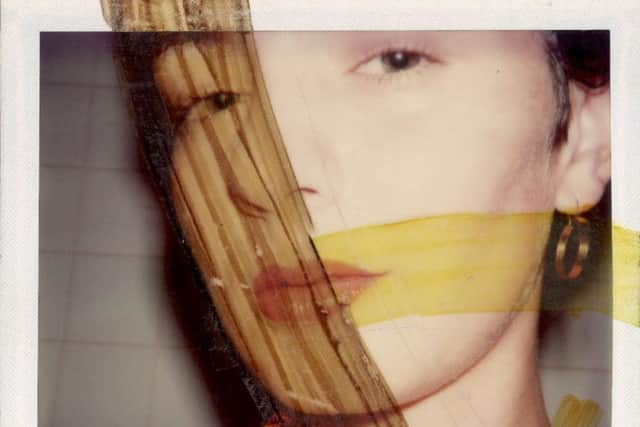

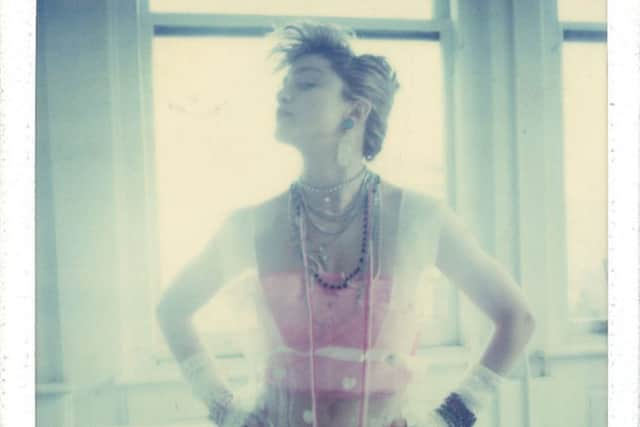

Hide AdDomke has achieved something of a coup in bringing Maripol’s work to DCA, to be shown in Scotland for the first time. Born in France, but resident in New York since the 1970s, she is variously a stylist, photographer, filmmaker and jewellery designer, and was behind Madonna’s Like A Virgin look, inspiring a decade of bracelets and crucifixes. Her iconic Polaroid photographs captured the spirit of 1980s New York.

Boldly, Domke is showing her work along with that of two Glasgow-based contemporary artists, Clare Stephenson and Zoe Williams, in a show which brings together art, film, photography and fashion.

“We’ve called it Spring/Summer 15, which is a calling card to say that you’re going to come in and it’s going to be an explosion of colour and glamour,” he says. “To me, it’s an exhibition about the multi-hyphenated descriptions required to describe artistic creativity. In real terms, these are just creative artists.”

For him, meeting Maripol and working with her to select work for the show was a chance to work with one of his heroes, a “dream come true”.

“She was so generous with her time, and she was interested in this project because it’s not just someone coming, saying, ‘I only want to show the photographs’, or ‘I want you to design something’. This exhibition quite holistically wants to look at her body of work, but also place it in the context of work being made by younger artists now, to say she is a touchstone for that kind of work.

“She is just as vital and culturally involved as she ever was, she’s working on a new film, she’s making music, she’s putting out amazing collections. In some ways, she is not as recognised as she should be in the art world, but I think that’s changing. The show really does justice to the Maripol archive and shows how relevant it is to contemporary practice.”

Advertisement

Hide AdSpeaking on the phone while on a visit to Paris, Maripol says: “The thing that bothers me is when people stick me in the past, when actually I do new work all the time.” And she does – recent work includes a documentary on artist Keith Haring, a collection of jewellery for Marc by Marc Jacobs, and a capsule collection of clothing for über cool young French fashion house Each X Other. She is in demand as a photographer, shooting in Polaroid for fashion magazines.

“I just did a shoot with seven models, that is extremely difficult with Polaroids. I’m always doing portraits of people. My photographs and art go on. It’s only the time that I’m rushing after, when we get older we run out of time for some reason – or time goes faster.”

Advertisement

Hide AdMaripol moved to New York in 1976 as an art graduate and settled in downtown Manhattan, a city then on its uppers, but vibrant with underground artistic life. She and her boyfriend, photographer Edo Bertoglio, hung out at The Garage, Andy Warhol’s Studio 54 and Max’s Kansas City with actors and performance artists and musicians. Maripol got her first Polaroid camera in 1977 and began to photograph their friends: Warhol, Madonna, Jean-Michel Basquiat, film director Vincent Gallo, singer Klaus Nomi.

Maripol’s Polaroids are now in demand by galleries, and her work considered influential, especially by younger artists. She says she was experimenting, just as artists do now, exploring the technology of the time – the Polaroid camera, the Xerox machine – scribbling on her Polaroid images with marker pen and nail varnish, or turning the camera around to take instant self-portraits.

“It is what you do with an iPhone now, it was instant. I was able to use it, going out, taking pictures of faces. If I was making clothes or jewellery, I could take pictures of those, exactly like Instagram. I refused for two or three years to be on Instagram. My son finally said: ‘You need to do this, you’re a photographer’”. Did she think she was making art? “No, I never took pictures in a calculated way, if I did I would be better off! It’s a witness of the time.”

Domke says the Polaroids deserve to be regarded as artworks. “They are instant, but they are also incredibly well composed. I see clichés in a lot of photography, but somehow she manages to transcend that. It’s also the access, the candour in the photographs – the ones of Madonna are incredibly intimate, she is not putting on a show for these photographs, she is with a friend.”

Maripol says she became a stylist almost by accident. People just looked at her – a petite, chic figure with cropped hair and a passing resemblance to Coco Channel – and assumed that’s what she did. “I didn’t dress well, actually, I dressed differently, with some panache. I remember someone once asked me, ‘How long does it take you to get dressed in the morning?’ and I said, ‘As long as it takes you’. They would call me ‘Coco’ which was so flattering, she was my hero.”

She met Madonna on a night out at the Roxy, and when Madonna was unhappy with the clothes her record label wanted her to wear for her Like A Virgin photoshoot, it was Maripol to whom she turned.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe shabby-romantic style created that day became iconic, and was revived in 2010 by Marc for Marc Jacobs with a jewellery collection by Maripol. She went on to work with Grace Jones, the first to wear her trademark rubber bracelets, and to style Debbie Harry for Parallel Lines. She was the driving force behind the cult film, Downtown 81, made in 1981 with the young John-Michel Basquiat, but not released until 2000.

The DCA exhibition will celebrate Maripol’s style, then and now, with clothing and jewellery, as well as photographs, and juxtapose Maripol’s images with Clare Stephenson’s sculptural installations and Zoe Williams’ films.

Advertisement

Hide AdWilliams, who graduated from Glasgow School of Art’s MFA course in 2012, says she’s delighted to be showing with Maripol. Her film Drench, made for her MFA show, echoes the 1980s sensibility, and her new film made for the DCA show, Fleece, also addresses themes which strike a chord with Maripol’s work.

“Maripol’s style is very distinctive, so in a way you can’t do something relating to that too directly,” says Williams. “But Fleece is very much about adornment, jewellery, materials, textures and how they might be used in relation to the body.”

Domke adds: “It fitted like a glove to put these artists in together. The sensuality and the glamour aspect is there, that peacock-strut of a catwalk runs through the exhibition. I think all the work has teeth, and charisma and personality. People are in for a treat.”

Maripol, Zoe Williams and Clare Stephenson: Spring/Summer 15, Dundee Contemporary Arts, today until 21 June

FOLLOW US

SCOTSMAN TABLET AND MOBILE APPS