Letters sent to legendary Scots doctor go online

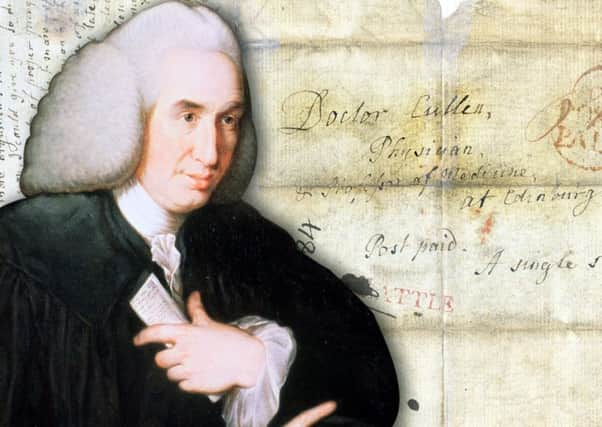

Physician, chemist and agriculturalist William Cullen, who died in 1790, was one of the most important professors at the Edinburgh Medical School.

A central figure in the Scottish Enlightenment, Cullen was physician to the philosopher David Hume, a friend of Adam Smith, president of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh and King’s Physician in Scotland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAs the most influential medical lecturer of his generation, he drew thousands of students to the Medical School and people wrote to him for advice and treatments. He generally charged two guineas a time, with fees waived for poorer patients and presbyterian ministers.

Cullen meticulously filed all his letters and responses. The archive of what he called his “epistolary practice” consists of 17 boxes of loose letters and 21 bound volumes of his replies, more than 5,000 items in all.

The collection is one of the greatest treasures of the Sibbald Library of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. Until now, it could only be accessed by visiting the Sibbald Library.

Now, more than 300 years after Cullen’s birth in 1710, and thanks to four years’ work by researchers at Glasgow University, doctors, students and anyone wanting to learn more about the history of medicine and the 18th century can access a dedicated, interactive collection.

The correspondence spans the mid-1750s to 1790. Initially, Cullen kept copies of his replies in the form of written transcripts then after 1781 he duplicated them by means of a “wet-paper”, or “pressure”, copying machine newly invented by his fellow Scot James Watt.

Examples include a letter from James Boswell asking for advice about the care of his friend, the dying Dr Johnson; inquiries about a Russian princess with gout; and how to provide relief to a patient who became ill after consuming too many cucumbers.

Advertisement

Hide AdFrom Charleston, South Carolina, there is a letter from a Scottish plantation owner asking how to cure a slave’s epilepsy.

Recommended treatments included cold bathing, purging, vomiting, blood-letting, “flesh brushing” and the application of leeches, all for conditions ranging from fevers and colics to “horrors”, scabs, teethings and delirium.

Advertisement

Hide AdPractical advice often reflects Cullen’s preoccupation about the impact on health of climatic or environmental factors, such as dryness and dampness, heat and cold.

The letters also reveal he is deeply concerned with the importance of “habit and custom”, in which he included diet, exercise and the exposure to social pressures – what might now be loosely termed “lifestyle”.

Dr David Shuttleton, reader in literature and medical culture at Glasgow University, said: “This will offer considerable new insights, not only into the history of medical practice, but also into wider society at that time.”* l http://cullenproject.ac.uk