JD Fergusson: Colourist with a modern touch

The painter, JD Fergusson, was the only British artist who was a partner and not merely a spectator in the dramatic events in Paris that transformed modern art at the beginning of the last century. This sets him apart from the other three Colourists with whom his name is always associated. So far as they were a group, he was happy to be part of it. He was also a close friend of Peploe from early on and the two often worked side by side and influenced each other in a variety of ways.

Nevertheless, Fergusson’s ambition was more focused than the others. He had a vision of modernism and indeed of a modern Scotland which was quite his own. It sets him apart, so it is appropriate that following the exhibitions of Peploe and Cadell at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (SNGMA), and of Leslie Hunter at Edinburgh City Art Centre, Fergusson should come last and provide the finale. (The National Gallery’s three exhibitions have all been admirably curated by Alice Strang.)

Advertisement

Hide AdPerhaps in belated recognition of his importance, Fergusson has recently had more attention than the others elsewhere too. He was the subject of a major exhibition at the Hunterian a couple of years ago and now concurrently with the exhibition at the SNGMA, there are Fergusson exhibitions at the Scottish Gallery, Bourne Fine Art and Alexander Meddowes in Edinburgh. Ewan Mundy is showing his work in Glasgow, while in London there have recently been shows at the Portland Gallery and the Fine Art Society. Finally the National Gallery exhibition is in partnership with the Fergusson Gallery in Perth, the gallery that was set up to fulfil his wishes and those of his partner Margaret Morris, and where a complementary exhibition is also showing.

There are more than 100 works in the National Gallery show, 75 in the Scottish Gallery and no fewer than 150 drawings at Alexander Meddowes. Ewan Mundy and Bourne Art both have smaller shows. Nevertheless, the effect of all this is to give a real sense of the scale of Fergusson’s achievement and also of his extraordinary energy. It is also ironic, however, given all this attention, that in his lifetime, like so many truly avant garde artists, he enjoyed some recognition but very little success, selling only occasionally and never making enough to live off his art.

Fergusson was born in Edinburgh and grew up there at a time when, thanks to painters like William McTaggart and Arthur Melville and thinkers like Patrick Geddes, the idea that Scotland and Scottish art could take their place in the modern world as of right was not questioned. With this confidence behind him Fergusson went to Paris. At first he visited each summer, but then in 1907 he settled there and his excitement is palpable in his work. At Alexander Meddowes, in successive pages from his sketchbooks hung side by side on the walls, you can see his responses day by day, hour by hour, even. He drew people, women especially. He loved their hats and brought out, as nobody else did, the qualities that made elaborate Edwardian headgear dramatic and even sexy. Manet also inspired some wonderful fluid still lives, but Fergusson quickly moved on to be more adventurous as he drew and painted the cosmopolitan world that he was part of. La Terrasse Café d’Harcourt is a brilliant reflection of it. A woman in a glamorous pink dress and spectacular hat stands in the middle of a restaurant. Peploe, who came to join Fergusson in Paris, is sitting at a table in the foreground.

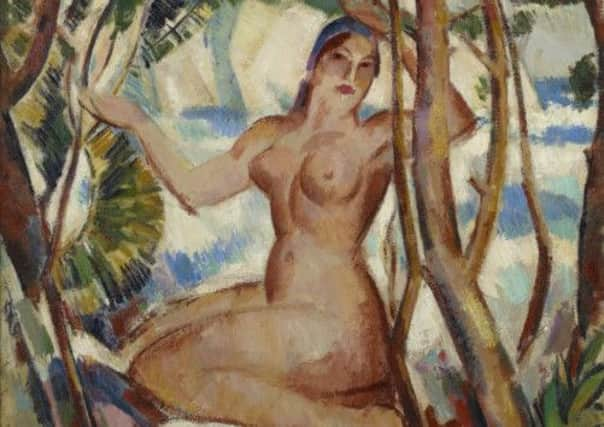

In Paris, Fergusson exhibited alongside Matisse and the Fauves. He knew Picasso and understood Cubism, but he was his own man. La Force of 1910, aptly named, is a spectacular female nude that would hold its own alongside any contemporary expressionist painting. It is not beholden to anyone, however, but reflects the artist’s own vision of the power of the feminine. This is a constant theme in his work and in his life too. In his painting, it looks back to Gauguin, but is also paralleled by DH Lawrence among his contemporaries. A drawing of Frank Harris at the Scottish Gallery dated 1905 also reflects this interest, for it demonstrates Fergusson’s early friendship with Harris, author of My Life and Loves, the scandalous erotic autobiography that anticipated the writing of Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin.

The Pink Dress at Bourne Fine Art, also from 1910, is as sensual as La Force, but the background is constructed from fragmented intersecting planes. This is seen even more strikingly in From My Studio Window, a nude woman standing against an open window and a wonderful image of the interconnectedness of things. The influence of Cubism is present here, but Fergusson also discovered for himself the philosophy of Henri Bergson, whose vision of the dynamic interconnectedness of our experience of space and time was an important part of the inspiration of the Cubists. However, Fergusson added his own dynamic of the erotic to Bergson’s (and the Cubists’) more chaste account of the rhythm of human life.

It is that dynamic, erotic rhythm that he celebrated in his astonishing painting Les Eus. A composition of six, life-size naked figures dancing in a primeval forest, its scale alone displays the artist’s ambition. He did not exhibit in Scotland till 1923. Perhaps with reason. He knew this mix of sex and modernism would be altogether too strong for the Scottish public.

Advertisement

Hide AdHis idea of rhythm informs all his art and is especially striking in his drawings. His style is firm and bold, but he composes as he draws, improvising with the fluency of a jazz master. At Alexander Meddowes a small square drawing of a still life is packed with such energy that the same idea translates with complete assurance onto a big scale in the still life La Bête Violette on show at the National Gallery.

In 1913, Fergusson met Margaret Morris and they remained partners from that time forward. She was a dancer and both she and her pupils continued to inspire Fergusson, especially the sculpture which the SNGMA reveals was an important part of his work. His circumstances were such that he was never able to make it on a scale to match his ambition, but Alexander Meddowes has one very beautiful wooden figure that is relatively large and very impressive. Also at Alexander Meddowes is a sketch book that Fergusson filled working in the Dockyards at Portsmouth in 1918. The assurance of these drawings translated into a series of strikingly original paintings of the dockyards on view at the SNGMA.

Advertisement

Hide AdWhen Fergusson did first exhibit in Scotland in 1923, it was to show a series of landscapes at the Scottish Gallery that were the result of a tour of the Highlands. The exhibition was a major event. It brought modernism, not just to Scotland, but to the Highland landscape, source of so many of the clichés that bound Scotland to a tacky and imaginary past. It was always Fergusson’s ambition to bounce Scotland into the modern world. It was an ambition he shared with Hugh MacDiarmid and which later brought the two men together. The impact of Fergusson’s Highland landscapes on his fellow painters was also immediate and lasting. Fittingly, one very fine example, Looking over Killiecrankie, is showing at the Scottish Gallery while a group of four hanging together at the SNGMA gives us a sense of how they must have looked in 1923.

Fergusson and Margaret Morris spent the interwar years between London, Paris and the South of France where they had become dedicated (naked) sun worshippers before the First World War. In 1939, however, they returned to Scotland and settled in Glasgow where he sought to encourage modern ideas in a younger generation and she established modern Scottish dance in a legacy that still endures.

• The Scottish Colourist Series; JD Fergusson, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, 7 December until 15 June; JD Fergusson: New Acquisitions, Bourne Fine Art, Edinburgh, until 23 December; La Vie Boheme, Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 4-24 December; JD Fergusson: Unseen Works, Alexander Meddowes, Edinburgh, tomorrow until 10 January. JD Fergusson, Ewan Mundy Fine Art, Glasgow, until 23 December.