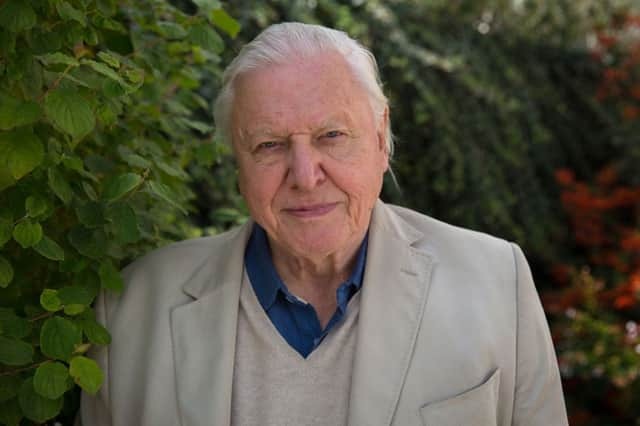

Interview: Sir David Attenborough on following predators

“We thought we knew about polar bears, but there are three completely different hunting techniques which, not only had not been filmed, I don’t think they were known about,” buzzes Sir David Attenborough.

The veteran wildlife film-maker is narrating the BBC’s new landmark documentary series, The Hunt, executively produced by his great friend and collaborator, Alastair Fothergill, who he previously worked with on Blue Planet, Planet Earth and Frozen Planet - and when Attenborough and Fothergill team up, you just know it’s going to be astonishing.

Advertisement

Hide AdAs the title suggests, The Hunt is about predator, prey and the strategies both employ to survive, but it’s not about the kill.

“Every show you’ve seen about predators in the past, they’re always the baddies, they’re the villains, and it’s simply not true, they usually fail,” says Fothergill passionately, explaining how the stakes are much higher for a hungry lion than a hungry zebra, which just needs a patch of grass to munch on, while the lion risks a broken jaw every time it goes for that zebra, “because, quite rightly, the zebra kicks the hell out of it”.

He adds: “They are heroes; they are the hardest working animals in nature.”

But don’t expect scenes of bloody violence and graphic bone crunching. “It’s not a sensational show about predators at all,” promises Fothergill. “David would never touch a show like that”.

That’s not to say that visually it isn’t breathtakingly sensational.

Taking in the vast expanses of the ocean, the jungle and the open plain, where neither predator nor prey has anywhere to hide, The Hunt has been in the making since Frozen Planet wrapped in 2011, with a 30-strong camera crew filming over a period of two-and-a-half years.

Advertisement

Hide AdPacked with never-before-filmed moments, the series sees a Darwin’s bark spider spraying 25m of silk web across a river, Bengal tigers stalking in the forest (a camera was rigged to an elephant to capture it), and the crew even snared footage of blue whales feeding under water - “which is something I wanted to do since Blue Planet,” says Fothergill, still amazed (they celebrated with gin and tonics).

As a result, Attenborough is quick to admit there’s a big chunk of him that wishes he’d been on the ground, not purely working on the words, however much he enjoys that aspect of it.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I saw the first long cut,” he remembers, “and when you see that, you think, ‘Gah, dammit!’ They’ve got these fantastic shots which you never thought was going to be possible.”

Compared to the films being made when he started out (“In the Fifties, it was an amateur half hour really”), Attenborough considers The Hunt to represent a “quantum leap” in natural history programming. “If I was not involved in it - because this is the best - I would be upset,” he says, although he and Fothergill playfully disagree over just how tech-savvy the broadcaster really is.

“It did take us quite a long time to persuade David to get a fax machine,” quips Fothergill.

Attenborough - who, ironically, is the only person to win Baftas for programmes in black and white, colour, 3D and CGI - whips an ancient Nokia phone out of his pocket: “I can show you the cutting edge of electronic communication!”

Joking aside, the challenge on this series was to use technology to get to a point where viewers feel as though they are actually running with a pack of African wild dogs at 40mph, padding along in the footsteps of a leopard, or swimming alongside orcas that are attempting to separate a humpback whale calf from its mother.

The pace is fast, the filming visceral.

“We felt that, if people were to emotionally engage with the challenge, we had to treat it a bit more like a drama than a classic documentary,” says Fothergill, explaining how every sequence was storyboarded. “But of course, the animals don’t read the script.”

Advertisement

Hide AdBoth agree that wild animals - even the deadliest of predators - are rarely dangerous to humans if they’re behaving naturally, but things can always go awry...

“If it wasn’t so dramatic and so serious, it’d be really funny,” says Attenborough, tumbling into an anecdote where, halfway through filming a sequence between a polar bear and a seal in the Arctic, the team “suddenly discovered it wasn’t the seals they were after - the polar bear was actually hunting the film crew.”

Advertisement

Hide Ad“They like seals,” admits Fothergill, “and we’re basically seals on legs, so you can understand that.”

Have they ever felt the urge to intervene, to save one animal over another; to give the gazelle a head start, or help the cheetah clinch its prize?

“There is absolutely no doubt that you see moments like that, but what can you do?” asks Fothergill. “You can’t get between nature.”

“It’s very, very unlikely that you’re going to do any good, and almost certainly you’ll make things worse,” adds Attenborough, remembering footage of an abandoned, orphaned elephant dying of thirst.

“There was nothing you could do, just watch it die,” he recalls with a sigh. “If you’d given it a bucket of water - had there been a bucket of water - what would you have done tomorrow? It’s dying and that’s what the natural world is like. And our job in making these films is showing the natural world. That doesn’t mean to say you don’t feel it.”

Next, Fothergill has plans to focus on the scale of the forces of nature - think volcanic eruptions in extreme close up - while Attenborough has just finished filming a series on the Great Barrier Reef, and has another on bioluminescence lined up. “I’m going to film luminous earthworms in Normandy,” he says with a laugh. “I didn’t even know there were luminous earthworms in Normandy!”

Advertisement

Hide AdDespite nine series of Life on the BBC, 60 years of experience and global expeditions, at 89, he clearly hasn’t lost any of his sense of awe and surprise at the natural world.

“The idea that scientists know everything and understand everything [is ridiculous],” Attenborough says. “I was filming six months ago in Pennsylvania where there are 15 different species of fireflies in one wood, each transmitting its own luminous call sign. Talk to a biologist and he simply won’t understand how there could be that number. Why are there so many different ones? We don’t know!”

Advertisement

Hide AdSimilarly for Fothergill, the amount of creatures still left to discover and understand is unfathomable. “More people have walked on the moon than been to the bottom of the deep ocean,” he says reverently. “We’re never going to run out of stories.”

“I can’t believe I’ve been as lucky as I have,” reflects Attenborough, considering all he has done. “It’s the most exciting thing I’ve ever wanted to do, and to keep on doing it when you’re damn nearly 90 is a huge privilege, a huge piece of luck - and it’s not virtue, I’ll tell you that. It’s not because I’ve run round the park every day.”

So will he ever retire?

“If Alastair asked me to do something, I’d do it - if I could get there in the wheelchair.”

• The Hunt begins on BBC One on Sunday, November 1