History of fashion, from loincloths to Louboutins

“You think this has nothing to do with you,” she snarls. “You go to your closet and you select… I don’t know… that lumpy blue sweater, because you’re trying to tell the world that you take yourself too seriously to care about what you put on your back. But what you don’t know is that sweater is not just blue, it’s not turquoise. It’s not lapis. It’s actually cerulean.”

She goes on to describe how that colour first appeared on the Oscar de la Renta catwalk, then was featured by Yves Saint Laurent. “That blue represents millions of dollars and countless jobs and it’s sort of comical how you think that you’ve made a choice that exempts you from the fashion industry.”

So, we underestimate fashion at our peril.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Fashion has often been dismissed as a trivial or frivolous subject, unworthy of serious attention,” says the museum curator Valerie Steele, in the foreword to Fashion: The Whole Story. “This could hardly be less true. Far from being a whirligig of meaningless change, fashion is a crucially important part of modern society and culture.

“Fashion touches on many aspects of life,” she continues, “including art, business, consumption, technology, the body, identity, modernity, globalisation, social change, politics and the environment.

“Fashion is also a multi-billion-dollar global industry, employing a vast international labour force. Indeed, we might better think of it as a network of industries, since the fashion system involves every activity, from the production of raw materials to the manufacture, distribution and marketing of a wide range of fashions – from couture ballgowns to blue jeans.”

“Fashions change for the same reasons we’re not just watching Shakespeare any more,” says the book’s editor, Marnie Fogg. “People like change. There are huge innovations in technology, which account for massive changes in fashion. Without the invention of starch we wouldn’t have got the Elizabethan ruff; without the invention of tights we wouldn’t have had the mini skirt. But, basically, it’s the human desire for change. We seek novelty in life, whether it’s TV programmes, or what you’re going to see at the cinema or the theatre.”

But she mockingly rejects that old chestnut about hemlines reflecting the state of the economy. “I think that’s slightly spurious. Fashion just marks the progress of ideas. We use it to define ourselves. As we change, we change the clothes we wear. We might be an ingenue in our teens then we become much more interested in classic clothes, or avant-garde; fashion represents how we want to appear to the world.

“I don’t know any business that works as hard as fashion designers,” she adds. “They no longer just do two seasons a year – autumn/winter and spring/summer – they now have to do pre-fall, resort; it’s a continuous thing because people, in spite of recession, do desire the next new thing.”

Advertisement

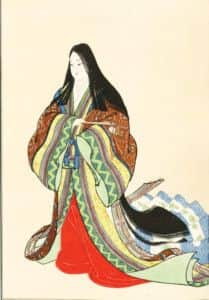

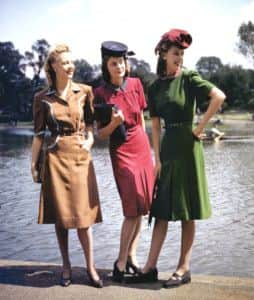

Hide AdThe book is laid out chronologically, celebrating the progress of fashion, from Greco-Roman woven clothing (which was so expensive and precious that to cut it and tailor it was considered wasteful, resulting in the draped, free-flowing garments we recognise from statuary and frescoes) to the silk court dress of the Chinese Tang dynasty, through the dandy, the crinoline, the flapper dress, Le Smoking and Biba, right up to the era of the supermodel. But, for Fogg, who is also author of Boutique: A 60s Cultural Phenomenon, the 1960s were, by far, the most interesting period.

“I was slightly too young for the mod thing, but I was definitely a hippy,” she says. “It was part of that counter culture, of rethinking clothes and young people getting clothes that were specifically designed for them by their friends. It was a unique period, the post-war, baby boom 1960s.”

Advertisement

Hide AdSomewhere between cavewear and couture, however, fashion became big business rather than just a cultural and historical phenomenon.

“You had the dressmaker who became the couturier,” says Fogg, “but I think it’s generally regarded that the industrial revolution is where it all started, because that’s when you had the introduction of the sewing machine and factories – Smedley, for instance, the knitwear factory, began in the 18th century, as did Pringle – so that saw the beginning of the fashion industry rather than the fashion designer.”

And as that industry has grown, the relationship between designer, buyer and client has changed irrevocably. “Now you can buy direct from the catwalk, with live streaming. Burberry was first to do that,” she says.

Ultimately, though, it is not the customer nor the designer who is in control; it is the conglomerates – giant businesses such as LVMH, which owns Marc Jacobs, Celine and Givenchy as well as Louis Vuitton, and PPR, which recently bought a majority stake in Christopher Kane and whose portfolio also includes Stella McCartney, Alexander McQueen, Balenciaga and Gucci.

“They just eat up the new designers they take on board,” says Fogg. But she adds that, rather than killing creativity, they exploit it and, ultimately, validate it. “These big brand names – like Ungaro and Givenchy and Yves Saint Laurent – they are desperate to keep their heads above water and to stay ahead of the game. Ten years ago students were grateful to be taken on board by them, but I think it’s different now – you have people like Christopher Kane saying no thank you to Versace, they want their independent label.

“So in a way, the conglomerates exploit that creativity and eventually validate it. Once people like Christopher Kane have made their name as a designer, they are bought up and it allows them to become a big brand.”

Advertisement

Hide AdThe way we follow fashion, too, is changing. Where once the clothing we wear was driven by practicality or industrial progress or sexual freedoms, now it’s all about the blogger. “In the 1960s,” explains Fogg, “you had street fashion, in the 1970s and 1980s you had punk, now trends are very much influenced by the bloggers – they are much more influential than the fashion editors.

“The parameters have changed too,” she adds. “I think what you might consider safe now might have been considered extraordinary in the 1970s. I don’t think people are shocked any more; no one finds fashion risible anymore.”

Advertisement

Hide AdShe recalls Vivienne Westwood appearing on the Terry Wogan show wearing a mini-crini. “Everyone was thinking it was a real hoot. She said: ‘If you don’t stop laughing I’m going to get up and walk off the set.’ But I don’t think people find fashion risible in that way; I don’t think anything is seen as funny or peculiar or odd. Only the very extreme. In fact, I’m in the middle of writing a book called You Can Go Out In That, because there really are no limits.

“What starts off as marginal then becomes mainstream,” she says. “You had the Westwood T-shirts with slogans that were considered obscene, and the bondage trousers and all that fetish stuff, then Zandra Rhodes goes and does a lovely pink crepe dress with safety pins and it becomes mainstream, and that’s invariably the case with fashion.”

Twitter: @Ruth_Lesley

Fashion: The Whole Story, edited by Marnie Fogg, is published by Thames & Hudson, £19.95