Film reviews: I Am Not Your Negro | The Boss Baby | City of Tiny Lights | Table 19 | Neruda

I Am Not Your Negro (12A) *****

The Boss Baby (U) **

City of Tiny Lights (15) **

Table 19 (12A) **

Neruda (15) ***

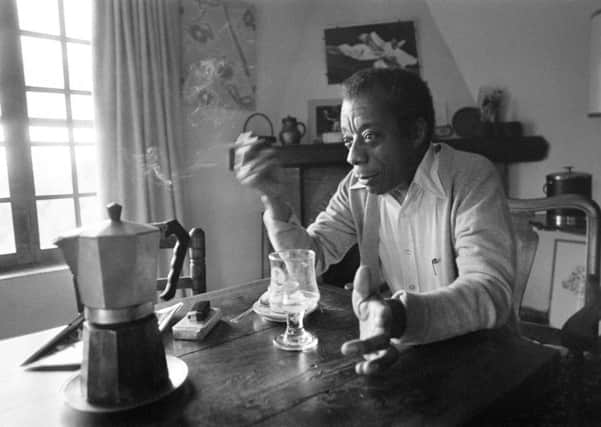

One of this year’s Oscar nominees for best documentary feature, Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro uses the writing of the late James Baldwin to explore the story of race in America – a subject that, as Baldwin once remarked, is inevitably and inescapably the story of America itself. Beginning with Baldwin’s abandoned book about the murders of civil rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King – all friends of Baldwin’s, all slain before they were 40 – the film uses a wealth of archival footage and incisive extracts from his literary output (Peck was granted full access by Baldwin’s estate) to bring to life a centuries-old struggle that’s really no closer to being resolved, something evidenced by the way Peck cleverly juxtaposes Baldwin’s words with choice footage of Rodney King, the Obama inauguration, Ferguson and more.

Baldwin himself was a literary exile during the early parts of the civil rights era, living in Paris where he was able to find the headspace to write – an advantage of no longer having to contend with the very real threat that being black and gay posed to his life in America. But out of a sense of duty to the cause he returned in the 1960s and became a prominent intellectual and spokesperson – someone, he notes drily at one point, to whom the Malcolm X-fearing white establishment could turn. But as the film illustrates, he also knew he and Malcolm were trapped in the same situation and his writings on race in the proceeding years elucidated the complex realities of an inherently racist society in ways that don’t just resonate today, but seem increasingly relevant and urgent. The film is also a fascinating essay on representations of race in the media, and cinema in particular, with Peck drawing heavily from Baldwin’s 1976 book on movies, The Devil Finds Work, to explore the ways in which so many films about black lives are designed to reassure white America. Featuring a nuanced readings of Baldwin’s work by vocal Samuel L Jackson, it’s an astonishing piece of filmmaking: engrossing, intellectually rigorous – and depressingly timely.

Advertisement

Hide AdThere are some crazy theories doing the rounds that the big new animated kids’ film The Boss Baby is stinging satire of Donald Trump. It’s not. Sure, it may be amusing to think of a film in which a petulant, business-suit-wearing baby disrupting the harmony of his new family is a sly metaphor for America’s 45th President and the havoc he’s wreaked on the world since taking office. And yes, the casting of Alec Baldwin as the voice of said baby lends an extra frisson of playfulness given he’s currently to be found mocking Trump on a weekly basis on Saturday Night Live. But Baldwin’s casting owes more to his iconic performance in Glengarry Glen Ross than any real foresight on the part of the filmmakers and the satirical implications are more the result of grasping-at-straws columnists who’ve perhaps read the premise but likely haven’t actually had to sit through this rather weak and nonsensical family film. The main problem is that in (loosely) adapting Marla Frazee’s 2010 picture book, the notion of a pre-teen sibling viewing the arrival of his new baby brother in terms of a hostile take-over over-extends a brilliant short-film idea into a gibberish, over-complicated and desperately unfunny feature.

The idea of Riz Ahmed as a chain-smoking, bourbon-drinking London private eye is so flat-out intriguing it makes the general incompetence of City of Tiny Lights all the more disappointing. Directed by Dredd’s Pete Travis, the film sabotages Ahmed’s undeniable star presence with reams of terrible dialogue, inept voice-over, visuals that aren’t so much noir as flat-out murky, and way too many tedious childhood flashbacks designed to fill us in on Ahmed’s not-very-interesting relationship with Billie Piper’s restaurant manager, who, thanks to an obvious budget shortfall, appears to only own one dress. What a waste.

Also wasting a great cast is Table 19, a misfiring indie comedy/drama in which Anna Kendrick, Lisa Kudrow, Craig Robinson, June Squibb, Stephen Merchant and Tony Revolori play wedding attendees who’ve been consigned to the misfit table at the reception. Kept far away from the happy couple, they inevitably start to bond over their swiftly acknowledged status as social pariahs. Alas, any comic or dramatic potential is squandered by writer/director Jeffrey Blitz, who mixes pratfalls and mistimed declarations of love with sentimental revelations involving terminal illness and unwanted pregnancies. Like the bride and groom, you’ll want to keep your distance.

By contrast, Neruda sees Jackie director Pablo Larraín deliver another intriguing portrait of political power and myth-making, this time in the form of a biopic (or rather anti-biopic) of Chilean poet and Communist politician Pablo Neruda (Luis Gnecco), who was forced to go on the run in the late 1940s as Chile’s political establishment lurched to the right. Larraín establishes some of the facts of Neruda’s life, but in keeping with his subject’s poetic side, he invents whole swathes of the story, including the film’s narrator, a whip-thin police inspector named Óscar Peluchonneau, who’s played by Gael García Bernal and is dogged in his pursuit of Neruda. Such meta flourishes interrogate the notion that art is sometimes the only way to ensure history is preserved when those in power seek to rewrite or erase large chunks of it. For all its ambition and scale, though, it feels like minor work.