Darren McGarvey interview: ‘I’m still in close proximity to the quicksand’

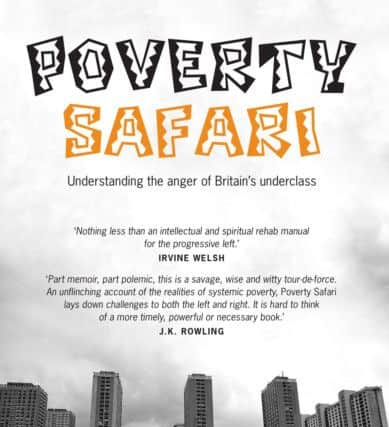

We’re in a light-filled yurt at Edinburgh International Book Festival, the aroma of coffee rises from the mugs on the table and the murmur of conversation and applause from various tents drifts through the canvas. For Darren McGarvey this is familiar turf – he’s been here before with his breakout book, 2017’s Poverty Safari, which won him the Orwell Prize the following year.

The author, broadcaster, activist, social commentator, aka as hip-hop artist Loki, now 35, has come a long way from his youth in Pollock on Glasgow’s south side, and yet he hasn’t. Whether leading workshops in prisons or private schools, sitting down in the street with a homeless person, with the First Minister, or in a Book Festival yurt, he’s still burning with the need to confront the issues that have always concerned him, that formed him: inequality, injustice, poverty, and its effects.

Advertisement

Hide AdThat’s why he’s on our TV screens with Darren McGarvey’s Scotland, a six-part series on BBC Scotland in which he takes TV cameras across the country to meet the people who feel the impact of poverty most. As he puts it in the series introduction: “I want to immerse you in the world I grew up in... A world defined by poverty.”

With poverty as the common denominator, McGarvey’s aim is “to put the contributors front and centre and let them lead the narrative”. In Dundee he meets those living with its European drug death capital statistics, in Edinburgh sees how a young mum fights the effects of sub-standard housing and explores the links between poverty and crime and in Dunbartonshire he hears how it impacts women’s safety. In Glasgow he meets the men destined to die younger than those anywhere else in Europe, explores rural poverty and mental health issues in the Borders and in the country’s oil boom capital, Aberdeen, meets those out on the streets.

The effects of poverty are only part of the story, as McGarvey highlights how people in the hearts of these communities are fighting back with grassroots solutions. He takes us to a scheme to get young people away from street crime at night in Edinburgh’s Pilton, a project to provide women and girls with sanitary products, gets in step with line-dancing ‘grannies’ in Glasgow’s Possilpark and discovers horse-riding therapy in the Borders. There’s a rap workshop with prisoners at HMP Edinburgh and food banks in Aberdeen, where staff include offenders carrying out community service.

Where McGarvey’s series has the edge is that when it comes to poverty and living in it, he knows from personal experience what he’s talking about. In Poverty Safari McGarvey, as well as voicing the anger of those living in poverty and what he thinks could be done to change it, writes about his struggle around drugs, alcohol, and mental health issues, and his alcoholic and drug-addicted mother’s early death at the age of 36. As he says in the series, “I know as well as anyone, what damage alcohol and substance abuse can do. I’m a recovering alcoholic and drug addict, who’s often struggled to stay sober.

“I understand it intimately and because I come from these communities and have experienced many of the issues, I can make someone feel comfortable quickly and in a genuine way.”

McGarvey has an ability to allow people to speak for themselves on film which gives the series an authenticity.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Letting someone know they don’t have to go any further if they don’t want to makes them comfortable enough to lay the issues out and they begin to show a humanity, intelligence and sophistication not normally associated with this demographic on TV.

“I want to show working class or lower class culture is not necessarily a more primitive form of middle class culture, but a parallel, that contains all of its own wisdom, humour, distinct experiences and must be recognised as equal, not necessarily financially, but in terms of social standing and understanding where people come from and why they form the beliefs they do. There is a great deal for us to learn from the wisdom of people who struggle and the adaptations they go through to navigate that and help themselves and others.”

Advertisement

Hide AdWinning the Orwell Prize for Poverty Safari gave McGarvey the chance to move from writing and appearing on TV and radio to steering a show himself. However, it was crucial for him that it was different from other programmes on the subject of poverty.

“I’m just not happy with the quality of programming about poverty on television full stop. A lot of previous content, well meaning as it’s been, like The Scheme or Benefits Street, leaves ethical questions unanswered, doesn’t devote enough time to the socio-economic context of the dysfunction they’re always parading.

McGarvey wanted to do something within the genre but also “look at the quicksand these people are stuck in rather than just focusing on personal behaviours. What’s the engine room of the behaviour? Why does it arise? Is it something to do with the environment? If we want to modulate behaviours, we need to change the environments.”

Raised by an electrician father after his mother left when he was about ten, McGarvey and his siblings grew up in a house filled with guitars, art and music, and was encouraged by his father to pursue whatever he wanted to do.

“My mum educated me in different ways, in the ways of the street. She came from an environment where survival was the thing; if you show weakness somebody’s gonna take advantage so don’t back down, if somebody gets the better of you let them think they’ve won then circle back and get them later, and make sure everyone sees you do it. Don’t let anybody talk about your family, don’t let anybody take the piss. You know, those morals and values might seem kind of primitive to some, but there are middle class iterations of all of them which by virtue of that have less stigma attached.”

These days McGarvey lives in East Kilbride with his fiancée, their three-year old son and one-year-old daughter, and with a prize-winning book under his belt and a career as a broadcaster, journalist, writer and activist, another successful show on this year’s Edinburgh Fringe, the BBC TV programme and another book on the go, he’s very aware of the change in his circumstances.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“In the last 12-18 months I’ve shot up a few tax brackets, and I’m experiencing a lot of the ways I could change if I allowed myself to,” he says, “but luckily I still retain vivid memories of what it’s like to struggle.

“The things I’m saying haven’t changed but the social vantage point from which I speak has, so I have more ownership over everything I do now, more authorship, more autonomy. People further down the food chain don’t have that narrative and value. It’s constantly extracted from them, not necessarily deliberately, like Benefits Street, and sometimes deliberately, like the Jeremy Kyle Show.

Advertisement

Hide AdSo would he describe himself as middle class or ABC1 now, like the audience at his Fringe show which he’ll perform after leaving the yurt?

“On paper obviously, I can’t deny that. I was talking to Akala about this [he and the rapper performed together] because he’s going through a similar transition. About the fact you’re always travelling but can’t moan because you’re very privileged, about left-wing academics who seem affronted we have the gall to speak on behalf of ourselves and not be mediated by the wisdom of the intelligentsia, and that no matter how much money you make or how successful you are, your class is defined by your social connections.

“So it doesn’t matter how many friends I make in journalism, the literary world or television, I’m still close in proximity to the quicksand. I’m the most affluent person in my family now but one relapse, one poorly judged tweet and I get a sense of the fragility of my social position. Class is not necessarily defined by what’s in your bank account, but by how stable your position is, and a lot of my social connections, family and friends are still living the way I was before.”

That evening, his new live show on the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, entitled Darren McGarvey AKA Loki: Scotland Today, a follow-up from last year’s hit Fringe show, Poverty Safari Live, sees him give his own take on the state of the nation in a mix of spoken word, comedy and music. Hard-hitting, edgy and humorous, the show reflects on what has changed for McGarvey and he uses this to zone in on the ‘insulated’ ABC1s in a bid to wake them up to the need for change.

Starting with some rapping from Loki it moves on with McGarvey in suit and glasses, every inch the ABC1 talking about inequality and what happens when idealists are bought off. Then three-quarters of the way through, there’s a rug pull moment and he transforms into his former self in baseball cap and joggers, telling us what Darren REALLY thinks about the ABC1s calling all the shots. For McGarvey this is the optimum way to challenge his audience – let them think they’re winning then go round the back and get them, as his mother might have said.

“For me to come out and talk that frankly, a lot of people would become disengaged. So you’re inviting them in, saying, hey, I’m middle class as well, ain’t it great, and then you take a wee turn and say, but… And then it comes to the last third and it’s, OK you’re ready now for the onslaught.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I say to ABC1s, to myself, don’t beat yourself up, we’re all products of our environment, we just need to bring to bear a wee bit more awareness of how complicit sometimes we can be, because that’s the beginning of change. After 18 months of living in relative prosperity, if I can forget what it’s like to be poor, what chance is there of people who have always been middle class, or god forbid, the Theresa Mays and Boris Johnsons of this world to understand it?

“The show is a reflection of a move away from the analysis of my own poverty into an analysis of prosperity, which brings it closer to home for a lot of the audience I’ve gained through the book, who are always commending me for brutal, harrowing honesty. Are they interested in honesty when it’s talking about the honesty of middle class privilege and the political and social implications of it?”

Advertisement

Hide AdMcGarvey’s aim in his work – the live show, the series, his books – is to speak to this duality he sees within those who say they want a fairer society, yet when it competes with self interest, square it through self-delusion.

“The things we tell ourselves about meritocracy and social mobility that justify why we’re a winner and they’re losers don’t stand up to scrutiny. They are self-soothing ideological tonics that function in much the same way as the illicit drugs people in Dundee are dying from. They take the edge off reality, help people push difficult truths down.

“If you’re deluded enough to think someone like Boris Johnson got where they are because of their own endeavour you’ll believe anything. We’re all products of our environments and circumstances. I always try to remind myself of that because it’s very easy to start thinking ‘look at me’, ‘look at what I’ve done’. I wouldn’t have won the Orwell Prize if my publishers hadn’t entered on my behalf because I was too frightened at the forms.” He laughs. “I still don’t really believe it to be honest, I’m waiting for them taking it off me.”

The Fringe show is “a synopsis” of McGarvey’s next book, which he’s working on now. “It’s market research really, to see if middle class people are still going to want to buy my stuff.” He expects the book to be out in the spring, despite having rewritten it four or five times.

“I keep trying to write another book because I thought with this one, I don’t want to piss off the ABC1s, every time I sat down.”

The ABC1s aren’t pissed off at the Fringe, I say, if the show I saw is anything to go by.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“It’s easy to say that,” he says, “but when you’re the one putting everything on the line, you’re a wee bit more cagey. But I decided just to go for it. I think it’s honesty that people appreciate.”

McGarvey is fast talking and articulate. Ask him a question and he gives full and complex answers that have me struggling to keep up. In fact he can answer different questions at once while segueing into relevant asides such as – “I’m a bit ADD, you know, I was diagnosed as ADD by Gabor Maté, a very well-known trauma specialist and addiction specialist at an event in London”. But when I ask him what he would say to his younger self, the Darren that comes out in the live show, or the anxious child scared of his unpredictable mother, for the first time he is lost for words.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Em…” There’s an uncharacteristically long pause then he says:

“I would probably tell myself to worry less... stay out of your own head. It’s a tremendous burden when we get caught up in the nonsense our head tells us. Meditate more, think more about other people and that private burden is reduced. So just… aye, don’t worry so much.”

At the moment McGarvey is in a good place, unlike last year when four year’s work in one left him strung out, with the series also taking its toll when McGarvey found himself back in familiar terrain.

“The gravity of poverty still bears down on you, even when you’re not poor any more, so imagine how it would feel if you never escaped? Being back in those environments triggered a lot of things for me – and I was just going in with a film crew!

“I like the broadcasting, but it’s 12-14 hours some days, travelling, and that’s cool if that’s the only thing you do, but I also always have a book to write, a show to write, and a family with two small kids. Sometimes I’m pulled in so many directions it can have an impact on my well-being and mental health. As much as you get celebrated as someone who has transcended all their difficulties, the last year for me has been very challenging, because there’s an identity crisis when your social position changes, and there’s this mad drive to grab all the opportunities.”

But McGarvey isn’t complaining, as being financially liberated gives him the freedom to address other areas of his life, such as his family and lifestyle.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I’m healthier than I’ve ever been,” he says, “and able to dedicate more time to thinking about what I eat to sustain my energy levels and have kids, and all that sort of stuff. So far so good. I’m always a work in progress.”

He stands to go, time for photographs, and framed in the doorway, occupying a liminal space between two worlds he turns, smiles and says:

Advertisement

Hide Ad“There’s no brick walls with graffiti on them round here, don’t know how you’re gonna get a picture.”

McGarvey has left the yurt.

Darren McGarvey’s Scotland continues on BBC Scotland on Tuesday at 10pm. The first episode is available on the iPlayer