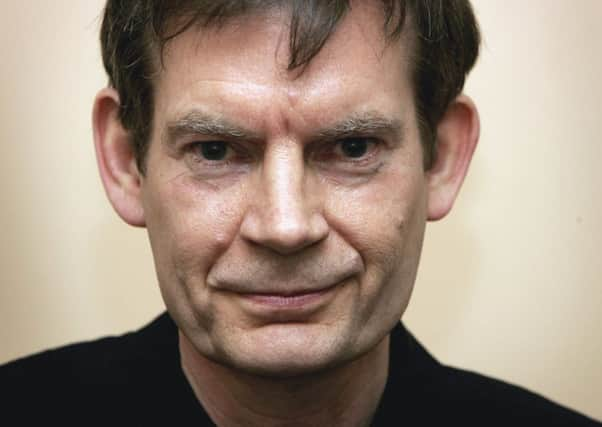

England and Other Stories: By Graham Swift

England and Other Stories

By Graham Swift

Simon & Schuster, 274pp, £16.99

Graham Swift is a master of the short story, and this collection is full of gems. This is not to say that it will delight everyone. If your idea of a good short story is an anecdote with, perhaps, a twist in the tail, the kind of story that Maugham and Maupassant wrote so well, then Swift is not the writer for you.

His stories are more like Chekhov’s or William Trevor’s. They are snatches of seen and felt life. The narrative is usually veiled, the movement internal. He fastens on a moment of his characters’ lives and explores its significance. There is nothing flashy about the stories, whether he is writing in the first or third person, but he has a wonderful knack for getting the tone right either way. He can inhabit the mind of a Cypriot barber long resident in England or a lawyer who has just received a death sentence from his doctor, and find the right convincing voice for both of them.

Advertisement

Hide AdHe can encapsulate lives in a dozen pages, with keen sympathy. Take the story “Yorkshire” for example. Daisy, an elderly woman, lies in bed, not sleeping, as she didn’t sleep 50 or more years ago when she knew that Larry, her fiancé, was a wireless operator in bombers flying over Germany. Now she can’t sleep because Larry is going – “voluntarily” – to a police station in the morning, “to clear this matter up”, and, because he thinks “this matter” has corrupted their relationship, he has gone to sleep in the spare bedroom.

The “matter” is their 48-year-old daughter Adela’s allegation that her father abused her when she was a little girl. Daisy found herself surprised by “the fierceness and quickness of her answer”. “She hadn’t been lost for words exactly, or for a way to say them. She’d spoken in a certain voice and with a certain look. She knew she had a certain look, because Addy had actually stepped back.” She finds herself, frighteningly, in “that area where memory itself stopped and no-one could say what was true or false.” Swift recognises that what we believe to have happened, or not happened, may have its own truth. People are complicated; he never allows us to forget that.

In “The Best Days” two young men, six years after their school days, attend the funeral of their old headmaster. A girl, Karen, whom they both fancied, turns up with her father (who has clearly come straight from the pub) and mother, who is dressed as tartishly as the daughter. “‘She looks a right old baggage,’ Andy said.”

His words embarrass and irritate his friend Sean, who has memories which are themselves embarrassing, but also pleasant, even exciting. There is indeed a lovely teasing twist to the tail of this story, but it wouldn’t be in any way effective, if you recounted it in your own words. In Swift’s telling it is funny and also sad.

He has a nice way with a cliché, as an arresting opening: “When Aaron and I were young,” one story opens, “we used to chase women. It’s a phrase. How many times do you actually see a man chasing a woman, say ten yards behind and gaining. We were both runners anyway, literally – athletes”. You are drawn in straightaway, curious about the races they may have run, they women they may have caught or failed to catch.

Swift’s range is considerable. One story, unusually, is set in the deep past, involving a letter purporting to be from Charles I’s physician, William Harvey, famous for discoveries concerning the circulation of blood. It’s a bit of an oddity, but one that comes off.

Advertisement

Hide AdMost, however, are set in today’s Middle England, a country always changing, yet retaining its connection to the past. Swift is as comfortable writing about immigrants as about a Wapping boy with a head for heights, who prospers by setting up a company to clean the windows of the glass towers of Dockland, or in the title story, recounting a meeting on Exmoor between a coastguard and a stranded motorist who turns out to be a stand-up comic of West Indian extraction. There is pathos, and also much to admire, in his inability to converse except in terms of his stage-act which takes him to one-night gigs all over the country.

He also understands the modesty that demands privacy: a man in late middle-age pushing the daughter of his second marriage in a baby buggy fends off a fierce dog attacking another small child and finds that “he very much wanted it to be as if nothing had happened”.

Advertisement

Hide AdSwift has never achieved the celebrity of some of his contemporaries who were selected alongside him in the first famous Granta list of the best young novelists some 30 years ago. I daresay he wouldn’t want such celebrity; I am sure he is better off without it, and a better writer because he has been spared it. He is one of those who looks at life with a sympathetic eye, who tells us, convincingly, how people of all sorts live from day to day, sometimes lives that are rewarded with happiness, sometimes lives of a quiet, even heroic, desperation. He is a writer to savour and enjoy, and we are lucky to have him.

Graham Swift will be talking about England and Other Stories at the Edinburgh book festival on Tuesday 12 August