The Boyle Family come full circle

I’M SITTING with the Boyle Family in a cafe on the corner of Woodstock Street in central London. The location is significant. Fifty years ago, in the building across the street (now an estate agent’s), Mark Boyle and Joan Hills had their first exhibition.

Hills and her children, Sebastian and Georgia Boyle, want to show me where it all began, to draw the unbroken line from that show till now when, continuing to work as Boyle Family eight years after Mark’s death, they are preparing to open a show of new work in the Vigo Gallery a couple of streets away. “It’s very interesting that we’re still here – we’ve just gone round the corner,” says Sebastian.

Advertisement

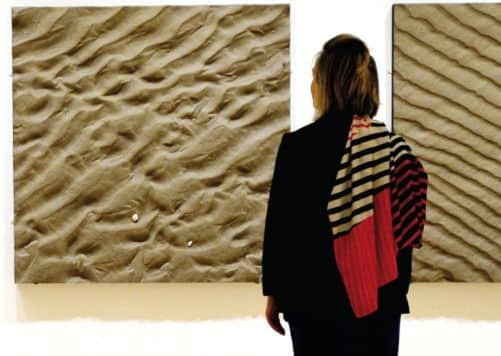

Hide AdMeanwhile, a seminal work from 1969, the Boyles’ Tidal Series, will be displayed by the National Galleries of Scotland in a show of recent acquisitions. Last seen at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in 2003, it comes from a key period in which the Boyles established their modus operandi and became recognised as ground-breaking conceptual artists.

But in the cafe we’re all conscious of an absence. Mark Boyle was the raconteur of the family, the weaver of yarns. Sebastian is chief spokesman. His sister is taciturn, watchful, occasionally acerbic. Joan is warm, funny and charming. By the time we leave she virtually has a date with the cafe owner, who would doubtless be as surprised as I was to learn that this svelte blonde won’t see 75 again.

The Boyle Family are pleasant company, generous and gregarious, yet some questions remain unanswered. They don’t describe the techniques by which they achieve their sculptural panels which mimic perfectly the surface of the Earth. And they never fully explain the nuts and bolts of the family collaboration.

Instead they tell the story. Mark Boyle met Joan Hills in Harrogate. He was in the Scots Guards, writing poetry, on the run from a law degree in Glasgow. Edinburgh-born Joan, three years older, was trying to paint. Within hours they had decided they would work together for the rest of their lives.

They moved to London, creating sculptures and assemblages from junk found on demolition sites. After the show at the Woodstock Gallery in 1963, they took the show to the Edinburgh Fringe where they helped stage their first happening with American artist Ken Dewey, and were nearly prosecuted over the presence of a nude woman. They returned to London with enough kudos to propel them into the counter-cultural scene. They produced sound-and-light shows for UFO nightclub and toured the US with the band Soft Machine, supporting Jimi Hendrix.

Sebastian, born in 1962, and Georgia, born 18 months later, have struggled to answer questions about when the collaboration started (the name “Boyle Family” was adopted in 1985, but the concept was much older). It was Mark’s illness – he suffered a stroke in 2004 – that gave them their answer. “It took Mark months and months to recover,” says Sebastian. “We were facing a situation where Mark might not recover to be able to work with us. And there was no way we were ever going to kick him out of Boyle Family, even if all he could do was sit in the wheelchair. We all realised immediately the circularity of our family history. Mark and Joan said for years that their lives changed completely when Georgia and I were born. Even when we were only months old, we were actually contributing by changing things.”

Advertisement

Hide AdThe common thread which runs through all Boyle Family work is observation, the intensity of looking at what is in front of you, whether that is an enlarged microscopic photograph of a hair, a teardrop trapped in a slide, or a patch of waste ground. Their work changed when they found the plastic surround of a television screen and began to use it to “frame” the ground. Between 1967 and 1969, they asked blindfolded visitors to throw darts into a world map, giving them 1,000 random locations. These would be their World Series. It continues to be their lifework.

Meanwhile, they made the Tidal Series, decamping in November 1969 to Camber Sands on the Sussex coast. There they made meticulous sculptures of the same patch of sand, twice a day, charting the effects of the tides, and pioneered their use of fibreglass and resin. The series was bought by their friend and patron, Sir Peter Moores, whose Foundation recently gifted it to the National Galleries of Scotland.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I remember being very cold and very wet,” says Georgia of that November on the beach. “And lots of very hard work. Although we were very tiny, we were nevertheless expected to do our bit.”

Sebastian adds: “We wanted to be involved, like my five-year-old wants to be involved in whatever is going on in my house now.”

The following year, the family made the first World Series piece in The Hague, then headed for Norway in a reconditioned ambulance. “That was our upbringing,” says Sebastian. “If there was a big show we would be off, and luckily we were at a school where the headmistress thought it was a really good education.” In 1978, he finished his O Levels just in time to join his family at the Venice Biennale.

Home in London was a succession of flats chiefly chosen for their suitability as a studio. Joan says: “I remember Georgia coming home from junior school, having been at a friend’s house, and she said ‘The funny thing is, Joan, they had furniture, they didn’t have sand and rocks in the corner.’” She laughs heartily. “I didn’t think it was quite as bad as that, you understand.”

Family life was inseparable from the making of art, and so a way of working evolved in which everyone had a veto on every decision, and flaming rows were instigated about colour matches. “But one of the great things about working with resin is, once the hardener is in the bucket, it’s going off, you’ve got a fixed amount of time to get this done and there’s no second go,” says Sebastian. “Finally, you’re all happy to go with it, and you get that period of just total concentration and enjoyment. That is a great way of living.”

They have made World Series artworks in New Zealand and the island of Vesteralen in the Arctic Ocean, on a beach in Barra and on the pavements of New York. The latest piece, to be unveiled this month, is a patch of dark, dry earth from the Lazio region of Italy.

Advertisement

Hide AdThese days the Boyles take fewer risks. “You suddenly realise, having been in quite a few dangerous situations [Mark setting off on skis in Norway into a whiteout, and breaking down in the Outback in Australia and being rescued by Aboriginals], that it’s actually quite easy to do that,” says Georgia.

Mostly, however, on the job they are ignored. “People pass you without looking because you’re wearing an orange or yellow jacket,” says Sebastian.

Advertisement

Hide AdHow has it been to carry on without Mark? “We spent so much time together and got to know each other so well that, in a funny way, it prepared us for the time when we weren’t all together,” says Sebastian. “We don’t have any regrets, we don’t say ‘We wish we’d spent more time together’. It would have been hard to spend more time together! Mark had his great sides, and just enough flaws to let you know he was a human being. “We would all love Mark to be here, would love Mark to be seeing this exhibition. If Mark were here, we’d all be driving each other nuts now. With two weeks to go, we’d be saying: ‘We need to start making the work now!’” n

• New Acquisitions is at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, until 1 March. Contemporary Archaeology: The World Series Lazio Site, 1968/2013 is at Vigo Gallery, London, from Wednesday until 16 November