Book review: The Dance Of Death: A Vanitas, by Martin Rowson

Each of the illustrations, as with the Holbein, are accompanied by terse verses. The conceit is quite simple. We are all corpses in waiting, and DEATH (referred to here as both he and she, but always capitalised, which seems a nod to Terry Pratchett’s depiction of the Grim Reaper) is a certainty. The little poems have a whiff of the clerihew about them, although they rhyme A-B-A-B, but what they brought to mind most was Hilaire Belloc’s Cautionary Tales For Children. I had forgotten how, as well as the Roald Dahl-esque horribleness in Belloc, there is a vinegar-sharp critique of politics (from Lord Lundy, on his being demoted, “Sir! You have disappointed us! / We had intended you to be / The next Prime Minister but three: / The stocks were sold, the Press was squared / The Middle Class was quite prepared. / But as it is!... My language fails! / Go out and govern New South Wales”.)

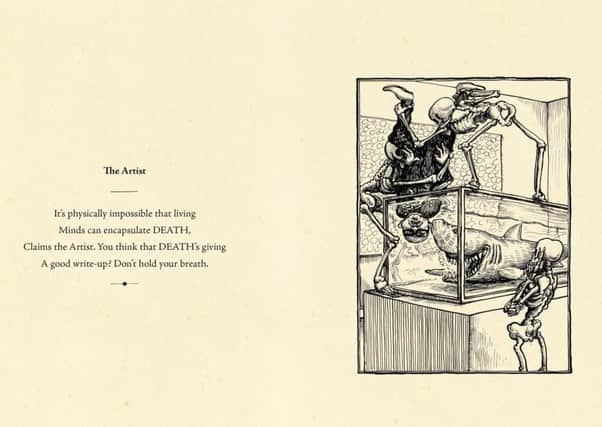

Rowson’s verses have the same tang to them, as in, for example, The Keyboard Warrior – “The fearless Keyboard Warrior / Sends DEATH threats out by tweet / DEATH makes sure he’ll be the sorrier! And so she pressed DELETE”. Or The Priest: “The Priest will intercede with God / Then go and write a column / Till DEATH turns up and makes the sod / Appear a lot more solemn”. As you can see, each verse depicts a type, in the same way Holbein did. But what makes this far more intriguing and re-readable is that the verses don’t specify the particular individual that Rowson’s wrath has lighted upon. The images, however, certainly do. I don’t know if that is a legal defence against defamation, but it is a very clever way of making the book both topical and apocalyptic and actually moral. Indeed, the fact that one of the pairs of poem and illustration deals with The Cartoonist shows there is a levelling throughout the book. Unless you’re willing to depict yourself in the harshest light, and this is certainly one of the most grotesque of the images, you have no right to call out anyone else.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe illustrations are pure homage to the Holbein original (which has been recently republished as a Penguin Classic, so you might care to buy both and play compare and contrast). The capering skeletons in Rowson’s work are close cousins to the Holbein. They are in an awful way gleeful, even smirking (difficult to do without lips), with reprimanding fingers. But they also looked bored, raucous, jubilant and strangely sad. The reader needs to take time over the images. It was only on my third or so read of the book that I realised that in the picture of the expulsion of Adam and Eve into the world of death, DEATH is texting on his mobile phone. But the sneaky joy of it is linking the generalised title to the specific reference. I’ll leave it to readers to guess whose phizog goes alongside The Clown, or The Ponce, or The Editor” That final one is beautifully clever, making it absolutely clear which former newspaper editor is being referred to, but shambling the paper itself into paper-chains where you can piece together some notorious headlines.

There is a kind of necessary connection between satire and this kind of work. Holbein was working in woodcuts – it was cutting. Later satirists, such as Hogarth, used engraving, another form of incisive action. Rowson is in the same tradition, although the endpapers with their concealed skulls in a swirl of colour that looks like a biopsy are more flamboyant. Rowson slips in a final gag in the Acknowledgments, where he thanks “Old Grimmy” – “who is frankly a piece of sh*t but if I don’t say thank you properly our inevitable rendezvous might well be brought forward”. There are always “comedy books” at Christmas, usually frolicsome. What sets Rowson apart is that although I laughed, although I annoyed friends by reading bits of it out giggling, on reflection, my laughter rang somewhat hollow. Stuart Kelly

The Dance Of Death: A Vanitas, by Martin Rowson, SelfMadeHero, £9.99