Book review: Stevenson in Samoa, Joseph Farrell

Most of his friends were dismayed when Robert Louis Stevenson settled in Samoa after two years of sailing throughout the South Pacific. They weren’t only deprived of his company. They thought he was on a wrong course. When he involved himself in the confused politics of the islands, wrote letters to the Times criticising the imperialism of Germany, Britain and America, the three countries competing for mastery there, and embarked on a book about Samoan history, culture and politics, they were sure he was wasting his time and talent.

It is the first great merit of Joseph Farrell’s book that he shows why Stevenson became so involved and was right to do so. His own examination of the complicated politics of the islands is thorough and admirable; he makes clear what in most biographies of Stevenson has remained murky. Stevenson was no liberal – he detested Gladstone, himself a critic of imperialism. He was conservative and a Tory. But the commercial rapacity and political unscrupulousness of the three powers disgusted him and provoked his angry scorn. He saw, in what was being done to the Samoans, a parallel with the pacification, and subsequent depopulation, of the Highlands after Culloden. He was also critical of the activities of missionaries, though friendly with some of them. Perhaps he was wrong here; Farrell points out that 99 per cent of Samoans are now Christians. Stevenson himself was what Farrell calls a “lapsed Calvinist”, strong in disapproval of sexual immorality.

Advertisement

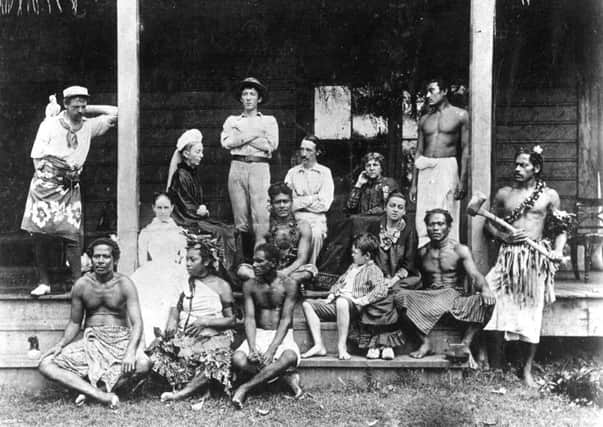

Hide AdThe first half of the book deals mostly with Samoan culture and the politics that held Stevenson’s attention. It is full of interest and repays the close attention it demands. Many readers will be more interested in the second half which tells of domestic life at Vailima and the books Stevenson wrote there (including the several he didn’t finish). Stevenson himself recognised that in establishing his paternalist estate there he was imitating Walter Scott; indeed, in self-mockery, he called his Abbotsford “sub-Priorsford”.

Stevenson’s marriage has always fascinated and puzzled his biographers. Many have taken against his wife Fanny and her children who, as they think, sponged on Stevenson. That Fanny, ten years older than RLS, was a difficult woman is not in doubt. She was temperamental jealous, possessive and demanding. They quarrelled often and sometimes bitterly. But the bond between them, if sometimes frayed, was never broken. Stevenson knew how much he owed to her, and even when exasperated by her behaviour, continued to love her. Farrell is more generous to Fanny than most other biographers, I think fairly.

Stevenson’s friends were mistaken in fearing that his preoccupation with Samoan politics would divert him from novel-writing. On the contrary: the Vailima years were arguably the most productive of his too short life. He wrote Catriona, the sequel to Kidnapped. I think it a masterpiece; Farrell is more doubtful, saying that the relationship between David Balfour and Catriona “is recounted from within the frame of Victorian decorum”. This is arguable; I find David’s hesitations and misapprehensions entirely credible, likewise Catriona’s puzzled and resentful reaction. A difficult relationship is, to my mind, subtly developed. Stevenson developed as a writer in Samoa, capable of writing The Eb-Tide which is darker and grimmer than anything of which he had previously been capable, and, in collaboration with his much-loved stepson Lloyd Osborne, The Wrecker and the wonderfully comic novel, The Wrong Box. In Samoa, Graham Greene wrote, “his fine dandified talent began to shed its disguising graces, the granite to show through”. Finally, there was Weir of Hermiston, so marvellous that his admiring and most perceptive friend Henry James wondered if he could have kept it up. “Among prose fragments,” he wrote, “it stands quite alone”.

Stevenson left Edinburgh, though Edinburgh never left him. Yet in one important respect, he outgrew Edinburgh in his Samoan years, shedding that note of “what a good Edinburgh boy I am” which disfigures some of his early essays, making, for instance, his treatment of Burns and Villon, neither of whom had the good fortune to be reared in Heriot Row, so unattractive.

I should say that Joseph Farrell had been a friend of mine for many years. I have one rule about reviewing books by friends; don’t, unless it is a good book which you can praise with honesty. I have no hesitation here. Stevenson in Samoa is very good indeed.

Stevenson in Samoa is published by MacLehose Press, £18.99