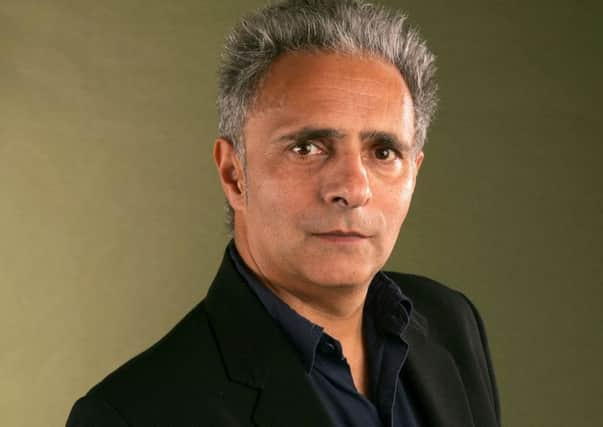

Book review: The Nothing, by Hanif Kureishi

One might say that The Nothing is Hanif Kureishi’s Philip Roth novel, a book in which we are trapped within the mind of an old man confined to a wheelchair, frustrated, angry, resentful, suspicious and still obsessed with sex, even when he no longer has control of his bodily functions.

The reader’s relationship with the narrator may also be resentful. Waldo, a famous filmmaker, addressed by many as “maestro,” is a singularly unpleasant old man and what used to be called a “dirty-minded” one. Of course there is no reason why novelists should choose to write about agreeable characters, none either why repulsive ones can’t be compelling. Indeed for the author it’s an interesting challenge, one that Kureishi meets boldly, usually interestingly, sometimes wittily.

Advertisement

Hide AdNevertheless, for all his skill, reading The Nothing is a bit like being cornered by an old man who insists on telling you at length about his troubled life, and you find you can’t slip away. At 167 pages it’s only a novella but feels like a rather long, too long, novel.

Waldo insists he loves his much younger wife, Zee, who cares for him with what appears to be devotion. He recalls their sexual history and relates the fantasies in which he still indulges. He remembers that Zee “once said she’d love me even if I didn’t have a penis. Did I believe that for a moment? Who doesn’t love cock?”

The way he talks and thinks reminds me of a story told by Claudio Magri about James Joyce and the great Trieste novelist Italo Svevo. Joyce was shocked when Svevo used a coarse anatomical word in conversation. Such words for the author of Ulysses could properly be written but not spoken. For Svevo it was the other way round; he wouldn’t have used the word he had just uttered.

Waldo has no such inhibitions; nor, it may be, has Kureishi. The discriminating reader may be on Svevo’s side. It may be natural for an old man whose body is decaying and near dissolution still to entertain sexual fantasies, but he should keep them to himself. Anything else is embarrassing; and that’s a word that can fairly be applied to this book.

Waldo becomes convinced that Zee is having an affair with a man, part friend, part hanger-on, called Eddie. He despises Eddie as a failure, a dabbler and sycophant, for years on the fringe of the film world, a third-rater, deep in debt, with broken marriages behind him. It makes it worse that Eddie reveres him and shows himself to be kind and helpful. It’s intolerable to lie in bed and imagine their coupling, eavesdropping on it, or pointing his video camera at the pair. He is at once tormented and excited by his suspicion. To prove it he even eggs them on, facilitates their affair, wills his wife’s infidelity, all the while plotting ways to have his revenge and destroy the wretched Eddie.

He’s demented of course, but still insists that he is justified. He had never treated people well, especially those weaker than himself. Why should he act differently now?

Advertisement

Hide AdKureishi inhabits Waldo with uncommon understanding, and I expect he delighted in his creation. He gives us conversations between Zee and Eddie, and, though it is not clear whether Waldo actually overhears them or merely imagines them, one has the impression that Kureishi expects the reader to sympathise with the lascivious and jealous old schemer.

I have to say that I failed to do so. My sympathies were with the abused Eddie and Zee, both of them, for all their weaknesses, better people than Waldo. I would have understood it if she had placed a pillow over the old lecher’s face and pressed down hard.

Advertisement

Hide AdThis response, itself immoral, does at least suggest that Kureishi has written a novella that poses interesting and even important moral questions, in this like Philip Roth.

The trouble, as with some of Roth’s novels, is that Kureishi makes irritating demands of the reader. Writing in the first person he is on Waldo’s side. Usually it is hard not to feel sympathy for a first-person narrator. Not this time.

The Nothing is published by Faber & Faber, £14.99