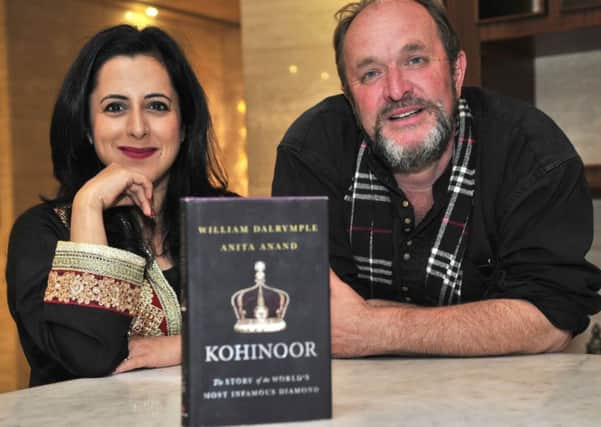

Book review: Koh-i-Noor, by William Dalrymple & Anita Anand

The subtitle of this fascinating book calls the Koh-i-Noor “the most infamous diamond in the world”. It is now of course lodged in the Tower of London as one of the Crown Jewels, and is likely to remain there, despite repeated but competing demands from the Governments of India and Pakistan for its return. It came to Britain after the army of the East India Company annexed the Sikh state of the Punjab after the second Anglo-Sikh War in 1846, and in effect deposed the ten-year-old king Duleep Singh, compelling him to sign a Treaty, one clause of which provided for the handover of the diamond to Queen Victoria. It was a shabby business, forced by the British commander, the Earl of Dalhousie, though it should be said the Sikh kingdom was already in chaos after three heirs of the great Ranjit Singh had been assassinated.

The book is in two parts. The first is written by William Dalrymple, who has made himself our leading authority on 18th and 19th century India, and it covers the turbulent history of the Koh-i-Noor from the time when the Persian Nader Shah, a brilliant and brutal soldier, humiliated the Mughal Emperor, sacked Delhi and seized the diamond, the Peacock throne and other jewels. After he was murdered, it was taken by the Afghan king, at a time when the Afghan court was a centre of high civilisation. Turmoil there was exploited by the Sikhs, Afghanistan collapsed, and the beneficiary was Ranjit Singh.

Advertisement

Hide AdDalrymple tells this complicated story with verve and admirable brevity, drawing on a wide range of literature and memoirs. He paints a picture in which elegance and refinement are married to treachery and hideous brutality. There is no shortage of horrors: torture, blinding of captives and a grisly, revolting account by a Hungarian doctor of Ranjit Singh’s funeral, at which the dead king’s wives were compelled to commit “suttee” – that is, being driven or thrown still alive onto their late husband’s funeral pyre – a practice later made illegal by the British Government of India.

Readers might like a few more dates to help them keep track of the twists and turns of the narrative, and Dalrymple’s publishers might have served him better by providing more than a single, not very clear map.

Dalrymple is a lover of India and Indian history and no great admirer of the British Raj, certainly not an uncritical one. But two things are clear. First, however unscrupulous and violent the British conquest and annexation of India may have been, it never came close to matching the viciousness and cruelty of the highly civilised, art-and-poetry-loving native rulers. Second, possession of the Koh-i-Noor itself has always been won by the sword and the gun. Nobody, it may be said, has a just title to it.

Anita Anand continues the story, relating the circumstances of the jewel’s arrival in Britain where it was put on public show at the Great Exhibition of 1851, at first to general disappointment. She also gives us the ultimately sad story of the boy-king Duleep Singh himself. Removed from the care of his mother (who was deemed politically dangerous) he was lucky to find an affectionate guardian in John Login, a Scottish doctor, later knighted. The boy converted to Christianity, apparently of his own volition, and in his teens came to be educated further in England. He became a favourite of Queen Victoria, who was, unlike most of her British subjects, entirely free from racial prejudice, and was brought up with the royal children. As an adult, however, he quite naturally came to feel resentful, as exiled monarchs usually do, began to drink heavily (like his grandfather Ranjit Singh), was wildly extravagant and a sore financial burden to the India Office, which was perhaps just what it deserved. This is a book which anyone interested in 19th century India and Indio-British relations will want to read. There’s also a great deal of information about the diamond itself and other jewels, though this is of more specialised interest, and is indeed likely to bore anyone who, like me, doesn’t understand some people’s fascination with precious stones.

Koh-i-Noor is published by Bloomsbury, £16.99