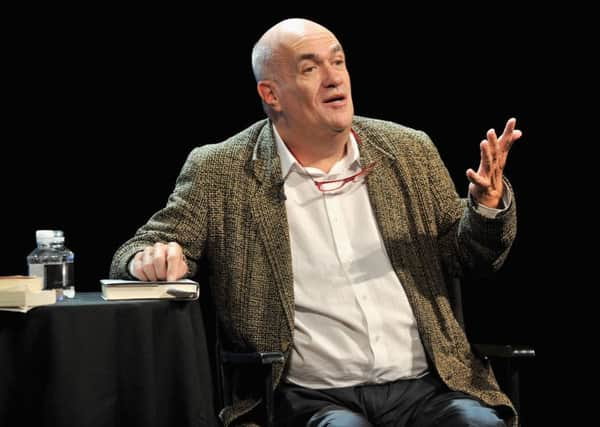

Book review: House of Names, by Colm TóibÃn

We always come back to the Greeks. The horrors of the House of Atreus were given their first classic expression in Aeschylus’ trilogy Oresteia, reprised by Sophocles and Euripides, and have been the subject-matters of paintings, poems, dramas and novels ever since, one good recent one being Barry Unsworth’s The Song of the Kings which, however, tells only part of the story. Now Colm Tóibín gives us his version of it all.

The outline may be given briefly.The Greek fleet on the way to the siege of Troy found itself becalmed.The goddess Artemis decreed that the wind would change only if Agamemnon, the Greek commander-in-chief, sacrificed his daughter Iphigenia. At the insistence of the Army, Agamemnon obeyed the goddess. Ten years later, on his triumphant return from Troy, he was murdered by his wife Clytemnestra, with the assistance of her lover, Aegisthus. The surviving children, daughter Electra and son Orestes, vowed or were obliged to avenge their father. For murdering his mother, Orestes, who as a boy had been carried away from the palace, was, in some versions compelled to be a wanderer on the earth.

Advertisement

Hide AdTóibín tells the terrible story in three voices. The first is Clytemnestra’s and is entirely convincing, and the second, less so, is Electra’s. Orestes’ story is told in the third person. Much of it covers his wanderings after he was taken and removed from Mycenae with other noble youths by order of Aegisthus and the connivance of Clytemnestra. The story is so dramatic and the crimes so awful that it is hard to go far wrong, and for the most part Tóibín’s version is gripping. Hatred simmers. Fear stalks the corridors of the palace and the stench of blood is pervasive. Clytemnestra’s description of the sacrifice of her daughter and the contempt and loathing she feels for her husband is brilliant; one understands why she determined to kill him and nursed the idea of revenge for so long. Her impatience as she has to endure the returned hero’s triumphant boasting as she waits to get him into the palace to meet the death she has prepared for him is utterly convincing, and chilling. It couldn’t have been better done.

Was the murder and all that followed from it justified? This was a question that occupied and perplexed the Greek tragedians. In consenting – reluctantly? – to his daughter’s appalling death, Agamemnon was not only bowing to the demands of his army; he was obeying the gods. Was a man who did as the gods demanded to be held responsible for what in human terms was a crime? The difficulty for a modern author is how to make this obedience credible. Tóibín manages it, if only just, by showing Agamemnon distracting himself by engaging in sword-play with his young son, Orestes, action Clytemnestra condemns as cowardly.

Then if Clytemnestra was justified in murdering her husband, was Orestes likewise justified in avenging his death, and with the connivance of his mourning sister Electra, killing his mother so many years later? Tóibín wisely offers no judgement, but he knows that crimes have consequences and the ending is ironic, for he has Orestes, in company with his friend Leander, companion in his childhood exile, reflecting that “in time what had happened would haunt no one and belong to no one, once they themselves had passed on into the darkness and into the abiding shadows”. Not so, not so.

The sacrifice of the innocent Iphigenia and the murder of Agamemnon bred horrors, and Tóibín deals well with the consequences: political upheaval, civil war, executions, disappearances, everything that we would now recognise as characteristic of a failed state. The enduring strength of the myth is that it is true for other times, other places, other cultures. Orestes and Macbeth or Hamlet are blood-brothers. Steeped in blood, for all the characters, there is no turning-back. So universal is the myth that it matters little that there is very little sense of Greece in the novel, Orestes’ boyhood wanderings being set in a wilderness that might be anywhere.Having set the tragedy in motion, the gods withdraw, leaving men and women caught, fearful, confused and bitter, to dree their weird.

House of Names is published by Viking, £14.99