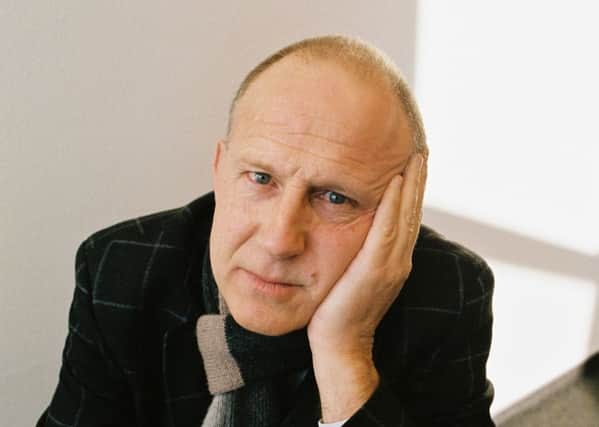

Book review: In Extremis, by Tim Parks

Parks is a wordy writer, not given to economy. The novel is narrated by Thomas, a 59 year-old professor of Linguistics, summoned from a conference in Amsterdam by an email from his sister telling him their mother is in a hospice on the point of death. Thomas himself is confused, garrulous and guilty; also a sufferer from Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. There is a lot about his urinary problems, too much, I would think, for many readers; but they can always skip these passages.

His mother is, or has been, a devout Christian, widow of a Low Church clergyman. Thomas and his brother are non-believers; their sister shares their parents’ faith, unquestioningly. Thomas is separated from his wife, though remains close to their children, and now has a much younger girlfriend in Madrid. There is a sub-plot featuring his closest friends David and Deborah. David is a philanderer. Their son Charlie, who may or may not be gay, has just broken a chair over his father’s head and may be prosecuted for assault. It is not clear why Charlie did this. Deborah is puzzled. She believes Charlie will speak to Thomas and brings him to the hospice where Thomas is waiting for his mother to die and pondering the things he has done which he ought not to have done and those he has left undone which he ought to have done. Charlie won’t explain himself, or can’t, until he tells Thomas he has read the emails he exchanged with David. There is a lot of emailing in the novel. Thomas sometimes seems to communicate more easily through his computer than face-to-face.

Advertisement

Hide AdParks admirably explores emotional complexity. In his own mind Thomas is a mess; to the world and his own family he is a success. He loved his mother, but for a long time hasn’t been easy with her. There is too much he hasn’t been able to say, not even able to tell her that he left his wife four years ago. He thought she would disapprove, and he hates to be the object of disapproval; it will surprise him to learn that he didn’t know her well enough, not certainly as well as he thought he did. But Thomas, whose subject is the way language changes and who is alert to what this reveals about the way people make a new reality, is emotionally an evasionist. He recognises this himself, and despises himself for it. Yet he is also aware that this isn’t how his family and friends see him. They think him reliable and efficient. He resents his mother’s Christian certainties and yet envies her self-assurance.

Parks is good on detail, good on hurried meals in bad restaurants, good on weather – always important in a novel. The other family members, including Thomas’s four children, are brought effectively to life. So is the hospice and the pain and frustration of watching someone you have loved die, and wishing the waiting was over, while everything else in life is held in suspension. There is, happily, comedy too: a self-confident brother-in-law who can talk only of his dogs and the photographs he obsessively takes of them, a High Church clergyman whose complacency irritates Thomas and his brother who has flown in from California.

Parks has a remarkable talent for presenting the waywardness of thought. When the ghastly clergyman drones on about “the Lord Jesus Christ, who shall change our vile body that it may be like to His glorious body”, Thomas thinks of his Spanish girlfriend whose “body, in particular, was not vile at all”. The clergyman insists that the mother’s death was beautiful; Thomas thinks she “smells of cancer”. Faith stumbles against physical realities and, as far as Thomas is concerned, loses badly.

Good fiction makes you think and feel at the same time. This novel does that very well, at times comically, at times distressingly. There is hustle and bustle, but the most fully realised character is the mother slipping away from life, disturbingly present in memory.

In Extremis by Tim Parks, Harvill Secker, £16.99