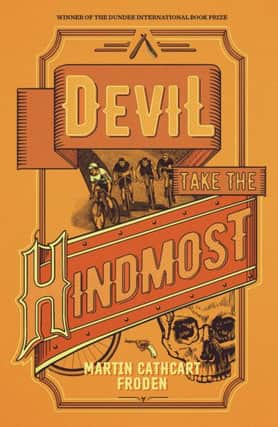

Book review: The Devil Take the Hindmost by Martin Cathcart Froden

The Devil Take the Hindmost by Martin Cathcart Froden | Freight, 317pp, £9.99

Martin Cathcart Froden, born a Swede, now by adoption a Glaswegian, won last year’s Dundee International Prize for a debut novel with this book. The setting is London, the theme drug-fuelled velodrome racing, and the milieu criminal. The publishers invite comparison with Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock, now an established classic. Greene described that novel as an “Entertainment”, though with its themes of mortal sin and salvation set against ordinary human morality, it is more than that. Yet its seedy glamour is certainly entertaining, in a broad sense of the word, and Froden catches something of the same mood.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe plot is rambling, flying free of credibility. Paul, a big Scots laddie, escaping the family farm after a quarrel with his father, heads for London with his prized racing bike. An innocent in the Big City, he falls among thieves and scoundrels, one of whom, Silas, a loan shark and criminal, not only sees the young man’s potential but also falls for him. Paul, however, is the innocent abroad, though he will prove resourceful. Silas introduces him to the world of velodrome racing, and Paul soon makes his name once he accepts the need to pep himself up with amphetamines. Meanwhile he dashes about London, delivering letters and collecting bets for a nasty criminal Mr Big by name of Morton.

There is a good deal of repetition – unavoidable in accounts of Velodrome races, though Froden might have learned from Dick Francis who in his horse-racing novels rationed the number of steeplechases described in detail. There is also love-interest of a somewhat dangerous sort, and the novel, quickening its pace in the later stages, speeds to a violent and bloody conclusion. With a bit of willing suspension of disbelief, the end is agreeably satisfying.

The novel is written partly in the third person, partly in other voices, the transition being well done. Froden is also adept at modulating the pace, giving us moments of stillness – conversation between Paul and the girl he is falling in love with – to balance the scenes of violence. Froden has also taken an unusual subject and this makes his novel pleasantly different from the common run of thrillers today, although it is too long and would have benefitted from some severe cutting.

Its weaknesses are as evident as its strengths. Though it is set in London in the 1920s there is little real sense of either place or time. I would say that Froden’s criminal underworld is wholly imaginary – unlike Greene’s in Brighton Rock (since this comparison has been forced on the reader). Morton, the chief villain, is authentic only in the sense that like the villains of run-of-the-mill Twenties thrillers he is an utterly improbable criminal mastermind. Compare him, for instance, to William McIlvanney’s hard man, John Rhodes, and you see that his menace stays on the page, doesn’t enter the reader’s imagination.

Nevertheless there is more here, considerably more, to enjoy than to criticise. Froden has a keen eye for detail and an ability to convey shifting moods and emotions. Paul is a convincing hero-innocent (though I couldn’t quite believe in him as a Scots farm-boy) and his shifting relationship with Silas is nicely developed. I’m not surprised that the novel won the Dundee Prize. I will be surprised if Froden doesn’t write better ones which win other prizes.