Book review: Deaths of the Poets, by Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts

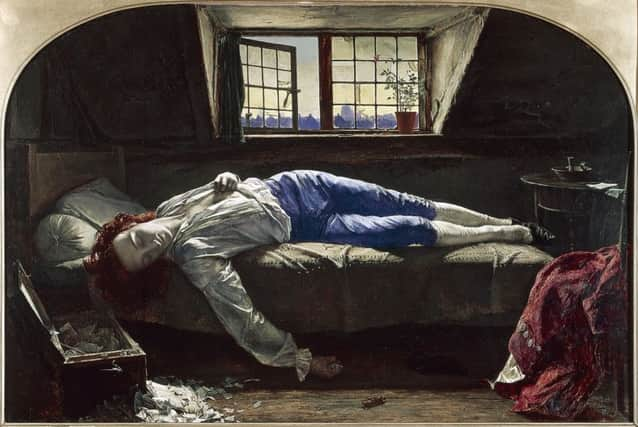

They begin with one of the most iconic images of the death of the poet; Henry Wallis’s Pre-Raphaelite The Death Of Chatterton, painted 86 years after the “marvellous boy”, astonishing poet and wee chancer died. As an icon of artistic expiration it both harks back to the Romantic generation of Shelley, Keats and Byron and projects forward towards the self-destructive Winehouse, Cobain and Morrison (I know, none of them are poets, but as Roberts and Farley confess, the rockers have rather usurped the writers). How has the image of this idealised youth, a butterfly broken on a wheel, become a synecdoche for a particular view of the artistic career? And is it even a career?

So chapters alternate and contrast the long-lived and the taken-too-soon, those who outlive the point where they feel they should have died and those who didn’t even expect to when they did. It is a little primer in some wonderful poets, and the authors manage to contrast the obvious (Marianne Moore, Sylvia Plath, Philip Larkin, RS and Dylan Thomas) with the regrettably more esoteric (John Riley, David Jones, Keith Douglas, Rosemary Tonks, John Berryman – I find it bizarre that Berryman is still a best-kept secret). It would be easy to pull an old reviewer’s trick and bemoan “But why no Burns? Why not include Poe, not just for his profound grasp of prosody, but not least for the toothsome legend of the Poe Grave Visitor?” They have chosen whom they have chosen, and have written about them with gravity and levity, combining acute analysis of the poetry with close attention to the myths we build around poets which are so eczematous they inflict craquelure on every reading thereafter – who could read Weldon Kees now without the weird disappearance retro-engineering each poem? Pope said that poetry was “What oft was thought but ne’er so well express’d”, and when you read a description like “young mothers with buggies equipped for polar exploration, two elderly women who seem to be engaged in synchronised pasty-eating”, it’s hard not to disagree.

Advertisement

Hide AdBut I am going to talk about omissions. I shall because the final chapter presents two poets – WH Auden and Robert Frost – as anomalies in their researches. Frost was conservative but radical, lauded but snipingly private, a plain-spun who ate cordon bleu; Auden ought to have been a young death – the Benzedrine, cigarettes, and vodka martinis diet is not recommended – but knocked out a respectable 66 for one, even predicting his own death: “I shall probably die at midnight, in a hotel, to the great annoyance of the management.” Auden and Frost are truly wonderful poets, but their dictions – formal but free, vernacular but vatic, ironic but awry, modern but modest – are the three-chord song of contemporary poetry. The book’s absence is about a kind of poetical difficulty, best described as “The Short Nineteenth Century”. This book is not in any way a literary history, and its virtues are that it is not, but why are Tennyson, the Brownings Robert and Elizabeth, Swinburne, Arnold, Clough, Rossetti (Christina, not Dante Gabriel) not part of the story the authors are telling? There are poetries which are lush and knotty, precise and nebulous, lives which were drastic and dramatic, inextricable and private. The omission tells us nothing about the book – and a good, clever, kindly and enjoyable book it is, like eavesdropping on two smarter friends when they are sparking off each other – but the hiatus is odd. Any book with such a title is asking questions about genealogy: whence these poets? whither them? In a way, it’s a book of elective ancestors, and the 19th century is the mad uncle buried under the woodpile.

Farley and Roberts are always entertaining and illuminating, gentle guides and quixotic questers. As they realise, the reason they are looking for the deaths of poets, and not novelists, artists, physicists, or waste disposal operators is that poetry has always been obsessed with death, and each poem, with its lines not reaching the edge and its ending not reaching the page, is a little death and a perfect tomb.

*Deaths Of The Poets, by Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts, Jonathan Cape, £14.99