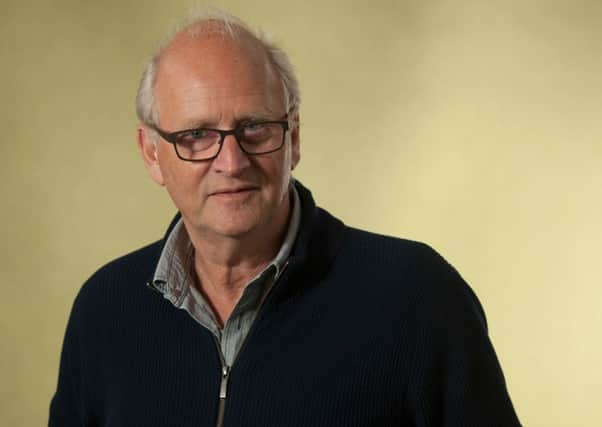

Book review: Dear Mr M by Herman Koch

Dear Mr M by Herman Koch | Picador, 443pp, £14.99

Mr M is a famous writer, less successful in late middle-age than he used to be, nevertheless still well thought of, not least by himself. Now he is being watched, stalked indeed, by a neighbour who narrates part of this novel. The narrator has a grudge against him, rooted in Mr M’s most successful novel, Payback – the story, drawn from newspapers, of the apparent murder of a High School teacher by two of his pupils, a boy and a girl. It is soon clear that the stalker’s resentment has been provoked by the novelist’s readiness to appropriate the lives of others and use them to his advantage.

This is an interesting question, and one understands why it has attracted Herman Koch. Novelists are magpies, which is to say thieves, some more blatant than others. Are you entitled to use family, friends, acquaintances or even people whom you know of only through reports in the media as material for fiction? And what if you get them wrong? Aren’t they entitled to object? Even to seek their own revenge?

Advertisement

Hide AdSo the germ of the novel is interesting. But a novel may have an interesting theme while, sadly, being quite often dull, with tedious passages; and this is the case with Dear Mr M. The stalker is a bore and so most of the time is Mr M himself. I found myself wondering if he was based on a rival novelist known for his adept cultivation of the media; then if the pompous and jealous Mr M, so carefully self-protective, wasn’t perhaps an expression of the author’s self-disgust. He may be neither of these things of course. What matters is that the Mr M chapters – a book-signing in a library, an interview with a celebrity journalist – are all too drearily true to life. Each might have been effective if cut heavily. Each makes its point quickly and then repeats it again and again.

This is disappointing, all the more so because other parts of the novel – those which deal with the real story behind Mr M’s bestseller Payback, later successfully filmed – are very good indeed. There is an account of a weekend spent by the group of High School children in the holiday house belonging to the girl Laura’s parents, which crackles with life. Laura is the class beauty, who with her boyfriend Herman, a skinny youth with a cine camera, will be accused of the teacher’s murder.The teacher has seduced her, not without encouragement. Herman, highly intelligent, socially awkward, child of a marriage in cold, slow-motion dissolution, is brilliantly drawn, utterly convincing. There is a nice paradox here. Herman, adept in recording defining moments of social experience on camera, himself invades other people’s privacy, fixing them forever in what might be only momentary poses. He is as much a thief as the novelist who will take possession of Herman’s and Laura’s story for his own purposes, and advance his career by doing so. What then is the difference between Herman and Mr M? Will Herman become his stalker only because his version of the story is not Mr M’s? That said, the transition of Herman from engaging, if difficult , schoolboy to obsessed adult is too abrupt. It doesn’t, as presented, quite ring true.

One often wonders about the relationship of a novelist to his characters. If you are tempted to identify the author with Mr M, you may find yourself asking why he should also have given his own Christian name to the boy Mr M portrays as a killer. In general novelists don’t give their own name to a character unless, like Isherwood in Goodbye to Berlin and Down There on a Visit, they are writing scarcely veiled autobiography and are happy to be identified with the narrator.Certainly it doesn’t happen by chance.

An odd novel, then, a curate’s egg of one, in which parts are excellent and parts anything but. I found myself now intrigued, now bored, sometimes delighted, sometimes irritated. Nevertheless, it’s worth reading, an example of the flawed novel which by inviting reflection is ultimately, perhaps to the reader’s surprise, more interesting than less ambitious assured successes.

• Herman Koch, Edinburgh International Book Festival, 29 August