Book reviews: Words Onscreen | The Whites

Words Onscreen

Naomi S Baron

Oxford University Press, £25

THERE is an urban legend about an infant being given a book and looking perplexed when nothing happened as their finger swiped over the page. Whether or not it is actually true, it taps into anxieties we have about the digital natives who will click rather than turn, browse rather than dwell, and download rather than treasure.

I’ve never been certain such fits of the conniptions are wholly justified. All my nephews have understood the technology we call “the book” since before they could speak, and part of that, I’m sure, is due to such innovative, tactile and happily haptic titles as That’s Not My Dinosaur. But Naomi Baron has, at the very least, started a proper academic investigation into whether or not reading is fundamentally different if it is done on screen or on paper. Her subtitle indicates her conclusions: “The Fate Of Reading In The Digital Future”. The fate, not the future. We’re, as Private Frazer used to say, doomed.

Advertisement

Hide AdTo be fair, this is one of the few books to address the question without resort to such clichés as “I can’t smell an ebook”. Although her samples are small, they are telling. The results seem to indicate that there is a profound and different cerebral experience if one is reading War And Peace on a mobile, iPad or laptop, or on some pulped trees.

Put simply, she concludes that paper encourages us to read deeply and the screen encourages us to read broadly. It is easier to skim, to data-graze, to Ctrl-F a quote on the screen. These are not insignificant advantages, but they rely, for proper use, on the reader having had the deep experience of reading in an older form. I remember at one point being curious about the idea that Jasper in Charles Dickens’ unfinished The Mystery Of Edwin Drood, might be linked to Thuggee cults. Project Gutenberg allowed me to find, quickly, all the references to silk, knots, necks and ties in that work – far more swiftly than had I had to re-read the book. But I had to know what I was looking for first; a memory that only reading attentively and with consideration would allow. E-reading is a wonderful supplement, but not a replacement.

The book, Baron argues, lacks distractions. If I am bored with Pierre Bezukhov’s conviction that Napoleon is the Antichrist, I can’t use my Penguin Classic of War And Peace to play Candy Crush instead. In terms of pedagogy, the students Baron interviewed would prefer a paper book to an e-book, if they were the same cost, and frequently referred to highlighting, writing marginal comments and a different kind of remembering (that quote is on the bottom half of the right hand page about two-thirds of the way through). This could have been pushed further. Perhaps the most startling statistic in her work is that an online trawl over student papers revealed that citations to articles tended to be from the first page of the piece – a grab-quote, rather than a measured interaction with the criticism. As she wryly, notes, we are in the realm of “tl;dr” – “too long; didn’t read”.

The ebook is more akin to the scroll than the codex; hence the variously inept attempts at making a “flickable” ebook. Of course, one can annotate ebooks, but the annotations become the property of the publisher. As Baron rightly notes, an ebook is not a possession, it is a permit to read. You don’t own an ebook, as anyone who “bought” George Orwell’s 1984 in an unlicensed edition from Amazon knows to their cost. Overnight the corporation deleted the text from their devices. #ironyfail.

Baron, maybe, tries to take on too many targets. Goodreads and hyper-reading, educational policy in California and texting in Tokyo – a more tightly focused book might have been more persuasive. The idea of a genuine “ebook” – a narrative that could only exist in an online form – is hinted at, but not explored.

With short, choppy chapters and sub-chapters, this reads more like an internal academic document than a fully realised argument, and when it becomes polemical it strays into mere hectoring. Yet this does begin a proper debate about the future of reading, even if reading it is chore-ish. It is a book that, oddly, I would prefer as an ebook, to take from it what I need and when, rather than a volume to sit next to Eco, Manguel and Burgess on bibliophilia.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe book, we should not forget, is a relatively recent phenomenon. It took some time for Gutenberg’s moveable type to settle into the form we now have, with such overlooked innovations as page numbers and copyright. Reading, however, has been around for far longer, and I’m sure there were Mesopotamians who thought papyrus was a dastardly fad compared with good old clay. People may be reading differently online, but the option to read deeply on the page still exists. The digital dystopia is not here yet. STUART KELLY

The Whites

Harry Brandt

Bloomsbury, £12.99

THE name may be unfamiliar but the chances are, if you’re reading this review, you will know of Harry Brandt’s previous work. His real name is Richard Price, whose award-winning novel, Clockers, was filmed by Spike Lee. His screenwriting credits include The Color Of Money, Sea Of Love, and helping David Simon write later episodes of The Wire.

Advertisement

Hide AdDespite the name-change, The Whites, a devastating depiction of crime and punishment, mines a similar seam to its predecessors. More importantly, it is just as good – if not better.

The title is cop-speak for the ones who got away, crooks who proved impossible to convict. Now someone is bumping them off one by one.

The stereophonic narrative is shared by two serving officers: family man Billy Graves and fruit-loop Milton Ramos, who still holds Billy’s wife, Carmen, responsible for the death of his mother and two brothers.

He has a point: as a spiteful teen she said something that ended up blighting both their lives. Now Milton, overwhelmed by “loss and loss and loss”, is out for revenge.

As Milton plays cat and mouse with his unsuspecting colleague – first targeting Billy’s sons then his father, an ex-cop succumbing to dementia – his, and our, blood pressure soars. And yet Brandt still makes us feel for the evil Milton, “galled to the edge of his teeth by the divide between the grief givers and the grief takers”. Billy is by no means a saint, either. His lies once scuppered the promising career of a female journalist. It is payback time all round – especially when he suspects that the killer of the Whites lies close to him.

The wealth of freakish incident encountered by the cops is reminiscent of Joseph Wambaugh’s Hollywood series of police procedurals. Throughout, the culprits are referred to as “actors” not “malefactors”. However, the result, while equally gripping, is less flippant, less sentimental. MARK SANDERSON

Advertisement

Hide AdGods And Kings: The Rise And Fall Of Alexander McQueen And John Galliano

Dana Thomas

Allen Lane, £25

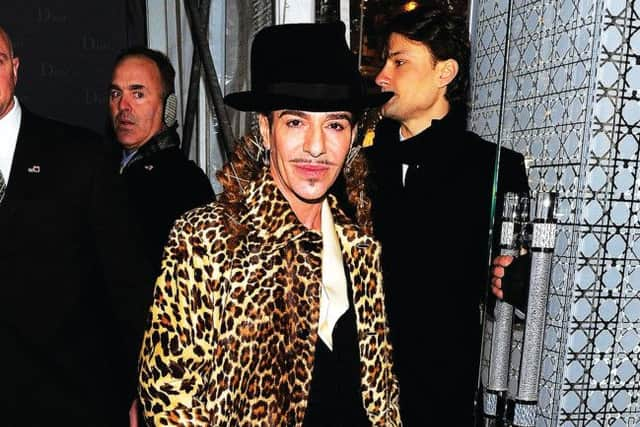

LAST month, the disgraced designer John Galliano returned to fashion with an haute couture collection in London for Maison Martin Margiela. The comeback was warmly received by the British fashion industry, which seemed relieved to welcome him back into the fold.

Advertisement

Hide AdGalliano will soon be joined, in spirit at least, by the late designer Alexander McQueen, who is to be honoured with an exhibition at the V&A in London. He was described as a “button-pushing marvel: ethereal and gross” and his retrospective seeks to plot his position as British fashion’s greatest visionary, while exemplifying the darkness that came to define both his catwalk presentations and his character.

This sombre, grotesque undercurrent inherent to both designers inspired American fashion journalist Dana Thomas to embark on a study of their simultaneous rise to stardom and self-destruction.

She begins with detailed accounts of Galliano the boy, a devout Catholic wandering the streets of Gibraltar, and of McQueen, the son of a cabbie and the last child of six raised in a “simple home” in Lewisham.

We follow Galliano as he transforms from the shy graduate wheeling his first collection on foot around London into the drug-addled Dior designer who, in 2011, was caught on camera spewing anti-Semitic hate. Accounts from former Galliano employees reveal how he flipped from conscientious boss to elusive drug addict, never able to tell his father he was gay.

Even more tragically, we learn how McQueen was raped as an 11-year-old and how the event came to define his character and inspire the darkest elements in his work.

Thomas conducted interviews with more than 100 of his friends, family and colleagues. Among the most revealing claims are that McQueen was HIV-positive and spent up to £600 on drugs a night. We learn of his sorrow following the suicide of his friend Isabella Blow and how, at his most paranoid, he would film himself in bed for fear of being raped by a ghost while he slept.

Advertisement

Hide AdThomas also describes McQueen and Galliano’s greatest catwalk achievements. We sit alongside LVMH boss Bernard Arnault as he heaps praise on Galliano following his debut collection for Christian Dior and join a panic-stricken McQueen in a cab as his press officer tries to coax him into a meeting that will transform his fashion label into a luxury giant.

Thomas, who has a habit of making sweeping generalisations for shock value, set out to tell the tales of two fashion revolutionaries brought down by contemporary culture and the industry they gave so much to. And she has. Yet as I read the details of the moment McQueen’s lifeless body was found swinging from a belt in his wardrobe, I was left wondering if she had to expose a man’s soul to do so.

KAREN DACRE